The death penalty is slowly disappearing in the United States, but its death throes are getting ugly.

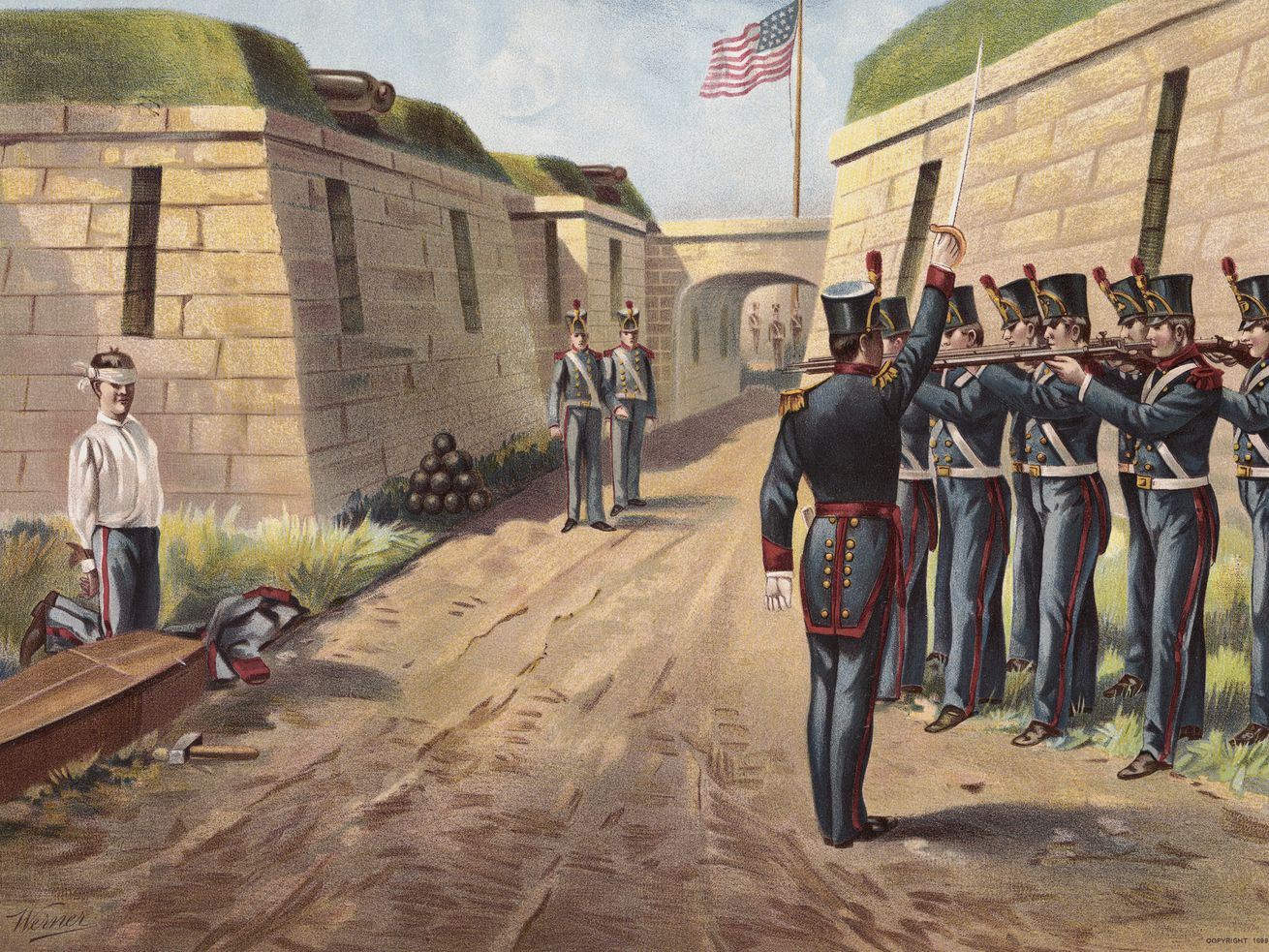

On Monday, the Associated Press ran a headline that reads like something from the end of the 19th century: “New law makes inmates choose electric chair or firing squad.”

The law referenced in the headline is a bill signed by South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster (R) on Monday, which permits the state to kill death row inmates using a firing squad. South Carolina is now one of four states, along with Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Utah, where the practice is lawful.

Previously, South Carolina law provided that all death row inmates would be executed by lethal injection unless they chose to be killed by an electric chair instead. The new law makes electrocution the default punishment, while allowing inmates to choose to be killed by lethal injection or a firing squad — although they can only choose lethal injection “if it is available at the time of election.”

It’s a brutal solution to a problem that’s faced the minority of states that still execute people for about the past decade: the increasing unavailability of the drugs used to do so.

