Racist lawmakers built Georgia’s election system — and it could affect the balance of the Senate.

America might not know which party will control the next US Senate until January — all due to Georgia’s peculiar election system rooted in the Jim Crow era.

To back up: In Georgia, no candidate can advance through a primary or a general election system without first earning more than 50 percent of the votes. If no one does, the top two vote getters advance to a runoff election, ensuring that one will earn the majority of votes cast.

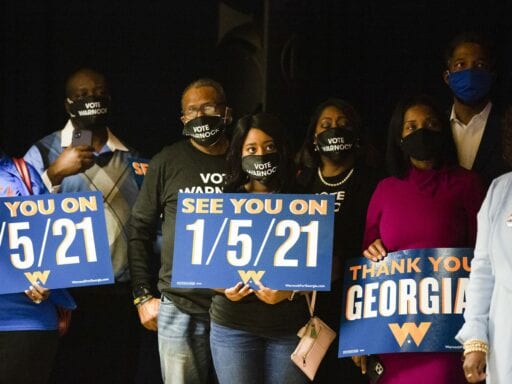

This year, the state’s two Senate races — one regular, the other a special election to fill the remainder of a retired senator’s seat — have gone to a runoff. The first will be between Sen. David Perdue and Democrat Jon Ossoff; the latter will be between Republican Sen. Kelly Loeffler and Democratic Rev. Raphael Warnock.

At first glance, requiring majorities for an outright victory seems inoffensive — the person who wins has to be chosen by most of the people who cast their votes. In theory, this would force candidates to appeal to more voters instead of winning with a large plurality of votes while holding views anathema to the majority of the electorate.

But Georgia’s runoff system has a darker origin: Many historians say it was designed to make it harder for the preferred candidates of Black voters to win, and to suppress Black political power.

The history of Georgia’s runoff system

The origin of Georgia’s runoff system is a little complicated.

It effectively starts in 1962, when the Supreme Court struck down Georgia’s old electoral system. That older system, called a “county-unit system,” was created 45 years prior to amplify rural voters’ power while disadvantaging Black voters’, and was “kind of a poor man’s Electoral College,” University of Georgia political science professor Charles Bullock told Vox.

Forced to come up with a new system, Georgia created one intended to continue undermining Black voters’ influence. That was the runoff system, whose origins were detailed in a 2007 Interior Department report:

In 1963, state representative Denmark Groover from Macon introduced a proposal to apply majority-vote, runoff election rules to all local, state, and federal offices. A staunch segregationist, Groover’s hostility to black voting was reinforced by personal experience. Having served as a state representative in the early 1950s, Groover was defeated for election to the House in 1958. The Macon politico blamed his loss on “Negro bloc voting.” He carried the white vote, but his opponent triumphed by garnering black ballots by a five-to-one margin.

Groover soon devised a way to challenge growing black political strength. Elected to the House again in 1962, he led the fight to enact a majority vote, runoff rule for all county and state contests in both primary and general elections. Until 1963, plurality voting was widely used in Georgia county elections…

Essentially, Groover wanted to stop Black Georgians from voting as a “bloc” — that is, overwhelmingly for one candidate or party — while white Georgians split their votes among many candidates. In a plurality system, if Black voters were able to keep a coalition behind one candidate, they wouldn’t need the support of many white voters for their preferred candidate to win elections.

The method was popular across the former Confederacy: Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Texas all have general election runoffs. As the Washington Post reported, just two non-Southern states have runoff rules, and those “almost never matter”:

In South Dakota, candidates for U.S. Senate, U.S. representative and governor must compete in a runoff if no one reaches 35 percent of the vote. In Vermont, a runoff is ordered if two candidates finish with the same number of votes.

There are some, like Bullock, who don’t believe this was designed to be a racially discriminatory institution, pointing out that the use of runoffs began at a time when Black voters had already been largely eliminated from the voter rolls. Others have said there were good governance reasons for implementing the runoff system.

However, Cal Jillson, a professor at Southern Methodist University, told the Washington Post that most of the states that adopted runoff systems did it to “ … maintain white Democratic domination of local politics. Letters and speeches that survive from the period show race was very much on the minds of those Democrats who advocated the primary-runoff process. ‘People had no misgivings about stating their real intentions and stating them in racial terms,’” Jillson told the paper.

