Our roundtable discusses the Oscar chances for the director’s twisty elegy for a lost age.

Every year, between five and 10 movies compete for the Oscars’ Best Picture trophy. It’s the most prestigious award that the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences gives out every year, announced right at the end of the ceremony. And there aren’t any set rules about what constitutes a “best” picture. It’s the movie — for better or worse, depending on the year — that Hollywood designates as its standard bearer for the current moment.

And so, the film that wins Best Picture essentially represents the American movie industry’s view of its accomplishments in the present and its aspirations for the future.

Each year’s nominee slate roughly approximates the movies the industry thinks showcase its greatest achievements from the past 12 months. And one thing that’s true about the nine Best Picture nominees from 2019 is that, in tone and theme, they’re all over the place.

The most-nominated film overall is also one of the year’s most successful commercially, and one of its most controversial. A beloved social thriller from Korea has reached the milestone of becoming that country’s first Best Picture and Best International Feature nominee. There are three historical dramas: one set during World War I, one that centers on a 1966 car race, and one that co-stars an imaginary Hitler. There’s a quietly funny drama about love and divorce and a revisionist history of Hollywood in the summer of 1969. The world’s arguably most influential living auteur made a gangster epic with eternity on its mind. And a critically acclaimed adaptation of a celebrated novel rounds out the group.

In the runup to the Oscars on February 9, the Vox staff is looking at each of the nine Best Picture nominees in turn. What makes this film appealing to Academy voters? What makes it emblematic of the year? And should it win?

Below, Vox critic at large Emily VanDerWerff, culture reporter Aja Romano, and film critic Alissa Wilkinson talk about Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Quentin Tarantino’s elegy to a lost age.

Alissa: I think Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is the movie-est of the movies nominated for Best Picture — not only does it feel and look like it’s from an earlier era, but it’s about Hollywood.

The Academy loves to nominate movies about itself, whether or not they’re any good. But in this case I think it’s totally merited. People have quibbled and quarreled with this movie, as they do with all of Quentin Tarantino’s work. Usually I’m not much of a fan. But what you (and I) cannot possibly deny is that Tarantino is an obsessive, exacting, thrilling director, and he sure knows what he wants.

And I think those characteristics are on full display in this movie. It’s an elegy and a romp, and because of its ending, which reimagines history, it narrowly escapes being a tragedy and becomes a comedy instead.

Plus it came out just in time to commemorate the tumultuous summer of ’69, when the Manson family was wreaking havoc on the nerves and in some case the lives of people living in Hollywood — a time that has since passed into myth. Why not turn myth into a fairy tale?

But the reactions have certainly been varied to the film. What did you think when you first saw it? And did you see the ending coming?

Aja: I want to preface everything I say about Once Upon a Time in Hollywood with the following story, which is that when I went to see it, there was a man sitting in front of me who was constantly, obsessively, very distractedly (and distractingly) checking his phone for the first 15 minutes of the film. And because I am That Person, I asked him to turn it off. I always do this in movie theaters if it’s a big problem, and nearly always when I do this, what happens is that the person puts their phone away, fidgets for about 20 minutes, and then digs it out again. That’s what I expected to happen at Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, and I was bracing for the movie to be intercut with constant glimpses of this man’s Insta feed.

But instead, I got wrapped up in the film, and when I glanced back at the man a while later, I realized that he was staring at the movie screen, completely rapt and still, like he’d never seen a movie before. And he stayed that that way. Our theater was as quiet and ensorcelled as a church. It was a wondrous little moment, and to me it was entirely a testament to Tarantino’s obsessive commitment to telling a story through pure cinema.

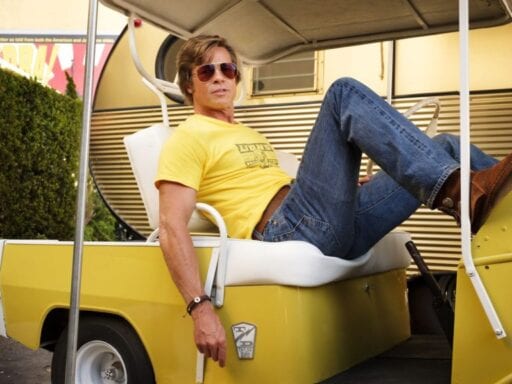

All those long quiet shots lingering on Brad Pitt’s face, or following cult members through the ranch, or walking down streets with Margot Robbie — it all worked to really sell the idea that Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is a fairy tale, and that Hollywood itself was once a fairy tale. The film honestly felt like a fairy tale — until it didn’t anymore, which was the whole point.

But I think I disagree with you about the film’s narrow escape into, uh, escapism. I think its horrifically, appallingly violent ending is as full a deconstruction of Hollywood violence as Tarantino has ever delivered, and I think it matters greatly that Tarantino chose to apply “the Hollywood ending” to the Manson story. The ending exposes the artifice of that type of narrative construction, because it so clearly and transparently sets itself up as a buffer between Hollywood and everything that Hollywood represents — power, fame, propaganda, its mythologized use of violence — and the real-world effects of the Hollywood machine, via the Manson murders.