Though execution protocols can vary from state to state, lethal injections are typically performed using a three-drug combination — an anesthetic to knock out the person and dull their pain, a paralytic, and then a toxic drug that stops their heart. But many pharmaceutical companies that make anesthetic drugs refuse to sell their products for use in executions. Others are located in Europe and subject to a European Union export ban targeting a drug that was commonly used in executions.

The result is that death penalty states have struggled to obtain reliable execution drugs. Some states used unsuitable or poor-quality drugs, leading to high-profile cases including one in which a man died in a prolonged state of visible agony. A few prominent judges have argued that firing squads are preferable to lethal injection in part because people who are executed by firing squads are less likely to suffer before dying.

Other states largely suspended executions while they try to track down new drugs — South Carolina last killed an inmate in 2011.

The state’s new law is an attempt to break this impasse and allow people to be killed by the state, even if South Carolina is unable to obtain new lethal injection drugs.

For now, South Carolina’s solution to the drug shortage appears to be fairly novel. Though three other states permit firing squads, only Utah has executed anyone using this method in recent decades. And the firing squad hasn’t been used to execute anyone since 2010.

Nevertheless, the shortage of execution drugs appears to be a persistent problem. So other death penalty states could easily follow South Carolina’s lead, especially if the state’s new law is upheld by the courts.

And proponents of the death penalty have good reason to be optimistic that South Carolina’s law will be upheld. While the new law is already being challenged in court, the Supreme Court has largely paved the way for states to experiment with unusual and potentially cruel methods of execution.

South Carolina is swimming against a broader anti-death penalty tide

The Supreme Court briefly abolished the death penalty in 1972. Four years later, in Gregg v. Georgia (1976), the Court allowed death sentences to resume, but only if states had very specific procedural safeguards to help ensure that only people whom the justice system considered the worst criminals were executed. (Though, in practice, courts applying Gregg’s framework are still much more likely to sentence Black defendants and people who cannot afford good legal counsel to die.)

Gregg upheld a Georgia statute allowing prosecutors to argue that a death sentence was warranted because “aggravating circumstances” were present, such as if the offender had a history of serious violent crime. Meanwhile, defense attorneys could argue that “mitigating circumstances” justify a lesser penalty, such as if the defendant was abused as a child or had a mental illness. Defendants could only be sentenced to die if a jury determined that the aggravating factors outweighed the mitigating factors.

Nevertheless, this weighing test is now a keystone of capital trials in the United States, and scholars and advocates who study the death penalty often refer to 1976 as the beginning of the modern legal regime governing death sentences.

Shortly after Gregg, the number of death sentences handed down every year by courts in the United States rose to between 250 and 300, and it hovered in that range for most of the 1980s and 1990s. Then, starting around the year 2000, the number of new death sentences handed down every year began a sharp downward trend, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22180571/SentenceTrends2020.png) Death Penalty Information Center

Death Penalty Information CenterThe number of executions in the United States has similarly collapsed. Only 17 people were executed in 2020, and that number would have been much lower if the Trump administration hadn’t resumed federal executions for the first time in nearly two decades (though, admittedly, it might have also been higher if the pandemic hadn’t discouraged prisons from gathering prison officials and witnesses for an execution). Only five states — Texas, Alabama, Georgia, Missouri, and Tennessee — performed an execution in 2020. And only one state, Texas, killed more than one death row inmate in 2020.

There are several possible explanations for this collapse in death sentences and executions. The number of homicide crimes fell sharply between 1991 and 2010 — although not far enough to account for the entirety of the drop in death sentences. Also, while the death penalty still enjoys majority support in the United States, public support for it is now at its lowest point since the early 1970s.

More than half of all states either ban the death penalty or have a moratorium in place suspending executions. Earlier this year, Virginia became the first Southern state to ban the death penalty — a significant landmark because Virginia used to execute more people than any state other than Texas.

Meanwhile, many death penalty states enacted laws providing more resources to capital defense lawyers in the last four decades, and several nonprofits formed to help ensure that capital defendants receive an adequate defense. As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said in 2001, “People who are well represented at trial do not get the death penalty.”

So states like South Carolina, which are so eager to perform executions that they are willing to use antiquated practices like the electric chair or a firing squad, are bucking a much broader national trend. That said, it remains to be seen whether this trend will continue, due to a Supreme Court that is more supportive of the death penalty than any Court in the modern age.

The current Supreme Court is hyperprotective of the death penalty

There was a time when capital defense lawyers might have been able to argue that unusually barbaric execution practices violate the Constitution. But that time has likely passed, at least with respect to methods like electrocution or a firing squad. The Supreme Court has spent the past six years shoring up the death penalty against claims that particularly cruel modern forms of execution are unconstitutional.

