What Larry Krasner has learned about trying to reform policing from the inside

I lived in Philadelphia for a long time, attending college at the University of Pennsylvania before returning years later. The city sits in a county where, politically speaking, the blue is drowning the red. Democrats outnumber Republican voters by three to one.

Still, it was noteworthy when Larry Krasner — perhaps the most famous of all the “progressive prosecutors” elected in recent years — all but ensured his re-election when he won the Democratic primary this past May. Krasner was first elected to the office of district attorney in 2017, and this most recent victory sent a strong signal that Philadelphia voters want his reformist work to continue.

It’s notable that voters overwhelmingly — by more than 30 percentage points — rejected the “tough-on-crime” narrative of his opponent, Carlos Vega. But how long will that hold?

Krasner sued the Philadelphia Police Department 75 times over more than three decades as a civil rights attorney. He’s been outspoken in his assertions that law enforcement is “systemically racist.”

Now, as district attorney, he’s trying to change that system from within. He’s drawn attention, most recently in a PBS documentary, for populating his team with criminologists and data scientists, for his efforts to end cash bail and reform the probation system, and his office’s attempts to reduce rates of incarceration, particularly among juveniles.

But when the goal is remaking something like Philadelphia’s entire legal system, how much can one person do?

You can hear our entire conversation (and there’s much more to it) in this week’s episode of Vox Conversations. A partial transcript, edited for length and clarity, follows. (Some of what you read below may not appear in the published podcast episode.)

Subscribe to Vox Conversations on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

What a DA can do, and what they can’t

My question may seem a little bit basic at the start here, but I think it’s kinda necessary for us to clarify this before we start delving into other topics: What does a district attorney do, specifically?

Larry Krasner

So a district attorney is a chief local prosecutor. District attorney signifies you’re not federal, you are at the state or county level. And you’re making decisions about whom to charge, what you should charge them with, and what you’re gonna do with that case.

It’s a position with a lot of power. And it’s a position that involves a lot of individual lives, not just defendants, but also people who’ve been victimized by crime and members of their family, neighbors, friends.

The decisions that a prosecutor makes have a profound effect on mass incarceration and how we spend our money. So in a sense, the chief prosecutor is there in court not only representing people who have a direct interest in the case but people who will never even hear of that case.

Jamil Smith

So knowing all that, in some respects, there’s just this culture of fear that some people — it could be police unions or political interests — have a vested interest in promoting. There was rising gun violence in Philadelphia last year, along with a lot of other cities, and there are people who are invested in blaming it on progressives wherever they sit, whether it be the DA’s office or city hall or what have you.

Larry Krasner

It’s the gift from Richard Nixon that just keeps on giving. This steady politics of fear, which in many ways is just code for historic and fundamental racism.

Last year, for example, we did have a historically terrible year in terms of gun violence, but crime across the country during the pandemic went down slightly. What we actually saw last year was not some form of lawlessness. What we saw was this massive surge in gun violence, a surge so massive that across the country in the 50 largest cities, the average increase was 42 percent. It was happening in cities with extremely hard-nosed Republican right-wing prosecutors’ offices, just like it was happening in cities where you had progressive prosecutors.

I consider myself to be a liberal, progressive person, but one thing the left doesn’t really talk about is that you know, in Philly, they were only solving 20 percent of shootings before the pandemic. They were only solving something like 40 to 50 percent of homicides.

And that is something that is felt just as dearly by people living on a particular block as the unjust incarceration of an individual. There are a lot of people in poor Black and brown neighborhoods who feel unsafe, unsafe from gun crime, but also unsafe from what police and prosecutors have been doing to them for decades. And they’re right. They’re right on both of them.

Jamil Smith

During your long career as a civil rights lawyer, more or less you’ve stood against the carceral state. But I understand that the number of people jailed in Philadelphia has increased by 30 percent just in the last year. What exactly is behind that?

Larry Krasner

So this is a city where, not so many years ago, there were 15,000 people in county custody. By the time I took office, there had been some good efforts to reduce it. When I took office in January 2018, we had 6,500. That number was down to about 4,800 before the pandemic hit.

The pandemic hits, and we and other criminal justice partners, including the public defender’s office, we make very concerted efforts to reduce the jail population even further, so it won’t become a super-spreader. And we got those levels down to 3,800, the lowest level of incarceration in Philly since 1985.

But we were up against a pretty big challenge, which is that the courts closed. We do not determine who is in jail or who is not in jail. So even though we got down to this unprecedented low, I shouldn’t say unprecedented, but lowest since ‘85, we started to see it climbing back up.

Jamil Smith

Let me rephrase that earlier question: What can’t a district attorney do?

Larry Krasner

It’s a lot of power, but it’s also limited in other ways.

