Some Supreme Court justices just want to watch the world burn.

On Thursday, the Supreme Court imposed strict new limits on the Clean Water Act. The Court’s decision in Sackett v. EPA is likely to do serious harm to the government’s ability to quell water pollution, including in major waterways such as the Mississippi River and the Chesapeake Bay.

Meanwhile, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a concurring opinion that would so severely limit Congress’s power to legislate that he might as well have taken several volumes of the United States Code and lit them on fire.

To be clear, a concurring opinion is not the law — it merely reflects the views of the justices who sign onto it. And this particular opinion is unlikely to garner five votes to become law unless the Court’s membership changes drastically. But that does not change the fact that Thomas (and Gorsuch, who joined his opinion) is one of only nine justices, and their views tend to shape the ideas of lawyers and judges throughout the legal system.

Under the approach Thomas lays out in his Sackett concurrence, the federal ban on child labor is unconstitutional. So is the minimum wage, federal laws protecting the right to unionize, bans on workplace discrimination, and nearly all other regulation of the workplace. Thomas’s approach endangers countless laws governing private business, from rules requiring health insurers to cover people with preexisting conditions to the ban on whites-only lunch counters. And even that is underselling just how much law would be snuffed out if Thomas’s approach took hold.

Though Thomas has said similar things in the past, his opinion in Sackett is one of the most nihilistic opinions written by any federal judge in the last nine decades. This opinion is particularly notable, moreover, because it is joined by another justice, Neil Gorsuch. Gorsuch, who was appointed to the Court in 2017, had not previously revealed just how far he is willing to go in sabotaging the United States government.

That means that there are now at least two votes on the Supreme Court for an act of judicial arson unlike any in US history.

Much of Thomas’s opinion is an attack on what he calls the “New Deal era conceptions of Congress’ commerce power.” Thomas argues that the Court should return to the narrow understanding of Congress’s power to regulate the national economy that it followed in Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918), an infamous and long-ago-overruled decision striking down a law that prohibited goods produced by child laborers from being sold in US markets.

Then he goes even further than that. The primary thrust of his opinion is that the federal government’s authority over the “channels of interstate commerce” — roads, waterways, railroads, and other such infrastructure where people and goods can travel across state lines — is limited only to the power to “keep them open and free from any obstruction to their navigation.”

Taken seriously, this approach could gut much of the rest of the Clean Water Act, and allow a chemical company to dump countless tons of a deadly poison into the Mississippi River, so long as that poison did not prevent ships from traveling along the river.

It is worth emphasizing that, at least for the moment, only two of the Supreme Court’s nine members have signed onto this plan. There is probably little risk that Thomas and Gorsuch will get their way anytime soon — although it is also worth emphasizing that former President Donald Trump got to appoint three Supreme Court justices during his single term in office, so the Court’s center of gravity can lurch sharply to the right in a very short period of time.

But the fact remains that two of the most powerful people in the country — de facto philosopher kings who serve for life and who cannot be removed from office except by impeachment — have so little regard for the people of the United States that they would wipe away many of the foundations of our modern society and scoff at the consequences.

A brief history of the Constitution’s Commerce Clause

The Constitution permits Congress to enact laws regulating “Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes.” This is the primary constitutional provision giving the federal government authority over private businesses — including its ability to ban discrimination, to protect workers from exploitation by their employers, and to protect the environment.

The question of just how much power Congress has over private industry, however, has historically been one of the most contentious questions in US constitutional law, in large part because the society that Americans live in today would be unrecognizable to the people who drafted the original Constitution.

In the pre-industrial United States, most business took place in local marketplaces that had minimal interaction with the economies of other states. A farmer in Iowa would grow their grain on Iowan land, sell it to other Iowans, and rarely compete with other farmers in other states. Certainly, there were merchants engaged in interstate and international trade in the early days of the United States, and the Constitution was written to allow Congress to regulate these larger markets. But in early America there was a meaningful distinction between local and national marketplaces.

This atomized economy disappeared after the United States built a network of railroads allowing goods produced anywhere in the country to be sold in many different states. Suddenly, that same Iowa farmer’s grain would be shipped to Chicago via railway, where it would be intermingled with grain grown on farms across the Midwest. Then it might be sold to consumers in New York or Virginia or even somewhere overseas.

