Millennials and Gen Z are revisiting indie pop, grunge fashion, and the early 2010s Tumblr aesthetic. Wouldn’t it be nice if life still looked like that?

POV: It’s 2013. You’re listening to a Purity Ring song on your iPhone 4S, wearing an American Apparel tennis skirt while reblogging a Tumblr post shipping Santana and Brittany from Glee. Bing! Your friend just texted you a hilarious Harlem Shake Vine. You text back “lmao DEAD.”

This is, statistically, probably not what you were doing in 2013. But wouldn’t it be fun to pretend it was?

Reliving a very specific subculture from the period that roughly spans from 2009 to 2014 — the era of indie pop, ironically oversize eyeglasses, and late-wave finger mustaches — is what countless millennials and Gen Z kids are doing right now, online and in their bedrooms. “Bop or flop?” posits a TikTok trend asking users to rate “coming-of-age indie pop bangers” from those years. Girls are recreating outfits inspired by hyper-stylized image macros of flower crowns and band T-shirts they loved in middle school. Others are digging back into their angst-ridden social media posts from their adolescent and teen years. “If you were on Tumblr in 2013-2014 you should qualify for a senior discount,” reads one self-deprecating video from the genre, as though the era were several generations ago and not less than a decade.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19948062/Screen_Shot_2020_05_05_at_10.56.03_AM.png) Tumblr

Tumblr“We’re seeing posts literally float to the surface from 10 years ago,” says Cortney Kerans, the head of communications at Tumblr. She noticed something strange was going on when Megamind, an animated movie from 2010, was the most popular film on the platform the week of March 16. “It made no sense,” she says. “There was no news about it, no piece of art that was going viral.” When Kerans took a deep dive into what else was trending, she noticed a pattern: Everyone who remembers the internet in the early 2010s was rediscovering their fantasy favorites, like Twilight and Divergent.

Like junk food, video games, and at-home hair dye, nostalgia is a popular pastime even in normal circumstances, but particularly so in an era where the present feels inescapable. In 2017, millennials flocked to emo-themed concerts to relive the melancholy soundtracks of their youth. In 2018, teens made memes about being nostalgic for 2015, in part because anything before President Trump felt like some long-forgotten past. Now, when a pandemic orders us to stand still at the exact same time, the only way through is back.

For Krystine Batcho, a professor of psychology who studies nostalgia at Le Moyne College, none of this is a surprise. Major life changes, even positive ones — career switch-ups, marriage, moving — always coincide with feelings of wistfulness, a return to a time when things felt simpler and less scary. So does loneliness. “Life as we knew it a month ago might never return in the same form,” she says. “We really do yearn to, if nothing else, be able to visit that past.”

Young people in their late teens and early 20s are already the age group most predisposed to feelings of nostalgia, Batcho explains, because it’s the time in our lives when the trappings of childhood are being left behind for good. (The second most nostalgic demographic is the elderly, but it’s less likely that the years between 2009 and 2014 are “the good old days” they’re thinking of.)

As one might assume, when we’re nostalgic for the past, it isn’t really our old Tumblrs or the movie Megamind that we’re really longing for, but the feelings associated with them. “What people are craving is the period when they had fewer worries, more innocent fun, and greater emotional support during difficult times,” Batcho says. “It was simpler. Now there are all these choices. [Social media] got so complicated that it ruins some of the fun.”

POV: It’s 2020, and you’re in your childhood bedroom as an adult. Not by choice, but because your university closed down the dorms. Your whole life is online now — classes, grocery shopping, friend dates, actual dates. It reminds you of another time in your life when online was the only place that really mattered.

For 18-year-old student Anna Tulenko, that time was 2013. Back then, her all-girls Catholic school had 15 people in each grade, so her real social life was on Tumblr and Instagram, in the fandom communities for alt-pop artists like Troye Sivan, Marina and the Diamonds, and Lana Del Rey.