I think this is a difficult film to read in many ways because Tarantino is so self-aware about his own gleeful paradoxes, and due to his habit of appropriating other people’s pain as an excuse for violent revenge fantasies. But after having sat with that ending all these months, I find myself seeing it as the most self-reflective, vulnerable, and fraught of all Tarantino’s attempts to reckon with his idols. (Even though, typically, I’m still completely turned off by the undercurrent of misogyny and valorization of violence in that climax. I can’t reconcile these things! I’m probably not supposed to! Gleeful paradox!)

Emily: I would never say I didn’t like Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, but I felt held at arm’s length by it for most of its running time, despite seeing it at the Arclight on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood. The Arclight was perhaps the ideal venue to see this particular film in, something I was especially aware of once I stepped out of the screening into a warm Los Angeles evening. (Indeed, the theater’s famous Cinerama Dome is actually featured in the film.) It was clear that something magical was happening in this movie; it just wasn’t clear if I was invited to be a part of it.

I found the assortment of controversies that attached themselves to Once Upon a Time in Hollywood to be mildly overblown, but I think they all center on precisely what made me feel distanced from it: No matter how you shake it, there’s not a ton of room in Quentin Tarantino’s Hollywood for anybody who’s not a straight, cisgender, white man.

I want to be clear that, uh, this was true of the real Hollywood in 1969, too. Tarantino’s love of revisionist history doesn’t extend to having, say, Uma Thurman and Pam Grier (two of his former collaborators) play Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’s two lead characters who fuck up some Mansonites in the end. I also want to be clear that I don’t think he should’ve done this, or felt like he needed to. His choice to center this story on two has-beens clinging by their fingernails to hold onto their position in Hollywood’s social hierarchy is a poignant one, and it adds to much of the movie’s glorious recreation of the feel of that period. (Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, if nothing else, is a triumph of mood, and I dearly wish there was a music supervision Oscar it could win for that amazing collection of tunes it employed.)

But the movie’s longing for 1969 Hollywood was so strong that its repudiation of same — if you can call it a repudiation — could never overcome the hypnotic sense I had of time falling away from me and being transported back to some other place. And I felt acutely aware at all times that there wasn’t a ton of space for a trans woman (or maybe just a woman!) like me in 1969 Hollywood. If Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is a party (and a lot of it is), I felt like I was outside, hearing the droning music but unable to distinguish the tune.

That said, I love the ending conceptually while remaining unsettled by its execution. Its ultra-violence rubbed me the wrong way, but also seemed so crucial to Tarantino’s central point about how the movies feed off of human prurience. It’s one of the most audacious things I’ve seen in a movie in recent memory. I don’t know how I feel about it.

I guess that last sentence might be my entire review of this film in a nutshell.

Alissa: To be clear, what I mean when I say that Once Upon a Time in Hollywood becomes a comedy is that the film is structured like a comedy — which, as you’ve noted, Aja, has a grander purpose than just “being a comedy,” whatever that means. Comedy reaches its greatest heights when it jabs at absurdity and ridicules unjust realities, and that’s just what Tarantino delights in doing, when he’s doing his best work.

Given Emily’s response to the film, then, let’s talk about the role of Sharon Tate (played by Margot Robbie). Controversy erupted over whether the character has enough to do, based primarily on the relatively few number of lines she gets to say out loud. (A similar charge came up in the case of another Best Picture nominee, regarding Anna Paquin’s role in The Irishman.) I don’t think that complaint was warranted, because acting, after all, is not just about lines; it’s about a performer embodies a character. But I want to hear what you think.

Are there merits to the argument that Tate was minimized? What are that argument’s weaknesses?

Aja: Once Upon a Time is very transparent about using Sharon Tate as a symbol of Old Hollywood glamour at its most alluring and unapproachable. Perhaps the film shouldn’t have used her that way, and Tarantino should have wanted her to be more active. I think that’s an argument worth listening to, but I also think it doesn’t acknowledge that in her own life, Sharon Tate was explicitly marketed as a symbol of unapproachable Hollywood glamour.

In a 1965 short documentary, All Eyes On Sharon Tate, she’s shown jet-setting around Europe and hobnobbing with Deborah Kerr in a literal castle. Every fairy tale comes with a princess in a castle at its center, and even though they descend from their ivory tower — as Tate memorably does in Tarantino’s film — we never for a moment forget that they’re princesses.

What’s mystifying and a lot more troubling to me is how little the film makes an effort to really understand the Manson girls. There’s something about them that’s otherworldly and even more removed and inaccessible than Sharon Tate herself. All of these women, including Tate, had their youth and beauty exploited when they were still teenagers, but there’s no sense in Tarantino’s narrative that a commonality might lie between them, or that the Manson girls, abused and brainwashed by a serial sexual predator, were also victims, not monsters.