Until the mid-2010s, it even seemed possible that the death penalty itself would be declared unconstitutional. The Eighth Amendment forbids “cruel and unusual punishments,” and, at least until very recently, the Supreme Court believed that this amendment “must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.”

Thus, as a punishment grew more and more “unusual,” it became more constitutionally suspect. As the death penalty faded away in most of the country, there was a very strong legal argument that all death sentences were unconstitutional.

Meanwhile, while states were struggling to find execution drugs in the early 2010s, capital defense lawyers launched what seemed, at the time, like a promising legal attack on lethal injections.

By the mid-2010s, there was a fair amount of evidence that at least some of the three-drug combinations used in executions did not actually prevent people from experiencing excruciating pain while they were dying — especially in states that were resorting to unreliable anesthetics because the companies that made reliable painkillers refused to sell their drugs to executioners. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in 2015, lethal injection using unreliable drugs “may well be the chemical equivalent of being burned at the stake.”

But Sotomayor wrote these words in a dissenting opinion. The question of whether at least some lethal injection protocols are an unconstitutional cruel and unusual punishment reached the Supreme Court in Glossip v. Gross (2015), and Justice Samuel Alito’s majority opinion in Glossip rescued lethal injections largely by assuming the opinion’s own conclusion.

“Our decisions in this area have been animated in part by the recognition that because it is settled that capital punishment is constitutional, it necessarily follows that there must be a [constitutional] means of carrying it out,” Alito wrote. If you begin with the assumption that there must be a death penalty, then an attack on the primary method states use to kill people becomes suspect.

At oral argument, Alito laid the blame for tortured inmates at the feet of pharmaceutical companies that refused to be complicit in executions. “Executions could be carried out painlessly,” he claimed. The reason inmates were suffering was because of what Alito described as a “guerrilla war against the death penalty which consists of efforts to make it impossible for the States to obtain drugs that could be used to carry out capital punishment with little, if any, pain.”

The effective holding of Glossip, in other words, was that if death penalty opponents made it too difficult to execute people without causing them great pain, then states were free to torture people to death.

Then the Court went even further in Bucklew v. Precythe in 2019.

Though Bucklew does not explicitly overrule the long line of cases holding that courts should look to “evolving standards of decency” when interpreting the Eighth Amendment, Justice Neil Gorsuch’s majority opinion ignores that framework and substitutes a different, much narrower approach to the Eighth Amendment.

Gorsuch’s opinion in Bucklew does list some methods of execution that are not allowed — “dragging the prisoner to the place of execution, disemboweling, quartering, public dissection, and burning alive” — but he wrote that these forms of execution violate the Eighth Amendment because “by the time of the founding, these methods had long fallen out of use and so had become ‘unusual.’”

Thus, while pre-Bucklew decisions asked if a particular punishment was unusual today, Gorsuch asked whether it was unusual “by the time of the founding.” That suggests that a wide array of relatively modern punishments, including lethal injection, electrocution, and firing squads, are now immune from constitutional challenge.

States like South Carolina, in other words, can be fairly confident that the Supreme Court will bless their decision to revive methods of execution that have largely fallen out of favor with modern society.

Firing squads might actually be less cruel than lethal injection

In 2017, a death row inmate named Thomas Arthur brought a very unusual claim to the Supreme Court. Arthur was scheduled to be executed by the state of Alabama, and Alabama planned to kill him using a three-drug protocol that included a notoriously unreliable anesthetic. He asked the Court to allow him to be killed by firing squad instead because he thought such a death would be less painful than the fate Alabama intended for him.

Though the Court rejected this request in Arthur v. Dunn (2017), Sotomayor once again dissented. Citing evidence suggesting “that a competently performed shooting may cause nearly instant death.” Sotomayor wrote that “condemned prisoners, like Arthur, might find more dignity in an instantaneous death rather than prolonged torture on a medical gurney.”

Just as significantly, Sotomayor indicted the entire process of using toxic drugs to kill people, because it sanitized the process of executions without rendering them any less cruel. “States have designed lethal-injection protocols with a view toward protecting their own dignity,” she wrote, “but they should not be permitted to shield the true horror of executions from official and public view.”

A lethal injection can appear like a sterile medical procedure, where the person being executed seems to slip into a peaceful sleep. But there’s no denying what the state is doing when it orders a line of shooters to simultaneously fire bullets into a person’s heart.

So, if we accept Alito’s view that there must be a death penalty in this country — and it appears likely that a 6-3 Republican Supreme Court will accept this viewpoint for the foreseeable future — there are plausible reasons to prefer South Carolina’s new firing squads to lethal injections. Inmates executed by firing squad appear to be less likely to experience the prolonged agony faced by many people who are executed by lethal drugs.

And if South Carolina insists on killing people, it will be harder to ignore the enormity of what the state is doing.

Author: Ian Millhiser

Read More