They’re great for the fast food industry — but not so great for us.

Just outside St. Louis, in the inner-ring suburb of University City, there’s a little neighborhood often called the region’s unofficial Chinatown. Growing up in the area, it was one of my favorite places to be; reflective of the city’s diversity and vitality, it opened up the world to me. This past December, when I went home for the holidays, I discovered that what was once a beloved strip of immigrant- and minority-owned businesses there — a Korean grocery, a pho shop, a Jamaican joint with vegetarian options, a Black-owned barber shop — had been bulldozed and replaced by a double-lane drive-through Chick-fil-A.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25322849/Jeffrey_Plaza___ORIGINAL.jpeg)

Aubrey Byron for Vox

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25323240/Chick_fil_A_wide_view.jpg)

Aubrey Byron for Vox

Across the street, another strip was torn down to make way for a Raising Cane’s and a Chipotle, both also equipped with drive-throughs.

This part of town was never exactly the height of urban design; it had long been sprawly, car-oriented, and not great for walking. But the redevelopment gave it another character entirely. Before, the businesses there were destinations you could walk to if you wanted. Now, an enormous concrete retaining wall was built outside the Chick-fil-A, closing it off from sidewalk access like a fortress to fast food capitalism. The place had become so hostile to anyone outside a car that no one was going to get in there on foot. It was not a destination, but a place meant to be driven through — which is to say, no place at all.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25322857/Chick_fil_A_1.jpg)