This history matters because the Constitution’s Commerce Clause only permits Congress to regulate domestic commerce “among the several States” — or, as one earlier Supreme Court decision put it, to regulate “commerce which concerns more States than one.”

In pre-industrial America, most business transactions concerned only one state, so they were beyond the federal government’s authority. But in a modern, industrialized economy, there is no such thing as a purely local marketplace. Businesses routinely trade across state lines. And even if one individual merchant only sells their goods to local consumers, that merchant still must compete with goods produced throughout the country and sell those goods at a price that is competitive in such a marketplace.

And so the same Commerce Clause that the framers of the Constitution drafted in the belief that it would give Congress only a limited power to regulate a small segment of US business, became a much broader power to regulate virtually any business transaction in the United States.

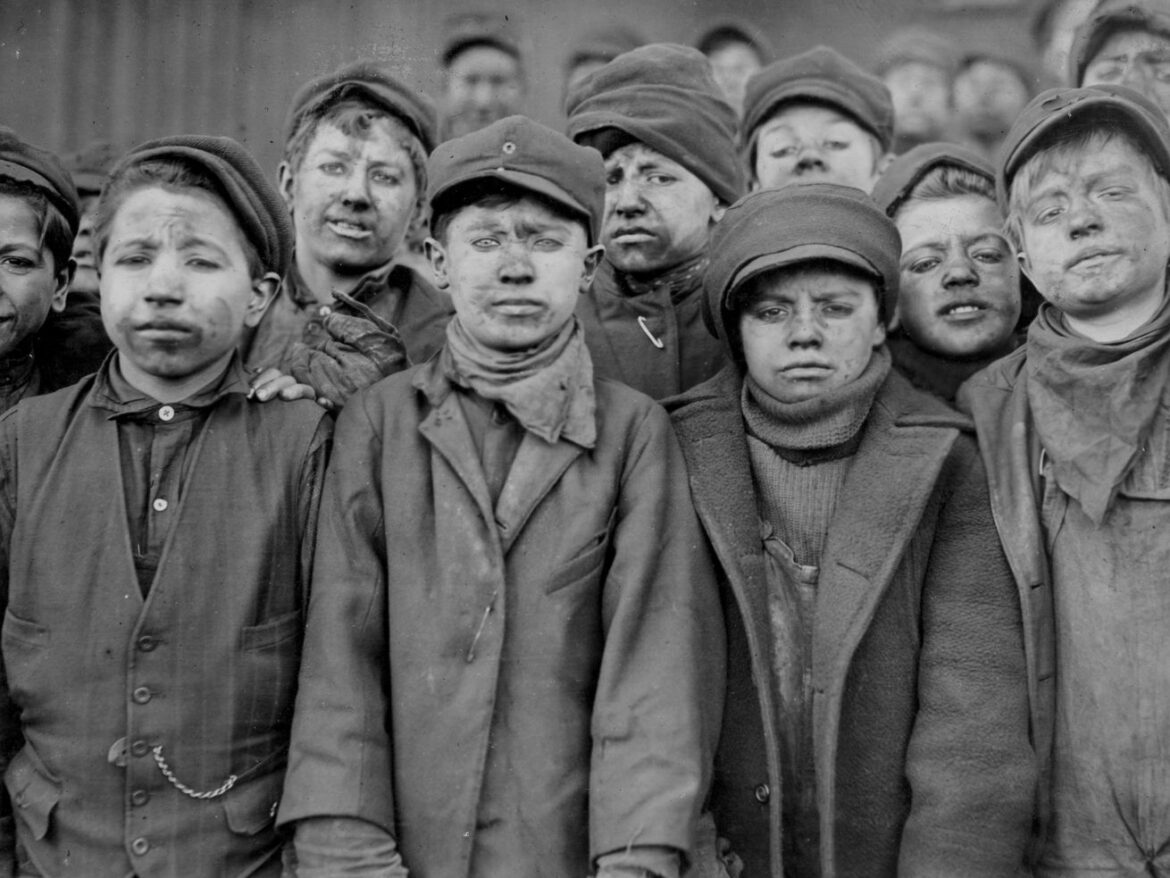

Needless to say, this expansion of federal power — an expansion that is entirely consistent with the Constitution’s text, even if it defied the framers’ expectations about that text’s implications — did not sit well with late 19th- and early 20th-century industrialists. They did not want to pay their workers a minimum wage set by Congress, nor stop hiring 6-year-old children to work in their cotton mills.

