SIEU president Mary Kay Henry on essential jobs, organizing, and the future of work.

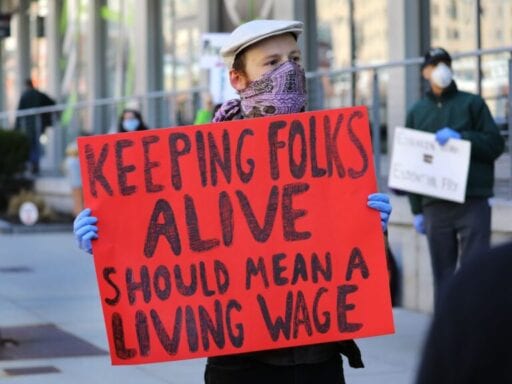

Grocery store clerks. Fast-food cashiers. Hospice care workers. Bus drivers. Farmworkers. Along with doctors and nurses, these are the people who are putting their own lives at risk to keep our society functioning day in and out amid the worst crisis of our lifetimes. We call them heroes, we label them “essential,” and we clap for their brave efforts — even though none of them signed up for this monumental task, and many of them lack basic health care, paid sick leave, a living wage, cultural respect, and dignified working conditions.

This conversation on The Ezra Klein Show asks: How did things get this way? Why did we end up with an economy that treats our most essential workers as disposable? And what does an alternative future of work look like?

Mary Kay Henry is the president of the Service Employees International Union, a 2-million-person organization that represents a huge segment of America’s essential workers. If you ask a traditional economist why essential workers are paid so little, they’ll talk about marginal productivity and returns to education; ask Kay Henry and she’ll talk about something very different: power.

A lightly edited excerpt from our conversation follows. The full conversation can be heard on The Ezra Klein Show.

Ezra Klein

What has it been like watching this unvalued work get reclassified as essential?

Mary Kay Henry

My first reaction to it was, finally people are beginning to understand how critical these jobs are to the functioning of a nursing home, the delivery of food in fast food, or kicking these checks out the door.

But then right behind that, as the clapping and the recognition went on, the number of stories where employers were refusing to follow basic CDC guidelines on health and safety and personal protective equipment — that’s the kind of disrespect and inhumane conditions that people are facing. I’m thrilled at the opening to have the conversation about the undervaluing of work and the need, if we’re going to call them essential jobs, to invest in them as if they were essential jobs.

Ezra Klein

Do you think we will? I worry that the reclassification of essential workers as “heroes” is a way of not having to economically value them because we are praising them.

Mary Kay Henry

I don’t think that change is going to happen by accident or simply because of the pandemic. I think that change in the value of this work is going to happen because working people are standing up and demanding what they need to be safe. People are fed up in a way that I have never seen in my lifetime. I think workers are going to be unwilling to accept anything less than real change in the value of their work and structural change in the economy that transforms these jobs once and for all into jobs that are valued by society, but also jobs that people can live on and provide a decent life for their families.

Ezra Klein

In your view of the economy, how does a job get valued, at least in “normal” times? Why are some jobs valued highly and others aren’t?

Mary Kay Henry

I think it gets decided by the interaction between corporate power and who is elected in government. In other countries around the world, government puts a check on corporate power and workers have a seat at the table to make sure they lead a decent life. Fast-food workers in every other [Western] country are getting 80 to 90 percent of their income replaced as they were sent home because of the pandemic. They have health care. They have paid time off.

But in this country, Diana Alvarez, a single mom in Chicago, had her 40-hour-week cut to eight hours at the beginning of the spread of the pandemic. And Chicago had no paid sick leave. Now she’s trying to pick up other shifts at other stores. That’s a decision that the multinational corporation of McDonald’s makes to play by the rules that have been rigged in this system long before Covid.

I think the devaluation of care work was a decision back in the ‘30s when we were trying to pass Social Security, the Fair Labor Standards Act, the National Labor Relations Act. Home care workers, domestic workers, and farmworkers were all written out of the act as a compromise between northern and southern legislators who didn’t want black and brown workers covered by any laws. And because those workers had no rights under the law, their wages fell further and further behind because they couldn’t join together and bargain a better life. So there are historic reasons.

And then there’s a system where our politics has favored corporations who supposedly were going to create good jobs for us, and that’s how we were all going to thrive. It’s crystal clear that this trickle-down theory is long past. We have to have an economy where we have elected officials standing with workers to hold corporations accountable to investing in their frontline workforce.

Ezra Klein

Tell me a bit about the story of how this was done in the 20th century with manufacturing work. Manufacturing jobs became good jobs — they didn’t start out that way. They didn’t start out well-paid. They didn’t start safe.

But they became dignified both in real terms of money and our national mythology. How did that happen?

Mary Kay Henry

Workers joined together and sat down in Flint and said, we’re not working anymore until we get paid enough to feed our families. These workers catalyzed strikes all across steel, auto and rubber, which were the dominant industries in that generation. And companies made a decision in order to be able to produce their products to recognize the union and bargain a contract. That got codified in law mostly as a way to stop worker disruptions and strikes. Labor law didn’t encourage organizing of workers — it contained it in the ‘30s.

I think that’s what’s so hopeful about this moment. Long before Covid we were seeing “Red for Ed” strikes, 60 percent of Google workers walking off the job one day to create a global statement about what they expected from Google, Uber and Lyft drivers, and Amazon workers in the midst of Covid walking off the job. Those are all disruptions that I think in this moment are going to move to another scale, because now basic health and safety protections aren’t being followed. People aren’t willing to tolerate being so disrespected as being willing to have their lives sacrificed.

And it’s sparking a new level of workers’ brave decisions to disrupt the operation and get employers like Domino’s after those workers. In California, Domino’s workers kept repeatedly striking and they got the personal protective equipment and paid sick [leave]. Those are examples to me of how when people joined together, they can actually improve their conditions.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Ezra Klein

Read More