Aubrey Byron for Vox

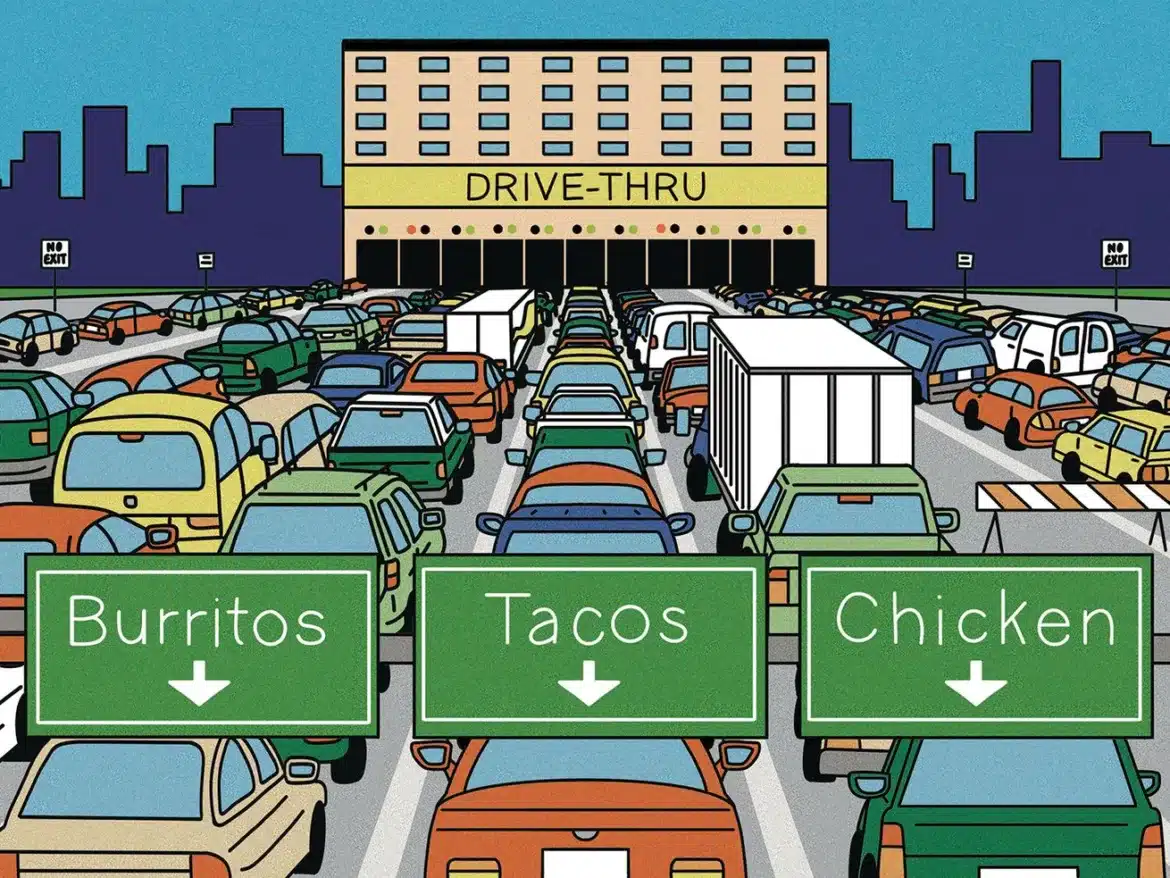

Although this particular city block had sentimental value to me, there’s nothing unique about what happened to it; it’s a pattern taking place across the country. Post-Covid, drive-throughs are proliferating among traditional fast food restaurants (Burger King, Taco Bell, KFC) as well as more upmarket brands not traditionally associated with that way of doing business, like Chipotle, Shake Shack, and Sweetgreen. Dining rooms are out and two-, three-, and even four-lane drive-throughs — mega drive-throughs — are in.

“Drive-throughs have been around a long time,” Charles Marohn, a former traffic engineer and well-known critic of America’s car-dependent urban planning, told me. Today, he said, “they’re becoming bigger and more obnoxious.”

That trend conflicts with a key objective that US cities are increasingly prioritizing: creating a safer, cleaner, walkable, livable urban environment that’s less dependent on cars. St. Louis and its suburbs, for example, in recent years have been building out bike lanes and walking and biking paths, including a segment that runs right up to the site of the new fried chicken and Chipotle drive-throughs. Where, exactly, are the people walking or biking that path supposed to go when they arrive at a development designed to be navigated only by car?

Drive-throughs, perhaps more than any other single building style, work against these livability goals. They worsen traffic congestion and release climate-warming air pollution from cars idling in line. They force cities to devote more land to asphalt, contributing to costly and unproductive sprawl. And they increase the chances of collisions with pedestrians and cyclists —in a country that already has one of the highest car crash death rates among peer countries — because they require cuts in the sidewalk to accommodate cars going in and out.

“Every time you have a curb cut, you’re creating an additional vehicle-pedestrian conflict point,” Minneapolis planning director Meg McMahan told Vox. “So there’s very real impacts to pedestrian safety.”

20 people showing up at a coffee shop by foot, bike, or transit, and it’s good business and place you might want to hang out. 20 people showing up by car and it’s a disaster, not a place you want to be, and will probably incite some road rage/frappuccino incident. pic.twitter.com/xuLWIGjgwq

— Maris Zivarts (@emveezee) November 23, 2021

On top of everything that’s already suboptimal about what urban planners call the American built environment, “the drive-through just kicks you in the nuts,” Marohn said. “It’s like, we’re going to actually add the added bonus that you can’t walk here at all because it’s really dangerous. … That’s what the drive-through does: It magnifies the negativity.”

Why the fast food industry loves drive-throughs

Drive-throughs have long made up a large volume of fast food businesses’ sales, but when Covid-19 caused dine-in options to shut down, even more Americans flocked to them. “A brand like McDonald’s or Wendy’s, they generally have like 70 percent of business flow through the drive-through. And then it became 90, then it was 95,” Danny Klein, editorial director of QSR, a trade magazine covering the quick-service restaurant industry, told me. “You had this wave of consumers go to the drive-through and be introduced to it, and it’s just held as a bit of a habit that hasn’t gone away.” In 2022, drive-throughs accounted for about 75 percent of fast food restaurants’ revenue, Vox’s Whizy Kim reported last year.

For the drive-through haters, this highlights an uncomfortable truth: Drive-throughs are widespread and growing because tons of people use them. In a society that’s already built around driving everywhere, there’s some logic to this. They’re fast and convenient, and they can have a certain Americana charm. The National Restaurant Association reports that half of Americans use them at least once a week. I occasionally use a drive-through pharmacy because it’s so easy to do when I’m already en route to the grocery store; I’ve used drive-throughs to get tested for Covid multiple times (including one occasion, also in St. Louis, when I tried to walk up to a drive-through window and was refused service).