For example, I would love to get rid of cash bail. I think it’s an awful system. I think if you’re so dangerous that you should not be on the street while you’re awaiting trial, then you should be held. But I also think if the matter is not serious, you don’t pose a serious danger to the community. Then I don’t really care if it’s your fifth retail theft for food; you should be out.

And what we have happening under cash bail is that poor people cannot pay a low bail and get out, so they sit in jail with all the negative consequences that come from that. We’ve tried to do as much as we can within the law, but I can’t change the law.

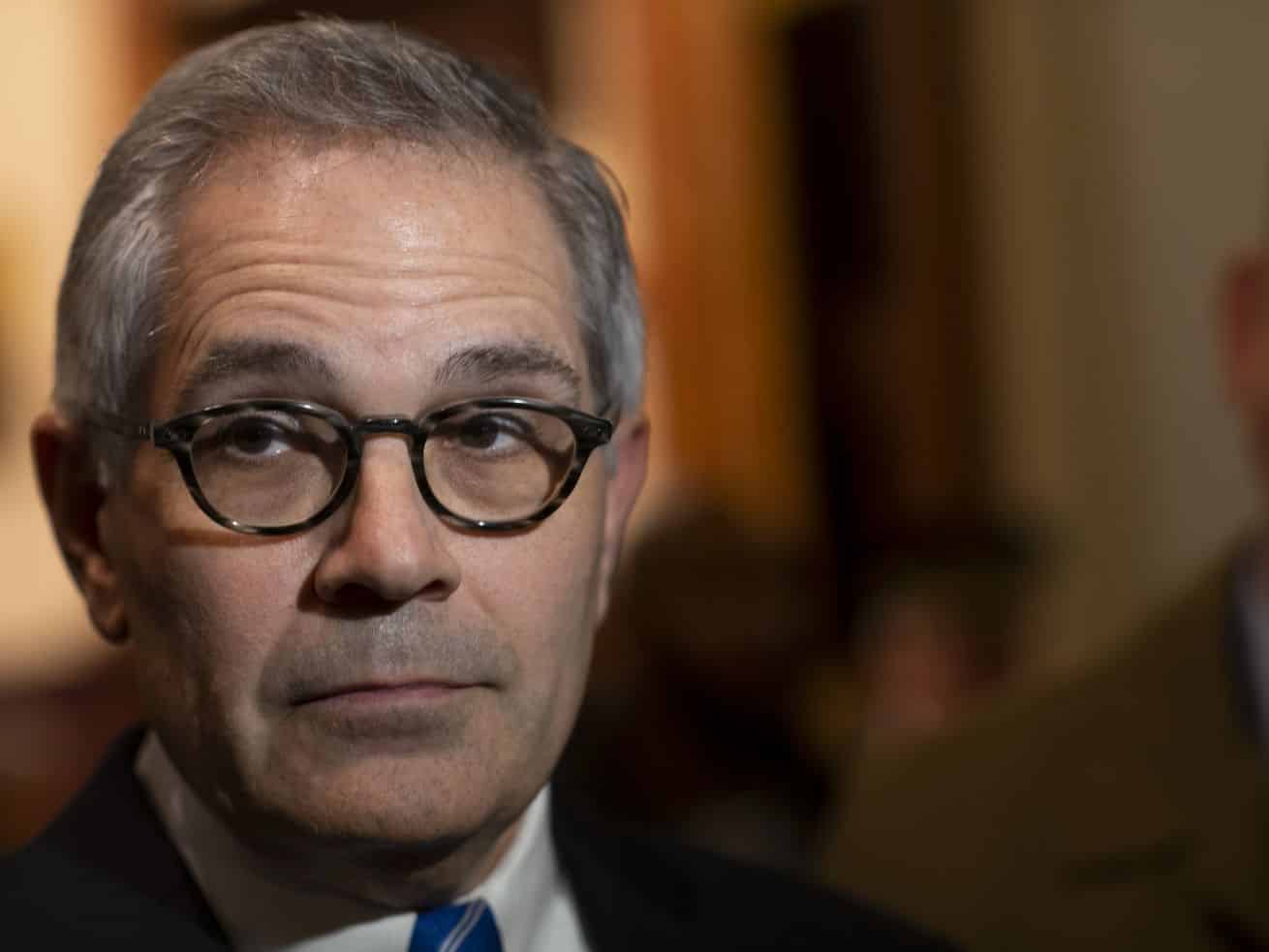

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22749887/1191069266.jpg) Photo by Mark Makela/Getty Images

Photo by Mark Makela/Getty ImagesSolutions-oriented thinking

Jamil Smith

You had said around the time the pandemic began spreading in this country, that you would try to simulate a no-cash bail system. Can you describe what you were trying to do and how effective you think it’s been?

