For as much as I loved season one, UnReal’s scattered, troubled second season killed a lot of that affection. And while I liked the first few episodes of season three, I never found room for the rest of it in my regular viewing rotation. Now, with the addition of an entire other season, it just feels like too much to get caught up on.

But this isn’t really an article about UnReal. It’s an article about second seasons — the most important but most difficult seasons of any TV drama. Nail your second season and you’re almost certainly going to remain on the air for years to come. Flub your second season, like UnReal did, and you’re in trouble. Fall somewhere in the middle and you might get renewed but fail to convince your viewers to emotionally invest at the level a great serialized story requires.

And in the wake of several high-profile second seasons that public consensus has judged on a scale ranging from “mild disappointment” to “outright debacle,” the challenges that arise with season two have become clearer than ever. Just look at The Crown, Stranger Things, This Is Us, The Handmaid’s Tale, and Westworld — the five second-season dramas nominated for the Drama Series Emmy — for some prominent examples.

But here’s the Catch-22 about second seasons: A good way to ensure you have a great second season is to air a somewhat disappointing first season. Yet in the age of Peak TV, airing a disappointing first season is a good way to ensure you don’t get a second season at all.

Exciting first seasons are often easier to pull off with big, high-concept premises — the sorts of premises that often tee up disappointing second seasons

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6441427/americans4.8jennings.0.jpg) FX

FXTraditionally, a TV writing rule of thumb has been that the first few episodes of a show — usually the first six — should basically be remakes of the pilot. The idea is that by simply twisting the dynamics of the pilot in slightly new ways, a show’s early episodes can help viewers catch on to what the premise of the show is and who the characters are. In the pre-DVR era, this made a lot of sense: When most regular viewers of a TV show tended to catch only four to six episodes over the course of its season, it was much more vital to provide them with a firm grounding in what the show was before diverging from it in the slightest.

There were some great shows produced under this model, and it’s probably still the best approach to follow for any series that runs more than 20 episodes per season. But the endless repetition it requires inherently stymies the kind of hardcore serialization that modern television rewards. And back when it was the predominant way of doing things, it left a vague sense in the American TV industry that the first season of a show, at least, should concentrate on underlining the show’s premise, setting up the characters, and making sure viewers are absolutely sure they know what the story is about.

That’s why shows with buzzy first seasons, like Stranger Things and The Handmaid’s Tale, tend to be so premise-heavy. They often have exciting, high-concept premises, or at the very least brand new ways to tell very old stories. They run from peak to peak, exploring new corners of their worlds, often thrillingly.

This is great when you have enough of a story to tell in that first season and can do it in a way that also establishes your characters, your world, and the basic tenets of how your show works. Think of how the first season of Stranger Things told an almost complete story about kids having adventures in the Upside Down, or how the first season of The Handmaid’s Tale mostly faithfully adapted Margaret Atwood’s book.

But you can see the pitfalls of this approach in essentially any show with an exciting first season that later didn’t manage a tremendous second season, which is a pattern that has repeated throughout much of TV history. Think Mr. Robot, or Desperate Housewives, or Heroes, all shows where season two seemingly ran out of story to tell.

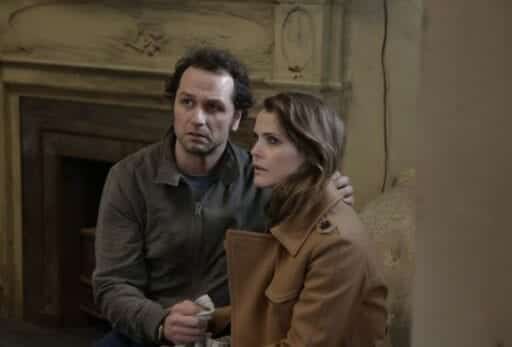

Now let’s compare the “acclaimed first season, disappointing second season” fate to that of one of the other shows nominated for the Best Drama Series Emmy this year: FX’s The Americans. The show’s first season garnered warm notices when it debuted, but some critics, at least, argued that when all was said and done, the first season wasn’t quite everything it could have been, something both FX and the show’s producers seemed to take to heart.