In the quick-service food sector, drive-throughs are now practically a requirement for staying competitive, and more businesses are adopting them. Chipotle started experimenting with drive-throughs, which it calls “Chipotlanes,” in 2018 and has been aggressively expanding them post-pandemic. The company is on track to open its 1,000th Chipotlane this year (out of its 3,400-some locations), according to an emailed statement attributed to chief brand officer Chris Brandt.

Chipotle just reported one of its best quarters ever, Klein told me, managing to increase its guest count, which is rare in the fast food industry. “Part of that is the accessibility that they’ve opened up across the country with these Chipotlanes,” Klein said.

Chipotlanes are digital-only, meaning that rather than ordering food on arrival, customers place orders online ahead of time and just arrive to pick them up, allowing the line to move much more quickly than at conventional drive-throughs (and, Brandt said, helping avoid traffic pile-ups). It’s like a take-out order, except you pick it up in your car. This drive-through system also makes business run more smoothly from Chioptle’s perspective; orders are filled on a separate assembly line where staff can “quickly and efficiently execute online orders without disrupting throughput on the front line,” Brandt said.

The rise of online order-ahead systems helps explain why drive-throughs have become even more popular in recent years: It’s made it even faster and more frictionless to pick up food. Some brands that have long offered traditional drive-throughs, like Chick-fil-A and Taco Bell, are adding dedicated lanes for mobile orders made in advance — part of what’s causing mega drive-throughification.

For chain restaurants, it’s easy to see why these developments look like progress: They make fast food consumption in car-dependent regions more efficient. But that efficiency is achieved at a heavy cost to people and communities.

The hidden costs of drive-throughs

One way of looking at the economics of a drive-through is that it derives its value from sucking value out of everything else.

Drive-throughs consign land that could otherwise be put to more productive use to be slabs of asphalt for car lanes. Many US municipalities have parking minimums, so building a drive-through on top of the legally mandated number of parking spots means “you have to essentially double the amount of space that’s dedicated to vehicles,” McMahan, the Minneapolis planning director, told me — and that’s just for drive-throughs with a single lane.

Because drive-throughs wrap around a restaurant, they usually only work with businesses housed in detached standalone buildings — rather than stores lined up together along a strip — wasting even more land. They depend on road infrastructure that’s expensive for cities to maintain, and they’re notorious for backing up onto streets, stalling traffic, and creating hazards for other road users.

“If you put a drive-through on a good street … you’re wrecking the walkability of that street, you’re wrecking the financial productivity of that street, you’re wrecking that street as a place,” Marohn said. And it’s no coincidence, he added, that drive-throughs are almost invariably linked with large fast food chains that siphon wealth out of local economies. “The types of businesses that do well in a drive-through environment are the types that mine capital from a community.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25322897/More_businesss_that_will_be_demo_ed_in_next_phase_of_development__1_.jpg)

Aubrey Byron for Vox

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25322887/U_City_in_Bloom.jpg)

Aubrey Byron for Vox

For small businesses without massive amounts of capital to invest, drive-throughs generally don’t make economic sense, Klein explained. “You’re competing with the Starbucks of the world if you’re trying to get that kind of lot [that can accommodate a drive-through]. Most smaller brands aren’t even willing to attempt that,” he said. The technology to make drive-throughs work is also costly, like speaker boxes and headsets. “If you’re someone like Chipotle, it’s just a different game of money. They’re really not worried about that upfront cost to the degree that a smaller brand would be.”

When I asked urban planner Joe Minicozzi what he thought about drive-throughs, he told me I was asking the wrong question. “What about them?” he said. “They suck.” And he’s right: Drive-throughs are not single-handedly responsible for the design choices that have made much of the US so dependent on cars, to the detriment of our safety, our quality of life, and the planet. If we got rid of all drive-throughs tomorrow, American communities would still be defined by sprawl, perilous roads, and massive parking lots.

The more fundamental problem, as Minicozzi sees it, is the system that allows and even encourages developers and big business to waste so much precious land on economically unproductive sprawl, ultimately forcing the public to pay for it in the form of road maintenance. “Why are we just trashing big chunks of our city as economic wastelands?” he said.

