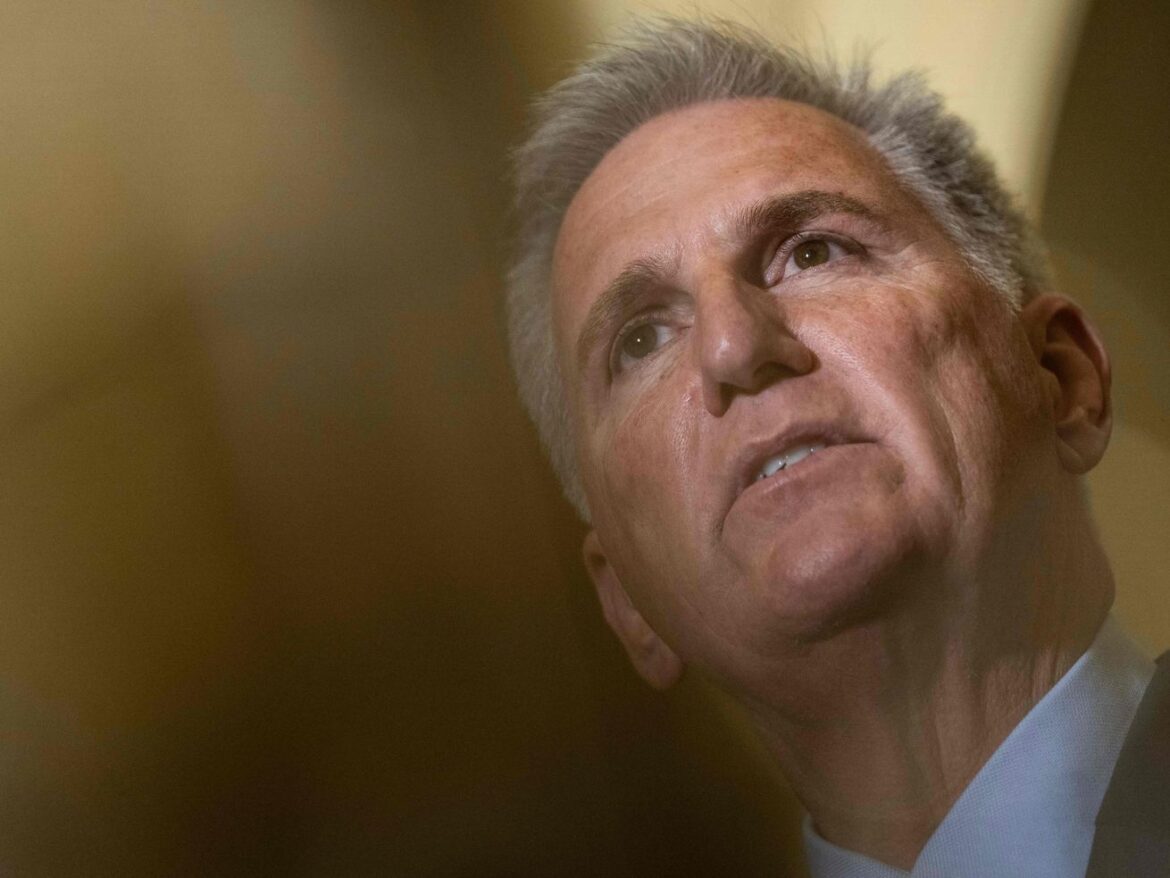

House Speaker Kevin McCarthy backed an inquiry despite no evidence of Biden’s wrongdoing.

House Speaker Kevin McCarthy has announced an impeachment inquiry into President Joe Biden, a move that comes despite no evidence of Biden’s wrongdoing at this time.

“House Republicans have uncovered serious and credible allegations into President Biden’s conduct,” McCarthy claimed on Tuesday. “These allegations paint a picture of a culture of corruption.”

McCarthy went on to suggest that Republicans have evidence Biden used his position as President Barack Obama’s vice president to help enrich his family, particularly his son, Hunter Biden, and that he lied about it in an attempt to cover that up.

Despite McCarthy’s assertions — and months of GOP investigations into Biden and his family’s business dealings — Republicans have not been able to find proof that Biden actually engaged in any illegal behavior, or that he used his office to profit himself.

As such, the inquiry appears driven more by the House GOP’s internal dynamics and political goals than the substance of the allegations. Earlier this year, McCarthy gave any member of his caucus the ability to call for a vote on his ouster in exchange for the speaker’s gavel. In recent weeks, some on his party’s right flank have threatened to oust him if he didn’t pursue an impeachment inquiry, putting pressure on him to take that step.

That’s not to say all Republicans are behind the move, a reflection of just how wide an ideological spectrum McCarthy needs to keep happy. Although more conservative Republicans like Reps. Matt Gaetz (R-FL) and Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA), have been urging an impeachment push for months, others including Rep. Don Bacon (R-NE) have previously spoken out against it.

Even the way McCarthy decided to launch the inquiry — unilaterally instead of by a full vote, as he’d said ought to be the only way impeachment inquiries are authorized — is reflective of how big a tent the speaker needs to cater to. McCarthy’s majority depends on lawmakers who won in districts Biden carried; forcing them to vote yes on an inquiry would have been damaging to their reelection prospects next year, and could have put the GOP majority in jeopardy.

Republicans also hope to see their nominee, likely to be former President Donald Trump, retake the White House next year. But Trump is beset by many legal problems. The inquiry, and a possible impeachment, will allow the GOP to go on the offensive against Biden ahead of the presidential election in 2024 and defuse some of the attention on Trump’s legal baggage.

