Streaming services’ playlists make it easier for listeners to find music worth playing. But experts say they’re also breaking fans’ relationships with artists.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21899595/VOX_The_Highlight_Box_Logo_Horizontal.png)

In 2018, Trevor Daniel released the song “Falling” to little fanfare. Its tame take on emo-rap couldn’t hold a candle to the darker more confessional acts like Lil Uzi Vert and Juice WRLD, who pioneered the sound.

But two years later, “Falling” blew up, thanks to the internet. First, it was picked up by influencers on Instagram, then it became a TikTok meme featured in more than 3 million videos. The social media hype led to traditional media success: The song spent 38 weeks on Billboard’s Hot 100, peaking at 17. It was streamed more than a billion times on Spotify, where it’s featured on prominent playlists like “Chill Hits,” “Beast Mode,” and “Top Gaming Hits.”

Then Daniel attempted a star-studded follow-up, ”Past Life,” featuring Selena Gomez and produced by Finneas. The song peaked at No. 77 on Billboard, left the charts in 5 weeks and had just 10 percent of the streams that “Falling” achieved on Spotify. Daniels has yet to come close to replicating the accomplishment of “Falling.”

Success in the music industry used to rely on radio plays and premium retail “endcap” placements (where stores like Best Buy gave album releases prime real estate). It’s no secret that streaming has changed everything, providing unfettered access to the largest catalog of music in human history.

It also presents a paradox of choice: What should you listen to when you can hear nearly any song that’s ever been recorded? With more and more songs released by more and more musicians on more and more platforms — and less emphasis on traditional media to tell listeners what to like — the sprawl of streaming has upended what it means to be a pop star. For an artist like Daniels, streaming both gave him the opportunity to break out from obscurity and made it exponentially more difficult to have a follow-up hit. That’s because like so many other viral hits, the song, not the artist, became the asset.

