The site famous for handmade goods is going after Gen Z.

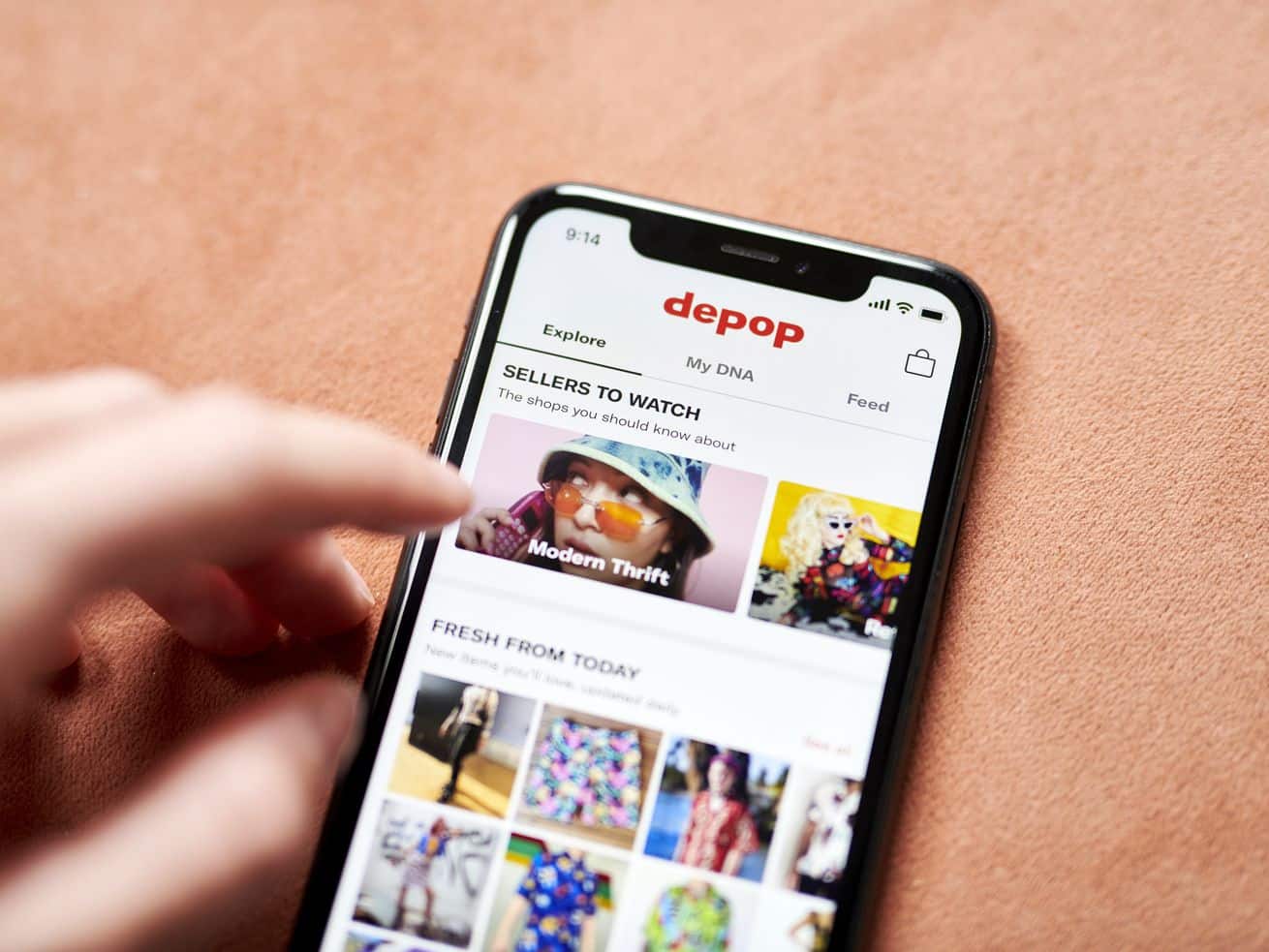

On Wednesday, the shopping site Etsy announced that it was buying Depop for $1.625 billion in a mostly cash deal. Depop, a secondhand shopping platform that’s designed for the age of influencers selling stuff on social media, will continue to operate as its own standalone marketplace. Etsy, meanwhile, says by acquiring the platform it’s adding “the resale home for Gen Z consumers” to its roster.