Since we see them primarily through the eyes of Brad Pitt’s character, it might be reasonable to assume that we’re meant to interpret that opacity as a reflection of his inability to see these women as people. But Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’s overall tone undermines that viewpoint, to me; it seems to observe its women through the wrong end of a telescope because it just doesn’t know what else to do with them — while quietly despairing over that fact as a part of its attempt to simultaneously eulogize and deconstruct its own mythos.

Emily: Right. When I saw this movie, I found the mild uproar over how little Sharon Tate speaks to be wildly overblown. Sure, she’s a symbol more than a character, but she’s not denied her humanity. It’s clear she’s a symbol because of what she represents, and everybody within the film has a different feeling about what she represents. That extends to Tarantino even! If Sharon Tate were a more grounded presence, instead of someone ethereal, Once Upon a Time would be a different movie. And I’m not sure I want Quentin Tarantino, of all people, writing and directing that movie.

But I also agree with you, Aja, that the Manson girls are presented in a way I’m still wrestling with literally months after seeing the film. (One might argue that this is a sign of its power!) The paradox of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is that it creates an immersive experience for viewers to step into — but it also loves to remind us, at all times, that we’re watching a movie. It creates a split inside the viewer that Tarantino exploits ruthlessly.

So when I saw the film and Brad Pitt threw a can of dog food into a woman’s face — a legitimately shocking moment — and the man sitting right next to me started cheering loudly and lustily, that response yanked me right out of the movie. I obviously don’t blame the film for this, as nobody involved in any film can control for how viewers watch it. But I did feel discomfited by the way that Once Upon a Time in Hollywood kept playing fast and loose with the idea that those young women could be treated as punching bags because, historically, they murdered several people.

I don’t want to downplay the fact that they murdered several people, either. Those women (and the man who was with them) murdered several people, horrifically. But they were also brainwashed by a cult leader. They had their agency stripped from them on some level, and while their crimes deserve punishment both in our reality and the movie’s reality, I’m not sure Hollywood has thought about them beyond “those Manson girls.”

Or maybe it has? Margaret Qualley’s turn as a different kind of Manson cult member is one of my favorite performances in the whole movie, and Tarantino seems to be playing around with the idea that violence — even fictional movie violence — only ever begets more violence. But he also seems to playing around with the idea that maybe the only solution to violence is more violence, even when the violence is … fictional movie violence.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is, in a weird way, an old man movie. At 56, Tarantino is well into middle age now, and he’s about to have his first child. This film is a story told by someone who feels time slipping through his fingers but also someone who understands all of the contradictions inherent in the past he longs for. It upset me deeply; that was also its intention.

Alissa: Margaret Qualley should be in more movies, is my take.

Last question: Since we’ve all done a lot of reading and thinking on the period of time that is covered in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, what would you recommend to someone who wanted to find out what actually happened that night, or what it felt like to live in Hollywood during the summer of 1969? Personally, I think Joan Didion’s “The White Album” essay may be the best way to get the feeling of the time. What else would you suggest?

Aja: I’ve written previously for Vox about how much I love Karina Longworth’s You Must Remember Manson, which was originally a single season of her podcast about vintage Hollywood, You Must Remember This, that she broke out as a standalone podcast after Charles Manson’s death in 2017. It’s one of the best and fullest pictures of not only the Manson family but the world they inhabited — a world that encompassed everything from members of the Manson family starring in counterculture cult films to a music producer moving out of his girlfriend’s house on Cielo Drive because his mom was nervous about Charles Manson, and did we mention his mom was Doris Day?

Longworth never loses sight of the stark contrast between the abject poverty the cult was battling and their surreal brushes with Hollywood royalty. And she especially never loses sight of the fact that Manson himself was a ruthless sexual predator — he learned how to be a pimp in prison — and that the young, abused women of Manson’s cult were Manson victims, too.

Emily: Honestly, I would just watch movies from that period. If there’s one thing Tarantino captures perfectly in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, it’s a sense of something winding down, but no one quite feeling confident about what might take its place.

The late ’60s and early ’70s in Hollywood were a period when the gigantic, bloated mega-movies that reigned in the late ’50s and early ’60s were waning in influence, but everybody kept making them. Movies like Doctor Dolittle and Hello Dolly were huge flops. And yet rising up alongside them were bold new visions of what moviemaking could be, films like Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate, which embraced a youth culture that Hollywood was a little reticent to fully hop on board with. Those new visions changed the industry, but everything could have been different.

And even if it wasn’t, the kinds of B pictures that Rick Dalton represents eventually got invited inside Hollywood’s big tent nevertheless. When Rick is welcomed into Sharon Tate’s home in the last shot of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, the scene is presented as a triumph. And yet the old school Hollywood the film revels in eventually gave way to blockbuster Hollywood, where the goofy, low-budget serials became the basis of movies like Jaws and Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark. The Hollywood we know today might not be the kind of place where a Rick Dalton can thrive, but it’s Rick Dalton’s Hollywood nevertheless.

He eventually got invited in. It just took a while.

Author: Alissa Wilkinson

Read More