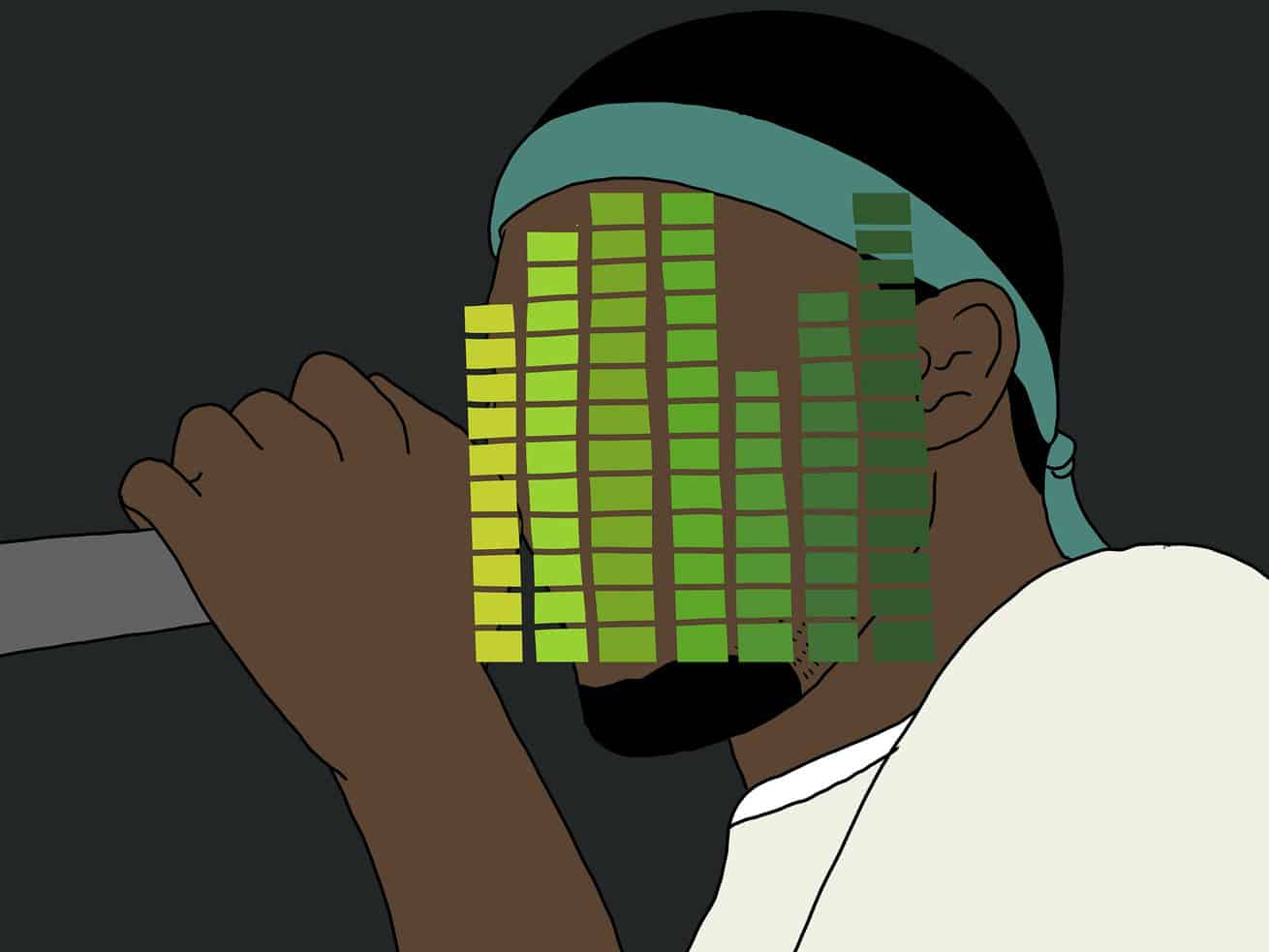

“Streaming is a great way to make an artist faceless,” says Lucas Keller, the CEO of the entertainment management company Milk & Honey, which manages some of the biggest producers and songwriters working today. His roster has written for artists including BTS, Ariana Grande, and Gwen Stefani — at one point in 2019, 10 of the songs on top 40 were written or produced by Milk & Honey talent.

“The song,” Keller says, “becomes bigger than the artist.”

He cites James Arthur, whose song “Say You Won’t Let Go” reached No. 11 on Billboard’s Hot 100 in 2017. It’s a mid-tempo acoustic ballad with a gentle hip-hop groove that fits equally well on pop radio as it does in alternative and adult contemporary formats. And though appearances on Spotify playlists like Mood Booster, Happy This!, Warm Fuzzy Feeling, Chill Hits, and Alone Again helped generate billions of streams for the song and a number of follow-up singles, Arthur has yet to land another Top 40 hit.

There’s more competition on the charts than ever. In 2020, there were more songs on Billboard’s Hot 100 than any year since the 1960s, the last decade when singles, and not albums, drove the recording industry. In 2019, 40,000 songs were uploaded daily to Spotify, according to Music Business Worldwide; in 2021, that number has grown to 60,000. For artists, as the volume of new music releases increases, it’s becoming more difficult to be heard.

Keller puts this volume in perspective: “If you took all of the premium music released on a digital storefront right now, and tried to jam it into a record store, it’d need to be a Home Depot.”

To help listeners find their way in the endless aisles of digital music, streaming providers created playlists — but this new way of listening has created unintended consequences for artists and songwriters. Today, three services make up two-thirds of the streaming economy: Spotify, which has an estimated 32 percent of the market, Apple Music (18 percent), and Amazon Music (14 percent). But Spotify dominates the conversation both because of its market power and its immensely popular playlists. In 2017, 68 percent of all listening on Spotify was from a company or user playlist, according to the company’s 2018 Securities and Exchange Commission filing. Its platform has more than 4 billion playlists, 3,000 of which are owned by Spotify, curated by a mix of algorithms and editors.

Its most prominent playlists have serious cultural power. RapCaviar shapes the sound of hip-hop, and can turn indie rappers into household names. The genre-agnostic, slightly quirky playlist Lorem curates the vibe for Spotify’s Gen Z listeners. In 2020, listeners ages 16 to 40 used playlists as their primary source for discovering new music on the platform, according to the company. So today, a placement atop one of its playlists can make or break a song.

Spotify isn’t shy about the marketing power of its playlists. In its SEC filing, the company wrote as much, crediting Lorde’s breakout global success to her placement on a single playlist: Sean Parker’s Hipster International. But her example may be an outlier. The challenge for most artists is that playlist listeners frequently don’t know who they’re listening to. A song with high completion rates on a playlist might end up on more playlists, accumulating millions of streams for an artist who remains effectively nameless. In the best-case scenario, these streams, which pay very low royalties compared to radio, could help land the song a coveted advertisement, or better yet, pique the attention of Top 40 radio programmers.

But pop stardom has always relied on a blend of catchy songs and compelling personas. “The music video era gave you a big dose of their personality whenever you discovered new songs. And the same thing with an album,” says music producer Jesse Cannon.

An MTV study on fandom showed that fans expect to have direct interaction with artists. But in a music economy built on playlists, the listener is much less likely to be aware of who they’re listening to. Playlists are a “lean back” experience. You choose the mood you’re in, and the music just flows. Cannon believes that playlisting is breaking the fan-artist connection: “When we’re making playlists, there’s no depth whatsoever to the relationship.”

Even if playlists work against persona-based star power, artists are still desperate to appear on them to create buzz for their music. “The buzz-making, hit-making economy has gone from top down, to bottom up,” says Slate’s chart expert Chris Molanphy. “It used to be that you pushed things at radio, and that made people buy the single, buy the album.”

Now songs develop on social media platforms, and grow on playlists, before making it to radio. Music marketers have repositioned themselves to build influence over TikTok feeds. PR firms market their ability to get their clients on playlists, though Spotify maintains a stance of editorial independence.

