The original game of Life was depressing. Really depressing.

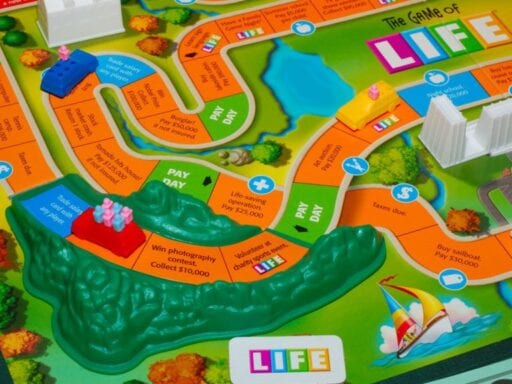

When we think of the game of Life, the candy-colored 1950s and ’60s version comes to mind — featuring the glossy American dream of buying a house, piling kids in the car, and becoming a millionaire.

But it wasn’t always that way. The game of Life is more than 150 years old, and its early incarnations were very, very different. The goal wasn’t to be a millionaire, but simply to live a good life. And that included the risk of suffering some incredibly depressing consequences — like suicide or poverty:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3347200/lifesquares_revised.0.jpg)

(Joss Fong/Vox)

Why did the early game of Life feature the chance of utter ruin alongside high-minded goals like honesty, perseverance, and industry? Why was it so depressing? And how did a game about values transform into one about getting rich? The answer is rooted in the unusual and fantastic passions of the game’s inventor, a man named Milton Bradley.

How Milton Bradley made Life — after screwing up Lincoln’s portrait

Born in 1836 in Maine, Milton Bradley grew up in Lowell, Massachusetts, where he dropped out of college to begin a career in the printing business. He quickly acquired a monopoly — he owned one of the only lithography machines in Massachusetts outside of Boston — and it made him a wild success.

But in 1860, disaster struck. Bradley had printed thousands of portraits of Abraham Lincoln, hoping for strong sales based on Lincoln’s presidential nomination. Unfortunately, Lincoln grew a beard in the meantime, and the portraits failed to sell, nearly bankrupting Bradley.

From that failure, however, his greatest success was born. Soon thereafter, Bradley invented the Checkered Game of Life, with the game’s board mirroring the ups and downs of his own career. It turned out to be a hit. By 1861, he’d sold 45,000 copies of the game and was bundling it into a popular game pack for Civil War soldiers. In 1866, Bradley patented the game and secured his fortune.

Bradley, along with his collaborator George Tapley, had become a hitmaker. But the unusual success of the Checkered Game of Life was due to Bradley’s unique obsessions. That simple game would fund his true passion.

Milton Bradley was an educator with a deeply moral bent

“Bradley was very much a product of his day,” Jennifer Snyder says. She’s an assistant professor of art education at Austin Peay State University, and she wrote her dissertation about Bradley’s unique life. “He was a very religious man … he seemed very interesting, but in some ways probably pretty rigid in terms of his view of what was appropriate or not.”

Snyder says Bradley’s interest in games came out of his experience as a printmaker, but he also incorporated his other passions: education and the quest to live a virtuous life.

Bradley was a follower of Friedrich Froebel, a German educator generally credited with inventing kindergarten. Froebel’s innovations included Froebel Gifts, play materials that helped children learn. Bradley also attended lectures by Elizabeth Peabody, who developed the first English-speaking kindergarten in 1860 (Bradley was such a fan that his company published her portrait). Snyder believes Bradley’s background in early education led him to make games that, like the Froebel Gifts, could help people learn through play.

“Everything Milton Bradley published had a really strong moral tone to it when he was still in charge of the company,” Snyder says. “He viewed everything as an educational opportunity. It was an opportunity for people to be educated in the way he thought they should be. The game of Life is very much about taking the moral high road and walking the appropriate path.”

That philosophy lent the game of Life a dual purpose: moneymaker and vehicle for moral instruction. Often, the money from Life even fueled other educational ventures, like the production of teacher supplies and educational materials.

The moral backstory behind the game of Life spinner

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3347298/5383123233_8754630b66_b.0.jpg)

The game of Life spinner. (John Liu)

Ever wonder why the game of Life has a spinner?

“Milton Bradley didn’t believe in dice, because dice were associated with gambling,” Snyder says. “And gambling was bad.” As an alternative, Bradley developed a spinner — though the original device was a top-like spinner called a teetotum.

Bradley’s morals were deeply embedded in the original game of Life in other ways, too. Unlike later versions, the original game didn’t have money — it relied instead on points on squares to calculate the winner. The goal wasn’t a fat retirement fund, but rather “happy old age.” Those who achieved it did so through industrious living (and by playing the game prudently).

An early brochure for the game claimed that “it is only by constant and renewed exertion that lost ground can be regained.” And victory was obtained by being appropriate — not by gaining cash. That meant players had to run the risk of landing on depressing squares, like suicide, that showed the consequences of playing Life (and living life) the wrong way. If you hit the suicide square, you were thrown out of the game.

“Milton Bradley envisioned happy old age as the goal of the game of Life,” Snyder says. “It was much more moral in its original interpretation.”

When Bradley’s life ended, so did his meaning of Life

After Milton Bradley died in 1911, the game of Life began to transform from board-game-as-moral-tract to board-game-as-escape. The version familiar to modern players makes success all about money and achievement rather than virtue (as Vox’s Danielle Kurtzleben notes, it is a reflection of a more materialistic American dream). That shift may be inevitable for a board game that’s meant to be played and forgotten. A game without suicide squares, intemperance, and ruin is less shocking than Milton Bradley’s Checkered Game of Life, but the removal of those squares also erased Bradley’s moral vision for Life in favor of escapism and cash.

That makes a couple of questions surprisingly tricky to answer: what should the meaning of Life be? And which version of the game is actually more depressing?

Author: Phil Edwards

Read More

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3347238/bradleyslincoln.0.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3347306/miltonbradley.0.jpg)