Where season one had overloaded on spy mission of the week stories, as if it wasn’t entirely convinced people would actually want to watch stories about its characters, season two set to work deepening the show’s characters, storytelling, and themes. The Americans ultimately remained on the air for six years, eventually becoming one of the best dramas of the decade and taking a well-deserved victory lap after its roundly praised sixth and final season.

A bunch of other recent-ish shows have followed a similar trajectory. Even if they didn’t run as long or earn the same Emmy recognition as The Americans, shows like HBO’s The Leftovers, AMC’s Halt and Catch Fire, WGN’s Manhattan (which you possibly haven’t even heard of but is now on Hulu), and Sundance’s Rectify (which was critically loved for most of its run but certainly grew in depth and beauty) were all more divisive early on.

The Leftovers spent its first season reiterating the show’s basic premise — 2 percent of the world’s population had disappeared, and people were sad about it — endlessly. Halt and Catch Fire’s first season withheld a key part of its premise (the characters had been lapped in almost every way by their tech industry competitors) until the very end. All these decisions created first seasons that many people found frustrating — but also created the conditions that led to their more creatively successful second seasons.

So what is it about season two that trips up shows with such exciting first seasons, while seeming to boost shows with more disappointing debuts? It’s pretty simple: Season two is when everything deepens, and a TV premise becomes a TV show.

Why so many shows with great first seasons also have disappointing second seasons

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2465088/sopranos.0.jpg) HBO

HBOA hopefully obvious answer to the disappointing second season problem is a basic tenet of human nature: It’s hard to replicate the experience of first watching something and falling in love with it. The sheer thrill that accompanied the slow word-of-mouth excitement that boosted Stranger Things in season one was never going to happen again when the show returned for season two.

But another obvious answer to this problem is that once a first season tells a mostly complete story, it can be incredibly hard to open up that story again to tell more stories. To return to the Stranger Things example, consider how the show opted for a bigger, louder remix of its first season in season two, to the degree that its Big Bad was ultimately just a much larger version of the monsters from season one.

So what’s a TV show to do? Well, let’s take a look at a relatively recent show that managed acclaim in its first and second seasons: Mad Men. Season one was hugely lauded by both critics and Emmy voters, and its second season deftly evaded the sophomore slump label, winning roughly similar levels of praise and awards. The key is that Mad Men spent almost all of its second season deepening the characters who weren’t its protagonist, Don Draper. Something similar happened with Breaking Bad, which didn’t have as acclaimed of a first season as Mad Men but produced a similarly great second season that deepened the ensemble cast in ways season one just couldn’t.

Season two of a great drama usually finds a way to explain why the show isn’t just a story about the protagonist but a story about a whole cast and a whole world. With the premise having been thoroughly explored in season one, the show, by necessity, has to start looking for other ways to tell stories. This usually means turning to the other characters within the ensemble, as we saw with Mad Men and Breaking Bad, but it can sometimes mean pivoting to explore a new corner of the show’s setting (as when The Wire shifted its action to the docks of Baltimore) or diving further into core themes (as when Buffy the Vampire Slayer added a dose of tragic romance to its adolescent angst and found the two tasted great together).

Deepening a show in season two is another a holdover from how TV dramas used to be made. In the days of 22 to 26 episodes per season, the more repetitive first season often felt a little exhausted by its end, while the second season could often feel rejuvenated by new ideas and opportunities as the writers expanded what was possible within the show’s world. It’s no mistake that so many classic broadcast network dramas, from Buffy to The X-Files to Hill Street Blues, either had their best seasons in season two or broke new ground that led to even better seasons later on.