And so, beginning in the late 19th century, they convinced the Supreme Court to impose a series of increasingly arbitrary limits on Congress’s power to regulate commercial activity. These are the same arbitrary limits — limits that the Supreme Court abandoned in the 1930s — that Thomas and Gorsuch want to bring back.

Thomas and Gorsuch are literally arguing for the same rules that prohibited Congress from banning child labor

The high-water mark of the Court’s efforts to shield private business from federal regulation was Hammer v. Dagenhart, the 1918 decision striking down an effective federal ban on child labor.

Hammer reached this outcome by defining the word “commerce,” and with it Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce, very narrowly. “Commerce,” the Court said in Hammer, “includes the transportation of persons land property, as well as the purchase, sale and exchange of commodities.” It did not include “the making of goods.”

Thus, under Hammer, Congress could regulate the size of the railroad cars that shipped goods from cotton mills to local consumers. And it could regulate the actual sale of those goods. But it was powerless to enact laws governing the working conditions in factories where those goods were produced. It was powerless to ban child labor, except maybe in the limited circumstances where children were employed in shipping or sales.

Consider the distinction Hammer drew between production of goods and transit or sale of goods as you read this excerpt from Thomas’s Sackett opinion:

“The [Commerce] Clause’s text, structure, and history all indicate that, at the time of the founding, the term ‘commerce’ consisted of selling, buying, and bartering, as well as transporting for these purposes.” This meaning “stood in contrast to productive activities like manufacturing and agriculture.”

It’s the exact same argument! Thomas (and Gorsuch) are literally arguing that one of the Supreme Court’s most reviled decisions, a case that doomed a generation of children to hard labor for meager pay, was correctly decided — and that its rigid limits on federal regulation of private businesses should be imposed on the nation today.

There are many reasons why the Supreme Court eventually abandoned this distinction between transportation and sale (which Congress could regulate under Hammer) and the production of goods for sale (which Congress could not), but one of them is that it is a completely unworkable distinction. Even if Congress can’t forbid a factory from producing its goods using child labor, why can’t it use its authority over the transit and sale of goods to prohibit items produced by children from being sold or transported?

As the Supreme Court said in United States v. Darby (1941), which overruled Hammer, the Court’s child labor decision “cannot be reconciled with the conclusion which we have reached, that the power of Congress under the Commerce Clause is plenary to exclude any article from interstate commerce subject only to the specific prohibitions of the Constitution.” In other words, Congress is allowed to ban any product from interstate trade, and that includes any product that is produced using exploitative labor practices.

(The actual law at issue in Hammer technically did not ban child labor outright: It banned the transportation of goods produced by factories that employ children. So Hammer should have upheld that law as a valid exercise of Congress’s power to regulate transit of goods.)

Thomas’s Sackett opinion would place even stricter limits on the federal government’s authority over private industry than Hammer did. Thomas would not only restore Hammer’s distinction between transportation and production, he also claims that Congress’s authority over the “channels of interstate commerce” — that is, the very places where people and goods are transported from one location to another — is limited to a power to “keep them open and free from any obstruction to their navigation.”

This may be a direct response to Darby’s conclusion that Congress may “exclude any article from interstate commerce” and that it may use this power to effectively ban goods that are manufactured using unlawful labor practices. After all, if Congress’s power to regulate the transit of goods is limited to a power to keep roads, rivers, and railways free from obstruction, then it turns out that Congress cannot ban illegally manufactured goods after all. Checkmate, libs.

In any event, we have now gotten pretty deep into the theoretical underpinnings that allow the modern-day regulatory state to exist. The one important point to understand from this very technical conversation about US constitutional law is that decisions like Darby laid out the legal framework that makes it possible for the federal government to regulate private industry.

Countless laws — including anti-discrimination laws like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Americans with Disabilities Act, environmental laws like the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, and basic workplace regulations like Occupational Safety and Health Act, the minimum wage, or federal laws governing labor relations and unions — exist today because Hammer was overruled and the Supreme Court stopped placing arbitrary limits on the Commerce Clause.

And Thomas and Gorsuch would sweep all of this away.