The inquiry will be led by three House committees, and comes as Congress faces a tight timeline to pass legislation ahead of the end of the year. Some Republicans, particularly those in the Senate, have suggested the inquiry will become a distraction from finding consensus on government spending bills prior to a deadline at the end of September.

“We’ve got our hands full here trying to get through the appropriations process,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell told Punchbowl News, adding, “I don’t think Speaker McCarthy needs any advice from the Senate on how to run the House.”

Why some Republicans want an impeachment inquiry — and others don’t

Now that an impeachment inquiry has formally been launched, three House committees — Oversight, Judiciary, and Ways and Means — will continue their investigations into Hunter Biden’s business dealings as well as President Biden’s involvement.

So far, Republicans have found that Biden’s son, Hunter, made millions of dollars while his father was vice president. Devon Archer, a business associate of Hunter Biden’s, has previously testified to the House Oversight Committee that businesses were interested in working with Hunter in part due to his proximity to the Biden “brand.”

One key piece of evidence Republicans have cited from Archer’s testimony is that Biden participated in roughly 20 phone calls with Hunter’s business contacts. However, Archer stressed those encounters consisted of small talk like the weather and not issues of substance. Archer also testified that he hadn’t seen President Biden attempt to use his office to help Hunter advance his career.

Some “evidence,” such as claims Biden engaged in quid pro quo schemes, have been disproved. Others, like testimony from whistleblowers who claim the government gave Hunter Biden lenient treatment in its investigations into potential misconduct, have been largely discredited. As the New York Times explained, “there is no evidence that Mr. Biden ordered that his son get special treatment in any investigation.”

Overall, House Republicans’ investigations have not found any actual, concrete proof of wrongdoing by President Biden. As a result, their decision to open an inquiry is surprising, since it’s historically not been done until there’s significant evidence of misconduct. Republicans have argued that the inquiry is to help them gather this information: It provides a legal framework that could enable these committees to gain more subpoena powers for documents, though the legal precedent for this is unclear, and any subpoenas are likely to be met with lawsuits.

Currently, the House does not yet have a strong case that Biden committed “high crimes and misdemeanors,” one of the charges a president can be impeached for. Multiple Republicans — including Senate leaders like John Thune (R-SD) and Mitt Romney (R-UT) as well as House members like Rep. Dave Joyce (R-OH) — have expressed concerns that the GOP is moving forward on an inquiry without providing clear evidence of the offenses it will center on.

“You need to explain to the American people why it is you think an inquiry of that nature is called for and to suggest a possible wrongdoing that would justify investigation. That hasn’t happened yet,” Romney said, though he’s also said he’s open to the inquiry. “[I’m] not seeing facts or evidence at this point,” Joyce told Forbes earlier this week.

Two legal impeachment experts who spoke with Time have described this effort as potentially the weakest that’s ever been launched in US history. “I honestly don’t know that there is any evidence tying the president to corrupt activities when he was vice president or now,” Philip Bobbitt, a Columbia law school professor, told Time.

What could happen next in the impeachment inquiry

Since this is in the inquiry stage, it’s possible this doesn’t move to an impeachment vote. For a president to be impeached by the House, the majority of the chamber has to vote for articles of impeachment — or charges — against them. That’s a tough sell given the political backlash moderate Republicans in districts that Biden previously won would face. In 2022, 18 Republicans won districts that Biden also won in 2020. While it’s possible they could be swayed, and many have signaled support for the inquiry, they’d likely face a serious penalty from voters if they made such a move and put Republicans’ already slim margins at risk.

After a successful impeachment vote, the Senate typically holds a trial during which lawmakers present a case and the president puts forth a defense. The Senate ultimately votes on convicting the president, with a two-thirds majority needed in order to remove anyone from office. Democrats could potentially change or ignore Senate rules to avoid holding a trial, though as McConnell previously explained during the Trump administration, doing that is dependent on lawmaker support.

Still, even if Biden were to be acquitted in the Senate, he would, like Trump before him, be an impeached president. And that would provide Republicans something to rally around — and hang over Biden’s head — as election season goes into full swing.

Republicans hope to hurt Biden in an election year

The Biden impeachment push is a continuation of Republican attempts to put heat on the White House. Already, the House has focused heavily on investigations that allege bias by the DOJ and FBI, and that scrutinize the administration’s policies on everything from Afghanistan to immigration. As Vox’s Christian Paz reported, these investigations have yielded few breakthroughs, however, and haven’t generated strong public support.

An impeachment inquiry would add to existing investigations that House Republicans have already done on the Biden family’s business practices — and be a way for Republicans to try to get more of the public onboard.

Even though it has no substantive foundation, for example, an impeachment inquiry could be used to try to dent perceptions of Biden. As political scientists Douglas Kriner and Eric Schickler have found in the past, negative investigations can hurt presidents’ approval ratings over time. And as was the case in Republicans’ Benghazi investigations of former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, such reviews can sometimes stumble upon findings that can be politically weaponized.

Despite concluding that there was no new evidence of wrongdoing by Clinton, that panel scrutinized how Clinton had used a private email server while secretary of state, a finding that spurred another investigation by the FBI, which became a central issue Republicans successfully used against her in the 2016 election.

Impeachment could also be a way for Republicans on the campaign trail to suggest that Biden and Trump are both facing legal scrutiny even though the two cases are not comparable at all. By initiating an inquiry, Republicans can attempt to muddy the waters when it comes to how Biden is perceived, arguing that the two candidates both come with ethical baggage.