Still, if you’re looking for a totem of America’s “heinous land uses,” as the urban planning YouTuber Ray Delahanty put it, drive-throughs are not a bad choice. “They’re really significant design drivers,” McMahan said, requiring cities to build in a way that’s highly car-centric to accommodate drive-through traffic.

It adds up to an urban landscape that is, almost paradoxically, vast yet dominated by placelessness. Americans spend much of their days traversing non-places — settings for the movement and storage of cars rather than for humans to linger — making social connection “exhaustingly difficult,” as Muizz Akhtar put it in Vox, and contributing to our loneliness epidemic.

“A good part of any day in Los Angeles is spent driving, alone, through streets devoid of meaning to the driver,” Joan Didion wrote in 1989 of the consistently temperate region that somehow represents the apotheosis of car dependence and drive-throughs. “Such tranced hours are, for many people who live in Los Angeles, the dead center of being there.”

Cities are increasingly wary of drive-throughs

In 2019, Minneapolis became the most high-profile US city to ban construction of new drive-throughs, as part of its plan to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent by 2050. “We knew based on studies that had been done nationwide that there are higher rates of air pollution in places where vehicles are idling,” McMahan said. Residents had long complained about drive-through lines spilling out onto city roads, she added, and they were more broadly at odds with the city’s livability goals.

Before the city banned new drive-throughs (and parking minimums, which were eliminated two years later), McMahan said, “probably 50 percent of the time that we spent on a site was spent figuring out how vehicles were going to get in, be stored, and get out. And now we spend zero percent of our time thinking about that. … That means that time gets to be allocated to things like good-quality design and creating a better urban fabric.”

Atlanta recently prohibited new drive-throughs near its BeltLine, a system of walking and cycling trails, as a pedestrian safety measure. Some smaller cities and suburban communities, like Orchard Park, New York, have also banned them; in San Luis Obispo, California, they’ve been illegal for more than 40 years. Other cities are weighing drive-through bans and partial bans — a question that may become more urgent as drive-throughs expand their reach. Last year, the National Restaurant Association reported on local drive-through bans as a “developing issue.”

But big city restrictions may not end up mattering much, Klein told me, because the fast food industry sees its future in regions that are friendlier to the drive-through style of development. “They all want to go to the suburbs now,” he said. “That’s where I think you’ll see the very, very vast majority of their growth going forward.”

That’s consistent with what Brandt of Chipotle told me about the company’s expansion plans. “Small towns have been a major focus of our growth strategy over the last few years,” he wrote. “Chipotlanes allow us to enter these markets with a familiar and convenient access point for suburban families.”

This leaves suburban communities that are in the fast food industry’s crosshairs, like University City, with hard choices to make about what they want their future to look like. The city’s 2013 Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan had set a goal of making “University City the St. Louis region’s premier walk-able and bike-able city by creating a community with universal accessibility and transportation alternatives that enable residents, no matter their age or ability, to walk and bike to their destinations.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25322906/Market_at_Olive.jpg)

Aubrey Byron for Vox

This is hard to reconcile with a development pattern that’s tearing down local businesses to build fast food drive-throughs. Individual businesses will always come and go — and that in itself isn’t a problem — but city leaders have a duty to think deeply about what kinds of places they want to foster.

Reached for comment, Bwayne Smotherson, a University City council member who represents the ward where the new development opened, pointed to the economic benefits he believes it will have for the community (the city committed $70 million in tax increment financing to subsidize the project). He added that he wasn’t familiar with the environmental concerns with drive-throughs but that he considers the development accessible to pedestrians and cyclists.

“The wall is simply a design and function feature and not at all a barrier,” Smotherson wrote in an email, referring to the retaining walls in front of Chick-fil-A and Costco. It’s technically true that pedestrians can access the businesses if they’re very determined — but that really stretches the definition of walkable.

Drive-throughs are wildly popular in the US, Marohn said, because Americans are already traveling through environments where it feels unnatural and unpleasant to be outside a car; the drive-through just represents the logical culmination of building places for cars rather than for humans. The University City local businesses had already been hemmed in by such non-places that didn’t help them realize their potential, making them vulnerable to replacement.

A genuine alternative, Marohn said, would go a lot deeper than ditching drive-throughs. It would mean creating places where no one would think to miss them — places where people actually want to be.