Moreover, arguments about good governance and race neutrality are hard to square with Groover’s blatant racism as well as the context in which these decisions were being made — a time when Georgia and other Southern states were fighting to maintain white supremacy in voting institutions.

As if to simplify the historical record, decades after Groover fought to institute run-off elections, he admitted: “I was a segregationist. I was a county unit man. But if you want to establish if I was racially prejudiced. I was. If you want to establish that some of my political activity was racially motivated, it was.”

Groover also confirmed that he “used the phrase ‘bloc voting’ as a racist euphemism for Negro voting.” A DeKalb County representative who supported Groover “remembered Groover saying on the House floor: ‘[W]e have got to go the majority vote because all we have to have is a plurality and the Negroes and the pressure groups and special interests are going to manipulate this State and take charge if we don’t go for the majority vote.”

So that all seems pretty clear.

The potential effect overturning Georgia’s runoff system could have on Black political power

But did these efforts actually work as intended?

The 1990 Justice Department seemed to think so. That year, the DOJ sued to overturn the runoff system. Assistant Attorney General For Civil Rights John R. Dunne told the Los Angeles Times at the time that the runoff system has had “a demonstrably chilling effect on the ability of blacks to become candidates for public office,” and called the requirement “an electoral steroid for white candidates.”

The Justice Department cited elections in more than 20 Georgia counties “where at least 35 black candidates won the most votes in their initial primaries, but then lost in runoffs as voters coalesced around a white opponent.” The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights praised the suit contemporaneously, favorably comparing the George H.W. Bush DOJ with the Reagan administration. The American Civil Liberties Union, which had also unsuccessfully filed suit to discard the majority-vote requirement, applauded the lawsuit.

But there was real dissent around what eliminating this system would have done.

Thirty years ago, University of Virginia political scientist Larry Sabato told the Los Angeles Times that “the Republican Justice Department in the name of minority rights is pursuing policies that will help Republicans.”

The logic here is that if the runoff system is eliminated, Black candidates in Democratic primaries are more likely to make it to the general election. Some observers believed that white Democrats were harder to defeat than Black Democrats. Therefore, the argument goes that while eliminating the runoff system could help Black candidates advance to the general election more often, Republicans would have an easier time beating them when they got there than their white counterparts.

The DOJ’s lawsuit was eventually consolidated with Brooks v. Miller, where 27 Black voters unsuccessfully challenged the majority-vote requirement. In 1998, the 11th Circuit Court found that the plaintiffs were unable to prove that changing the runoff system would increase the number of Black elected officials. They also found that “discrimination was not a substantial or motivating factor behind enactment of the majority-vote provision.”

The court agreed that “the virus of race-consciousness was in the air” when majority voting was instituted but that “the plaintiffs failed to prove that the majority-vote requirement was ‘infected thusly.”

The only large data set presented in the case came from the state of Georgia’s expert witness. He looked at Georgia’s primary elections from 1970 to 1995 and found that there were 278 runoffs involving a Black candidate running against a white candidate. In 85 of these cases, the candidate who won the plurality of votes in the initial primary lost in the runoff. 65 percent of those cases featured a Black candidate losing in the runoff after their initial victory. However, the defendants convinced the court that “the disparity of outcomes … was attributable to the relative strength of individual candidates,” not due to the unfairness of the runoff system.

At the end of the day, we don’t know a lot. It’s obvious that a lot of racist people wanted to dilute Black voting power in 1960s Georgia. Many of these people were in favor of eliminating the plurality system and instituting runoffs.

However, it’s difficult to know how this rule has affected Black representation and political potency in the state, since it’s impossible to determine the counterfactuals. For instance, in a counterfactual world without a looming runoff system, Republican Rep. Doug Collins or Loeffler might have withdrawn from the “jungle primary” to ensure Warnock couldn’t win in a plurality election. Who knows?

The fact of the matter is, all things equal, without Georgia’s runoff system, Raphael Warnock would have been elected outright to the US Senate.

But so would David Perdue.

Author: Jerusalem Demsas

Read More