“The ideal was pastel grunge, the 1975, Arctic Monkeys, American Apparel, black-and-white stripes, and jelly shoes, like you were living in an episode of Skins,” she jokes of the aesthetic she obsessed over at the time. She and a few online friends from the early 2010s made a TikTok video transforming into the Tumblrized version of their younger selves — pigtail buns, chokers, e-girl hearts, knee socks, and chunky platforms, clutching a copy of Lorde’s Pure Heroine. “POV: It’s 2014,” read the caption.

Since she’s been back at her parents’ house in New Jersey, Tulenko says, “I feel like I’ve gone through every phase that I’d been through in early adolescence.” Of all the times to feel nostalgia for, I mention how weird it is that we long for that particular period, which is often one of the worst in our lives. Nobody I know really liked being in seventh grade, but Anna says that’s part of why she’s revisited it. “I think it’s partially because of the melodrama of it all when you’re that age, especially for young girls,” she says. “You feel pretty bad about yourself.” At 18, she’s able to contextualize some of that tween angst. The music she listened to and the clothes she wore in 2014 are “an escape itself, because now the world just feels like such a harsh place, and this was a time before I realized that.”

People are often nostalgic for things that felt horrible at the time. Batcho says part of it is perspective — we realize how pointless our anxieties about boys or acne or friends actually were; we realize that absolutely everyone is miserable in middle school. The other part, though, is that we like what’s familiar. “Right now, for instance, there is so much unfamiliar,” she says, “that even going back to the difficult times is still somewhat comforting.”

POV: It’s 2012. You’re a terrified college transfer in New York City, lonelier than you’ve been since middle school. You pass the time by stumbling through other people’s identities, trying to find one that fits. In lieu of friendships and frat parties, you listen to the sad bands you read about on that niche blog nobody’s heard of.

I hated being 19, but there’s never been a time when I listened to better music. This, of course, is not an objective statement. Every age group believes this — the best music was the kind they listened to when they were the saddest; the best SNL cast was the one from the first time they watched.

But there is something distinctive about the music from our millennium’s angsty teenage years, even though there does not seem to be a good name for what it is or if it can even be described as a genre. “Indie pop” is maybe the best we have, a stepdaughter of the “twee as fuck” indie pop of the 2000s, though it comprises dream pop and alt-rock and electronic music and artists with little in common sonically, like Vampire Weekend and Grimes, Frank Ocean and Robyn.

“It was so exciting. It made me feel so cool and edgy,” says Joel Albers, founder of the Lights & Music Collective, a record label that hosts indie-pop dance parties. “When people started to make laptop music, it opened the floodgates. I remember playing Lady Gaga’s ‘Just Dance,’ which at the time was an indie dance hit but then crossed over to pop, and people would look at me in the gym, like, angrily.” Even back then, no one knew what to call this new kind of music, he remembers. “Everyone called it ‘techno.’ They called Miike Snow, Passion Pit, anything with synthesizers ‘techno.’”

Joel’s traveling dance party has featured precisely this type of music since the music was actually new. In 2013, he threw a club night at a small bar in Seattle called Dance Yourself Clean, after the LCD Soundsystem song, devoted to independent pop artists who didn’t fit with the pulsing EDM beats popular in lounges at the time. Over the next few years, it expanded to Los Angeles and New York City, where there are now a handful of other popular indie pop dance parties that offer a similar escape into a time when the word “hipster” could be a meaningful description of a person.

I went in November with a small group of friends to a Dance Yourself Clean party in Brooklyn, where we sang along to our college playlists full of Phantogram, Miike Snow, Arcade Fire, and MGMT (sure, the MGMT song that everybody knows came out in 2005, but it’s about the vibe). Joel says that the party isn’t meant to be a throwback; it’s meant to be a celebration of indie pop as a genre.

We went for the nostalgia, though. We wanted to hear the kind of music that made us, young people in Brooklyn, feel like even younger people in a grungier and more glamorous Brooklyn. I didn’t even listen to LCD Soundsystem in 2013, but it’s the kind of music that makes you feel like you did.