Even success on a small playlist helps boost an artist’s chances of getting noticed by an algorithm or editor and being placed on a larger playlist. (While researching this article, I received an email from an independent artist asking for placement on my playlist with 199 followers: “I just came across your playlist, ‘Silk Sonic’s Retro Soul,’” they wrote. “I have a song … that I think would be perfect for the playlist.” A link to the song was attached.)

This is one way would-be pop stars suffer in the new music economy: Playlists have become such an essential part of a song’s success that an underworld of playlist promoters have emerged to exploit this musical ponzi scheme. Independent artists often pay hundreds of dollars to them hoping for exclusive placements on popular playlists. The labels are in on it, too. Spotify provides an egalitarian service where everyone, whether distributed by an indie or major label, submits songs for playlisting. But according to Cannon, labels have direct access to the company through reps, and regularly wine-and-dine key decision makers at the company.

Spotify’s guidelines do not allow for paid playlist promotion. Still, thousands of pay-to-play lists exist on the platform. And Spotify has its own program to boost the likelihood of landing on a playlist if artists and songwriters are willing to accept a lower royalty rate on promoted songs. Called “Discovery Mode,” it’s currently being probed by Congress for the practice of forcing lower royalties; representatives from the House Judiciary Committee want to find out if Spotify is limiting choice and hurting artist revenues. Spotify has argued that this program is an essential way for artists to highlight which songs they want to prioritize to be heard, even if they’re not seen.

For upstart musicians, the bottom-up model is the only choice. Without the old gatekeepers, in rare cases, indie artists can break outside of the major-label ecosystem. Cannon cites Penelope Scott as a prototypical example. She makes obscure baroque punk, but her music has expanded beyond her niche. Her song “Rät” has “lyrics that are so extremely online” that they’ve inspired thousands of TikTok videos, and that led to Spotify playlists and even a place on Billboard’s Hot Rock & Alternative charts. “That is what gets around the gatekeeper,” says Cannon. “This girl reached 3 million monthly listeners without any coverage.”

But overnight viral stars are rare, and building a lasting audience is harder than ever as social media platforms are flooded by celebrities and established acts. Many artists who break out on TikTok become one-hit wonders. Their songs eclipse their short-lived public identities as audiences move onto the next meme. And those who do break out still need to work their way up the ladder from social media to streaming, and finally, to radio to reap financial rewards.

Performers aren’t the only ones affected by streaming. Though streaming has been a financial boon for labels, songwriters still depend on radio play for the bulk of their income — radio pays much higher royalties to songwriters compared to streaming. Emily Warren, who has written hits for Dua Lipa and the Chainsmokers among many others, told me that she knows songwriters with hundreds of millions of streams and Grammy nominations who still drive Uber for a living. But she says that a songwriter with just two big radio hits is set up to retire.

These distorted economics change the kind of songs that are written. “[Songwriters] are just chasing radio. The only way a writer can make any money is if they have a radio single,” Warren says. Even though it’s been widely reported that streaming has changed the sound of pop music, artists still fight for radio listeners, who skew older and more conservative in their tastes.

There may be some truth to the age-old criticism of all pop music sounding the same. Before iTunes started selling songs as singles, songwriters could make money off of deep album cuts: “There used to be so much money and value in any kind of song, and anywhere on the album. You could have track eight on an album that had a big single and you would make so much money off of it,” Warren says. She believes that album sales allowed songwriters to take more risks and find new sounds. By comparison, the Top 40 radio format of old-school anthemic choruses is creatively restraining. Warren says that these financial incentives are holding popular music back: “If songwriters start being compensated, there will be a musical renaissance.”

As artist and songwriter Julia Michaels puts it, “With streaming, songwriters are lucky if they make anything. If you don’t have the single, you’re basically fucked.” And in the bottom-up method of hit-making, promoting a single across every platform is exhausting.

Michaels believes that the creative laborers in popular music are feeling pressure to compete with every online influencer: “It is definitely a scary time for songwriters. And it’s kind of a scary time to be an artist, too. There’s a lot of expectations. You have to be a TikTok star. You have to be on social media all the time. You have to be a model.”

Today’s streaming economy looks a lot like the larger economy. Michaels explains that now, “if you’re not in the top 1 percent, it is not lucrative at all.” In fact, the pool that makes a decent paycheck is much smaller than the 1 percent — only 13,400 artists earned more than $50,000 on Spotify in 2020. Just 870 made it rich, bringing in more than $1 million.

As for Trevor Daniel? Chart whisperer Molanphy says that he’s in the “middle of the pack — neither a nobody, nor a chart-topper — who now has to find his way in this weird new economy of hit-making.” With so much financial uncertainty in music, it’s not surprising that so many artists are selling their catalogs and speculating with cryptocurrencies and NFTs.

The age-old business of writing and releasing songs has been upended. Now every song has to find a life on a half-dozen different formats to be a hit. What was never easy is only getting harder. While we’re daydreaming to our “Chill Vibes” playlist, artists and songwriters are flailing to get our attention.

Charlie Harding is a songwriter and executive producer and co-host of Vox Media’s Switched on Pop podcast, which looks at phenomena in pop music.

Author: Charlie Harding

Read More