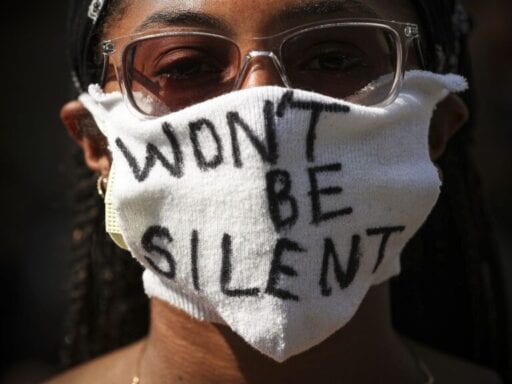

There have been uprisings against police brutality and racism before, but this is the country at its exasperation point.

Americans have come out nightly in nearly every US city to demonstrate for the past week. They’ve been attacked by police, tear-gassed, and arrested, and have marched shoulder to shoulder amid a deadly pandemic. Their demand: an end to racism, police brutality, and the attitudes and policies that allow both to exist.

We have seen uprisings over racism and police brutality before, the most famous being the civil rights movement of the 1960s. There was sometimes a sense that those uprisings had brought on a great deal of progress in a short period and that the eradication of systemic racism would be a long-term project from then on out, with incremental changes ensuring the arc of the moral universe bent toward justice. The recent protest movement — though nascent — seems to reject that idea. The protesters want change now.

And it is easy to see why: Systemic racism takes a physical, existential toll on communities of color.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20018176/GettyImages_1216502237.jpg) Jim Vondruska/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Jim Vondruska/NurPhoto via Getty Images/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20018177/GettyImages_1217489655.jpg) Olivier Douliery/AFP via Getty Images

Olivier Douliery/AFP via Getty Images/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20018179/GettyImages_1233825125.jpg) Scott Olson/Getty Images

Scott Olson/Getty ImagesThere is the police violence itself — most recently, against George Floyd, an unarmed black man who died after a white police officer pinned him down by the neck with his knee for nearly nine minutes. Among Floyd’s final words were “I can’t breathe,” mirroring the last moments of Eric Garner, another unarmed black man who died after a white police officer squeezed his neck for 15 seconds in 2014.

Floyd’s killing followed the killing of Breonna Taylor by police in her own home, the shooting of Sean Reed in Indiana, the shooting of Tony McDade in Florida, and the extrajudicial killing of Ahmaud Arbery by a white father and son, the former a retired police detective, now charged with murder and aggravated assault.

Beyond the recent spate of police killings, there is, of course, Covid-19, a disease that has disproportionately taken black and Latinx lives and has had negative economic effects on black and Latinx workers. Environmental factors exacerbated by segregation (like heavily polluted air or water full of lead), health conditions created by those environmental factors (like heart disease, hypertension, and asthma), and constant stressors like the threat posed by police are contributing to poor health outcomes — outcomes that leave black Americans more susceptible to Covid-19.

Add to that economic losses: Disinvestment in black and Latinx communities as well as inequities in education, transportation, and opportunity have led black and Latinx Americans to bear an unequal share of pay cuts and job losses.

There is also a regression in policy that has stemmed from the country’s leadership. Policies instituted to protect black lives have been systematically rolled back in recent years, from the return of mandatory minimum sentences to the Department of Justice refusing to conduct oversight of police departments accused of civil rights violations and President Donald Trump signing an executive order once again allowing police easy access to military equipment.

The realities of illness, unemployment, polluted air and water, unequal access to education, and mass incarceration — compounded with the fear of being killed by one of your fellow Americans or by a mysterious and still unchecked disease — has life feeling particularly fragile and the world particularly dire. Many are fed up. They need to direct their rage. They cannot live and suffer any longer as they once felt they had to.

The protesters are fighting against history, present injustices, and hearts that refuse to be changed

At the core of this rage is a legitimate fear for black Americans: the sense that they can be killed anywhere at any time by anyone, but especially by law enforcement. It is a feeling black Americans have carried for all of America’s history. And the fact that the feeling has persisted for so long, that it has passed through so many iterations — the casual and common brutality of slavery, the lynching terrorism that followed, the assassinations of the civil rights era, the police killings of today — has created a feeling of futility. That no effort, no matter how herculean — not marching a million people through the nation’s capital, not placing a black man at the head of government — will be enough.

This sort of frustration can only build so long before it becomes anger. And it has.

Americans have left their homes where they were told to shelter in place for safety to express that anger, to rage in the ways that feel right to them — chanting, marching, rattling barricades, seizing goods, writing on walls, creating art, climbing vehicles, breaking glass, setting fires.

They have done so in masses that reflected the diversity of the country they hope will change, a positive development given racism and police brutality aren’t a problem black people have that they need support to solve; they are evils black people suffer with little control over — ills that can be destroyed only with the assistance of all those who make up society and those who consciously or unconsciously benefit from and perpetuate them.

In doing this, in acknowledging this, these protesters have begun to create a new movement — one that aims to rework society.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20018204/GettyImages_1242649150.jpg) Ira L. Black/Corbis via Getty Images

Ira L. Black/Corbis via Getty ImagesThe breadth and weight of what protesters are fighting for is why they are not slowing down. In Ferguson’s 2014 uprisings, the unrest quieted when Michael Brown’s family requested people not protest on the day of his funeral. In Baltimore, protests dissipated in 2015 when charges were brought against the officers in Freddie Gray’s death. When charges were brought against former police officer Derek Chauvin — who has been charged with Floyd’s murder — on Friday, protests only ramped up. In fact, there were protests in cities from Atlanta to Chicago to San Diego only hours later. Over the weekend, despite nearly 20 percent of US citizens being under a curfew, people still took to the streets.