These songs are now some of the most popular on the hottest social app of the moment. On April 4, 24-year-old model and illustrator Thaddeus Coates posted a “Bop or Chop?” TikTok rating the “early 2010s indie pop coming-of-age songs” from his teenagehood that included Matt & Kim’s “Daylight,” Phoenix’s “1901,” and the undisputed apogee of the genre, “Midnight City” by M83. “It’s infectious; it just radiates,” he says of the music from that time. Lately, as he’s been staying at his childhood home during quarantine, he’s been revisiting the songs he listened to in high school and connecting over shared memories with other former Tumblr kids. “We’re using TikTok to find our tribe,” he says.

Music, and the culture industry at large, is indeed different now. The early 2010s was the heyday for music blogs, where artists would pick up steam via a network of niche websites devoted to up-and-coming acts. Now, much of the music we listen to is dominated by what streaming algorithms demand.

Fandoms for movies, TV shows, and celebrities had not yet gone mainstream — they were a hobby you tended to enjoy in enclosed circles, not publicly, and nobody outside of those circles really seemed to care all that much. Fast fashion existed, but it was not nearly as accessible (and, well, fast) as it is now — thanks to social media, beauty, and fashion trends moving at warp speed. The idea of a “meme” amounted to a cartoon with a caption in the Impact font. Behind all of this has been the ambient noise of a new kind of monoculture, dominated by machine learning.

Nostalgia, like everything else, seems to move quicker now, too. In 2017, the writer Brian Raftery argued that though traditional thinking suggests nostalgia arrives in 20-year cycles (Grease in the ’70s, Dazed and Confused in the ’90s), our “art-absorption metabolisms have been sped up by the web, which often feels like a borderless 24-hour culture klatch, full of nonstop pop-convos about The Stuff We Love.” Now, he says, 20 years is far too long to wait to rediscover old favorites, hence, the mid-aughts revivalism he was writing about then.

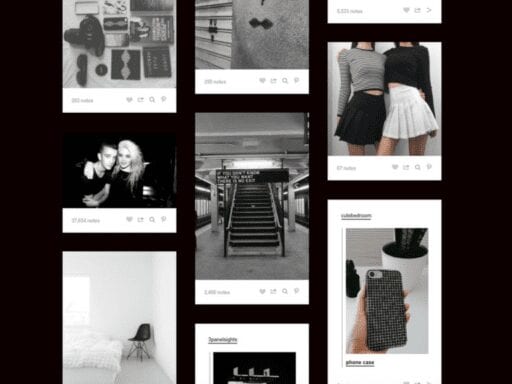

Raftery also predicted that in the future, our cultural nostalgia will be less tied to specific artworks or ideas and more about the technologies on which they spread. Ask anyone who was a very online teenager in the early 2010s and that’s how they’ll describe the thing they’re longing for: the aesthetic of Tumblr, where a high-contrast black-and-white photo of Doc Martens in a puddle overlaid with a quote about being too much or feeling too much passed as profound imagery.

— cam (@camstille) March 30, 2020

Amanda Brennan, the resident “meme librarian” at Tumblr, has seen it all resurface over the past month via users sifting through their old accounts and engaging with posts from a decade ago. “The archive is just such a beautiful view, kind of like this digital diary,” she says.

“People go through hyper-fixations and then jump from one to the other to the other, and Tumblr is kind of like the travel guide through that. It just feels like home.”

I was not a Tumblr teen; I was not listening to Arctic Monkeys or wearing chokers and tennis skirts like a goth Lolita in high school, and odds are neither were you. But this is the beauty of a collective nostalgia for a subculture that existed mostly via shared images and downloaded songs: It’s all still there. You don’t have to have been part of it to understand the longing for what the music and images and styles evoked, or what it felt like to experience them when they were new.

POV: It’s 2020. You are an adult, living a life that is a little more boring than it was a decade ago, stuck at home in the midst of a global pandemic that will probably change the world as we know it. You hear a song that sounds like it could be screamed by a bunch of sad young people at a warehouse party, back when you used to go to warehouse parties, back when people were allowed to have those. How could it have ever been so good?

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Rebecca Jennings

Read More