Of course, the disappointing second season isn’t a new invention (plenty of older dramas had big, breakout first seasons followed by bland second seasons), but it has certainly has become more common in the modern, post-DVR era. The struggle comes when a high-concept premise collides with the need to expand a series into something that can repeat itself over and over.

Of this year’s Emmy-nominated second-season dramas, The Crown probably saw the highest level of acclaim for its second season, and that was because it has a rock-solid “royal crisis of the week” format. But even the critics who were warmest toward that season often complained about how it necessarily had to shift focus to the royals who weren’t Elizabeth. It’s what the series had to do to survive — just like Mad Men had to move beyond Don Draper and Breaking Bad had to move beyond Walter White — but in this case, it only underlined how much the series struggles to tell stories about characters who aren’t Elizabeth. (I hear you, Princess Margaret stans, and I disagree, though Vanessa Kirby is wonderful.)

Meanwhile, The Handmaid’s Tale was largely effective at retrofitting itself into a twisted family drama in its second season, pivoting around the interactions of characters within the Waterford house. But that simultaneously painted the show into a high-concept corner: For The Handmaid’s Tale to continue past season two without breaking its core premise, it will need to radically overturn its status quo, but to continue being a TV show, it will need to get its protagonist back to the place where most of the other characters reside.

(If there’s a sign that Handmaid’s has found a way to navigate this tricky situation, it’s the way it built up the characters of Serena Joy and Emily into secondary protagonists in season two, suggesting they might carry more of the storytelling load in season three, allowing June to enter a new phase of her own story. But that move is far from a guarantee of future success.)

But The Crown’s and The Handmaid’s Tale’s fellow second-season Emmy nominees simply seemed to chase their own tails. I preferred Stranger Things’ second season to its first, but its attempts to expand a paper-thin world ended up mostly falling flat. And both This Is Us and Westworld followed their puzzle structures into a spiral of oblivion.

This is why a less-than-splashy first season is sometimes an asset to a series, if it can find enough dedicated viewers to get to season two. By that point, the simple act of expanding a premise into a TV show can feel revolutionary. When Halt and Catch Fire deepened its ensemble of characters in year two, or when The Americans focused more on its family relationships, or when The Leftovers shifted to become much more character-centric than it had been before, it could feel like all of these shows were responding to criticisms of their first years. And maybe that was true, but they were also just doing what any TV show needs to do to run for ages to come.

Now, a disappointing second season isn’t an absolute guarantor of doom. The second seasons of shows as diverse as Homeland, Game of Thrones, Lost, and even The Sopranos riled up some in their fan bases with how they failed to capitalize on the promise of season one, and I would argue that all of those series found their way back to making good television, and even great television in the case of the latter two (where in both cases, I would say the show’s best season was its fifth). But a disappointing second season does tend to put a show on notice with its audience, which can far too often lead to minor missteps getting overinflated into series-ending catastrophes, at least in the minds of fans.

All of this makes me think that the age of streaming, which rewards shows that launch right out of the gate with big, flashy ideas at their core, may be detrimental to dramas that are constructed for the long haul. When a show lives or dies by buzz and social media chatter, it’s a lot harder for a second season that does the painstaking work of expanding a premise into a TV show to evoke the same kind of excitement and wonder — especially if you’re watching it all in one big binge, feeling a sinking sense of, “Do I like this show as much as I once did?”

And yet that work is usually necessary. Creating great TV is about artistic expression, sure, but it’s frequently also about very boring craftsmanship things, like knowing how to ignore the hype and just focus on what makes TV work.

After all, I haven’t touched on TV comedy at all in this article, and that’s a genre built deliberately to usually embrace low-concept, somewhat repetitive premises that can run, theoretically, forever. And if TV drama seems to be in an era when it’s struggling, TV comedy is thriving, perhaps because it knows that good TV is sometimes found in places that are just a little unexciting. A disappointing second season is crushing in the moment, but sometimes, you’ll find it’s just what a show needed to be able to keep going.

Author: Todd VanDerWerff

Read More