And those demonstrations happened not just in big cities but in towns and villages across the country, including ones that do not necessarily have large black populations: they happened in Normal, Illinois, and Laramie, Wyoming; Naples, Florida, and Bend, Oregon; and countless other places. These protests are a reminder that policing, systemic racism, and the legacy of slavery do not just affect cities and do not just affect black people — that there is something very wrong with American society, all of it, everywhere, and that people across the nation want something new.

Because of this, protesters are demanding life itself be changed — that policing be fairer and kinder, that biases be inspected and corrected, that lasting policies be implemented that erase inequality, and that all people be able to move through the country without experiencing existential dread.

President Trump’s policies have moved the US further from these goals. His rhetoric has been unhelpful as well, and his divisive words about the protests have been indicative of the divide between the protesters and what they are protesting.

He has encouraged law enforcement — celebrating their most aggressive tactics and tweeting that protesters who get too close to the White House would be met “vicious dogs” and “ominous weapons.” He has quoted segregationists in making further threats, ones he later tried to claim were not meant to be threatening at all.

Rather than make any attempt to engage with the protesters or understand their demands, Trump has accused them of representing the “depravity of the Radical Left,” and of being “looters and thugs,” while using his Twitter account to highlight the activities of agitators, promote increased National Guard deployments, and call for “LAW & ORDER!”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20018220/GettyImages_1216828184.jpg) Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images

Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20018221/GettyImages_1216828159.jpg) Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images

Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty ImagesBut perhaps the most illustrative example of how Trump typifies this divide is the manner in which George Floyd’s brother Philonise Floyd described a call he had with the president.

“He didn’t give me an opportunity to even speak,” Floyd said on MSNBC. “It was hard. I was trying to talk to him, but he just kept, like, pushing me off, like, ‘I don’t want to hear what you’re talking about.’”

This is what the protests are pushing back against: a sense that many in power do not see the problem and do not want to hear it described — that despite so many shouts for change, no one who can make those changes is listening, be they policymakers or individuals with biases they won’t acknowledge, let alone address.

And whether the protests will make them listen is not yet clear.

Recent protests have brought limited change. Demonstrators hope this time will be different.

With the feeling of shouting into a void comes a hopelessness that has led to debate over the worth, effectiveness, and viability of the protests.

There have been many protests against police killing unarmed black men in recent years, some of which have gone on for weeks, like the 2017 St. Louis protests over the killing of Anthony Lamar Smith by former police officer Jason Stockley, and, of course, Ferguson. Out of those protests have come the Black Lives Matter movement, other advocacy initiatives, and even some changes to police department policies.

But the data shows that black lives continue to be taken, including by police who often face few to no consequences for doing so.

A recent analysis by the advocacy group Mapping Police Violence found that 99 percent of police killings from 2013 to 2019 did not result in officers even being charged with a crime. A recent study by researchers at Rutgers University, the University of Michigan, and Washington University in St. Louis — explained by my colleague Dylan Scott — found black men have a 1 in 1,000 chance of being killed by police.

Statistics like these have led to questions over whether these latest protests can foster a change earlier demonstrations did not, and — as lawmakers of all ethnicities condemn the more aggressive approaches some have embraced, like setting fires and seizing property — whether some escalation in tactics would be wise.

Many, as Nikole Hannah-Jones of the New York Times did in a thread on Twitter, have argued that past protests that brought about change have involved violence, and that even the nonviolent protests of the 1960s relied on black Americans inviting violence to make their point:

Peaceful protest did not bring about the great civil rights legislation of the 1960s. Black people being firebombed, water-hosed, lynched, bitten by dogs, beaten to a pulp by police trying to march across a bridge is what brought the changes. Violence.

— Ida Bae Wells (@nhannahjones) May 29, 2020

Those protests, Hannah-Jones wrote, showed that “Black Americans must *absorb* white violence in order to benefit from white sympathy. At some point, communities say no and face the consequences.”

Others, like Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, have called for more measured protests; after property was damaged across the city, Bottoms said, “This is not a protest. This is not in the spirit of Martin Luther King, Jr. This is chaos.”

This tension exists among those out in the streets as well, as captured in a video that has gone viral, featuring two men discussing the protests:

Damm this is deep #blacklivesmatter pic.twitter.com/G3NzgyMxHK

— BlackCultureEntertainment (@4TheCulture____) May 31, 2020

It is a debate that has yet to be settled, and one that ties into another ongoing question about the protests: If no change comes, will they be sustained, or will they dissipate in the next few weeks, or even days?

On one hand, one of the things the protests are against — police brutality — has been a prominent feature of the demonstrations so far. Police and the National Guard, with the aid of military equipment, have left protesters and observers bloodied. They have been recorded pulling people from cars and throwing bystanders, including elderly ones, to the ground. Being confronted so directly with what they are protesting would seem to give demonstrators more reasons to continue their uprisings.

And given their broad scope, one conviction or arrest won’t calm anyone’s anger. Much has also been made of the demographics of crowds, of peaceful white protesters and of white agitators — a larger coalition would seem to be more self-sustaining than a smaller one.

On the other hand, however, it is not clear how long protesters will be willing to continue their demonstrations if nothing moves forward — if the officers involved with Floyd’s death are not convicted, if Breonna Taylor’s killer goes free, if the government continues its escalations of force, and if deaths like Floyd’s and Taylor’s and Reed’s continue.

This is clearly an important point in time, and one arrived at after decades of trauma. But we will have to wait and see if this is the point at which change actually happens.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20018233/GettyImages_1216238900_3.08.04_PM.jpg) Neal Waters/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Neal Waters/Anadolu Agency via Getty ImagesSupport Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Sean Collins

Read More