Larry Krasner

Sure. Early in our administration was kind of a “phase one”; we found a lot of low-level offenses where we would never seek money. That was constructive and positive; it resulted in fewer poor people being stuck in jail for minor offenses.

Pandemic hits, and now we have this double crisis: We’re not just talking about public safety; we’re also now talking about a fatal disease that can affect people in custody, can affect everyone who comes in and out of that carceral facility. So you’re talking about prison psychologists, social workers, correctional officers, and every elderly relative they have at home.

Under those circumstances, we decided that the most we could do under Pennsylvania law was to ask on the one hand for no cash at all and on the other hand for a large amount of cash. That large amount was $1 less than a million for a specialized reason, which is that within the county correctional facilities, there was a rule: If bail was a million dollars, you had to be held in this very secure way that made it hard for the commissioner of our correctional facilities to socially distance people. The number was the best simulation of hold without bail that we could get, which would not also tie the hands of the person in charge of the jails.

It both succeeded tremendously and failed tremendously. A lot of the bail commissioners and a lot of the judges during the pandemic were very sympathetic to the idea that in order to protect everyone, we needed to let those people out of jail. So that worked very well.

At the upper end, where we were seeing someone who we believe had probable cause to have shot someone else, we’re going in. We’re asking for a dollar less than a million dollars bail to make sure they’re held, and we have judges who were used to giving $100,000 bail, $150,000 bail, $200,000 bail, and they didn’t wanna hear it. They really did not want to hear from us, that it should be higher than that. It has been a source of a lot of frustration both inside and outside the office.

Jamil Smith

Gun violence has been one of the main topics of conversation of anyone talking jurisprudence throughout the country. In the last two years that you’ve been district attorney, you’ve gotten to see from the inside how the system operates. What do you feel like are the best solutions, and what’s standing in the way of those solutions?

Larry Krasner

We have a really interesting crew here that never existed in this DA’s office before, headed by a criminologist and some data people, and when they geo map, this is what you see: The map of poverty is the map of unemployment, is the map of educational low achievement, is the map of mass incarceration, is the map of violent crime. It’s all the same map.

And Philadelphia is the poorest of the 10 largest cities. So I think, maybe more than some other cities, we very directly see the connection between poverty and everything that goes with it, and the persistence of violent crime.

There is no question that in medicine the biggest solutions are preventative. They avoid the harm in the first place. And the secondary solutions are, you know, the surgery. It’s the prosecution after the arrests because the blood is already on the ground and someone has been killed. There’s no question that prevention is where the biggest investment should be, and that’s not where we’ve been, as a country or as a city.

Jamil Smith

Your primary victory offers us the chance to look forward to the next four years. Criticism has been levied about the fact that it’s more disproportionately Black and brown people who are incarcerated than before. I just wanted to know what you feel about those particular criticisms and, knowing the powers of the district attorney’s office, what your capability is to address those concerns.

Larry Krasner

Some of what we’re seeing now is unique to a pandemic. We never had a situation, during my career, where the Philly courts were closed more than four or five days because of snow. We have had the Philly courts essentially closed for 15 months, so I don’t think we should read too much into the moment. But how can we improve things?

Once we get the courts running again, we can get back to a lot of policies that were making good headway. We can get back to policies of not prosecuting people for sex work. Not prosecuting people for possession of marijuana. At many different levels, we can advocate for the kinds of legislation that we need to do things like get rid of cash bail. We can advocate for sensible legislation around elimination of the death penalty in Pennsylvania. We can work on the vast enhancement of diversion because the consequences of conviction are so stark in terms of disabling someone from participating in the economy.

So we have plenty to do, and we have people in the office who are very energetic and excited; that’s part of it. We’re not the movement. We don’t lead the movement, but we are technicians for it.

One of the biggest challenges we face is that people believe it’s impossible. You know, the system has convinced them that it’s impossible. You have to be truly extraordinary. You have to be exceptional. No, you don’t. You really don’t, you know. While we are well-intended, we are not perfect people; we are not even really extraordinary people. You can be an ordinary person. You can get inside of a monster like this, and you can make some real improvements with it. And you can also fail and get up the next day and keep trying.

The future is now

Jamil Smith

What’s the impediment for you to sell people on working within the system to change the system, to sell especially Black Philadelphians, who continue to experience a disproportionate amount of the violence that the police department perpetuates?

Larry Krasner

Philly is the city that bombed itself, as you know. How do you tell people who have been subjected to that, that they should trust police or trust prosecutors? One way is that when you find innocent people sitting in jail, you get them out. And there have been some moderate, positive steps forward in Philadelphia.