Perhaps best known for kitschy home decor, vintage clothes, and handmade goods, Etsy is staking its claim on a much younger generation of sellers and shoppers with the Depop purchase, rather than trying to reach those buyers on its own platform. The acquisition makes some business sense, too, as these two companies have a similar model: connecting independent sellers of goods to buyers. Still, Etsy is better known for homemade goods and crafts, while Depop is most famous for selling clothes.

But these two platforms have also cultivated buyers and sellers with profoundly different approaches to social media and online shopping, so merging their styles could be a struggle. The Depop deal comes as Etsy says it wants to become the home of multiple e-commerce brands that cater to new audiences (Etsy bought Reverb, a marketplace for used musical instruments and equipment, back in 2019). At the same time, the company might have a lot to gain from Depop’s influencer-based approach to selling clothing online.

Founded in 2011, Depop has become the secondhand marketplace built for a new generation of social media users. Some 90 percent of Depop users are younger than 26, and the platform is supposed to be the 10th most visited shopping site among Gen Z-ers in the country. Like Poshmark or Mercari, Depop includes a social component to the buying and selling experience. Sellers manage their own profiles and accounts, and many model their own clothes. Some sellers also repurpose vintage clothing, adding a handmade component to certain products. On Depop, for instance, a buyer might find a pair of deconstructed sneakers repurposed as a top or purses made of woven-together candy wrappers. This sort of thing could line up with the crafting tradition at Etsy.

But part of what makes Depop distinct — and valuable to Etsy — is that it encourages a very specific strategy for sellers, encouraging an extremely online, highly social, and younger aesthetic. The fact that Depop looks more like a social network than Etsy matters for this approach. Depop sellers are encouraged to promote their own shop profiles, especially on Instagram, which Depop says is “one of the best ways to build your brand and your customer base.” Sellers and buyers will often turn to other platforms, like TikTok and YouTube, where there’s a broader community of teens and 20-somethings focused on secondhand fashion.

Depop says its mission is building a “community-powered fashion ecosystem that’s kinder on the planet and kinder to people.” The platform has prioritized the sale of used clothing, which can curtail the environmental harms of fast fashion. And Depop has also benefited not only from the growth of social media communities interested in secondhand fashion but also those centered on climate change. The approach seems to work: In 2020, Depop made $70 million in revenue, and the company had 4 million active buyers and 2 million active sellers.

The divide between the Depop and Etsy brands, however, highlights the differences in the types of buyers and sellers the two platforms attract and how they spend their time online. On TikTok, Etsy has about 16,000 followers, while Depop has more than 140,000 followers. (Snapchat, meanwhile, has boasted about its work with Depop as an advertising success story.) Compare those metrics to social media platforms whose users skew a bit older: Etsy has 2 million followers on Twitter and more than 4 million “Likes” on Facebook, while Depop has just over 150,000 followers on Twitter and just under 70,000 “Likes” on Facebook.

Etsy, which was founded in 2005, has had growing pains in recent years. While it’s focused on a homey arts-and-craft aesthetic, the company has struggled to merge its do-gooder mission with corporate realities. In 2017, two years after the company went public, 15 percent of Etsy’s workforce was laid off, and a new CEO, Josh Silverman, took over with the aim to raise profits. Silverman is still the CEO and seems to be focused on building a set of e-commerce brands that do similar things but come with their own personalities.

Lately, there’s also growing debate about the consequences of Depop’s growth. The platform has contributed to a phenomenon of sellers scouring thrift stores to find items that can be marketed for far more than they were purchased for, and sometimes broadcasting their findings on platforms like YouTube. That’s fueled criticism that Depop, among other sites, has helped established another cycle of waste within reused clothing marketplaces while driving up prices at thrift stores, as Vox’s Terry Nguyen explained earlier this year. The platform has also been criticized for lacking body diversity and contributing to sizeism.

Still, Etsy leadership seems to think the e-commerce platforms will serve as complements.

“Depop is a vibrant, two-sided marketplace with a passionate community, a highly-differentiated offering of unique items, and we believe significant potential to further scale,” Silverman said in announcing the acquisition. “We see significant opportunities for shared expertise and growth synergies across what will now be a tremendous ‘house of brands’ portfolio of individually distinct, and very special, e-commerce brands.”

While buying Depop is an easy way for Etsy to find a new generation of shoppers and buyers and keep Etsy current, it’s not clear how Depop’s community of sellers or shoppers will react to the sale. Still, it’s a reminder that as shoppers continue to sour on fast fashion, there is still money to be made on used clothes.

Author: Rebecca Heilweil

Read More