We started a conviction integrity unit that at this point has released 20 people from jail on a total of 21 cases. One of them had two cases that should not have been convicted the way they were convicted. And the vast majority of them are clearly and absolutely and without question innocent of the crimes with which they were charged in the first place.

If we look at the phenomenon of a grassroots movement for criminal justice reform electing progressive prosecutors, what we see is that right now 10 percent of the United States has done exactly that, and often in the biggest jurisdictions, the jurisdictions that control mass incarceration to some extent.

Certainly, the thinking around this has been going on much longer, but all of those electoral victories are telling us something, and people who wanna run for mayor or who are mayors better pay attention, because it’s real and it’s coming. I think what these victories establish all over the country is that change is possible; it’s okay to do things that feel like an experiment.

Jamil Smith

I think of people wearing the progressive label without actually putting that into their policies. I think about Ellen Rosenblum up in Oregon, who after the Supreme Court verdict on nonunanimous jury verdicts has the power to do something about that. The fact that they’re not applying that retroactively to people who’ve already been sentenced astounds me.

What do you think about that particular Supreme Court case and sort of living up to that label?

Larry Krasner

We have to acknowledge and accept that there is a variety of thought within a group of people who are trying to be modern, who are trying to be de-carceral. We may not all agree on certain things, and that’s okay. But it’s not okay to be a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

I think that one of the ways that we can really move forward is to recognize that often the law, when it comes to justice in the United States, is a floor — but it’s not the ceiling. And even where the law provides these sort of minimal protections, often prosecutors have the discretion to require more.

And we can make decisions on things that are categorical. Like there are certain things I’m just not gonna charge; there are mandatories I’m just not gonna pursue because I think judges should actually have the discretion to do what we elected them to do, to make decisions about individuals and individual cases.

People don’t walk into a courtroom after they’ve been involved in a fistfight — they don’t walk into that courtroom with a number on their forehead. There is no obvious proper number of months or years of jail or supervision for a fight that results in a broken jaw. It’s a serious offense that affected someone’s life seriously and should be taken in that context. But we need to be careful. It may be that a lot of 10-year sentences should be three, that a lot of two-year sentences could be probation.

Jamil Smith

I mean, we’re talking about setting some guidelines here, and this is something that we, as Americans, just kind of accept. Recklessly, what is the power of a district attorney to fix that? Beyond making sure that you don’t prosecute certain crimes?

Larry Krasner

Let me just digress for one second to tell you how stupid a lot of these sentencing guidelines are. The history of sentencing guidelines in Pennsylvania was that people thought consistency was nice. Some very rural counties were giving out different sentences than some very urban counties. You might only have one homicide in a decade in a particular county as opposed to a much larger number of homicides either in Pittsburgh or in Philadelphia.

So they did not come up with a system of sentencing guidelines that were based upon criminological data or recidivism statistics or anything else that might shed light. What they did is they averaged it, and guess what? This drives up the sentences you’re supposed to give in the big city, and it drives down the sentences you’re supposed to give in the smaller locations. The populations are in the big cities. The large number of cases are in the big cities. Very harmful stuff, very wasteful.

So what can I do? Well, No. 1, in many instances, I don’t have to pursue a mandatory, so I don’t. In some instances, we have to make a charging decision about whether we’re gonna pursue a particular charge that has a drastic effect on the sentencing guidelines, and if we think it’s unjust and unfair to pursue that charge because it calls for some kind of ridiculously high, inappropriate sentence, then we can choose not to bring the higher charge.

We are strong believers in individual justice, and that means giving judges discretion and trying to get all the information you can, and trying to be as fair as you possibly can. I think that there are obviously some inconsistencies when you give more discretion to judges to make their own decisions. But I would rather have some inconsistency than a system that is predictably and consistently unjust, which is what we have with these three-strikes laws, mandatory sentencing laws, and a lot of the sentencing guidelines, provisions that are completely unscientific.

Jamil Smith

You’ve been characterized often as a radical. I saw that a lot in the articles that were concern-trolling about your potential doom in this primary. What do you think of that label, particularly within the context of what you’re trying to accomplish?

Larry Krasner

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with being a radical. But do I think it’s accurate? No. You know, this terrible radical voted for Joe Biden. Woohoo.

The radical experiment, in my mind, was mass incarceration. The venomous approach of Richard Nixon, the war on drugs, everything that came after. This essentially cloaked effort to go after anti-war protestors and to go after Black people. When you go from X number of people in jail to five-X people in jail within a few decades, what’s so radical about trying to go back to where we were in the first place?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22749921/1218352303.jpg) Photo by Cory Clark/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Photo by Cory Clark/NurPhoto via Getty ImagesAuthor: Jamil Smith

Read More