Maybe the world doesn’t need to know every thought you’ve ever had.

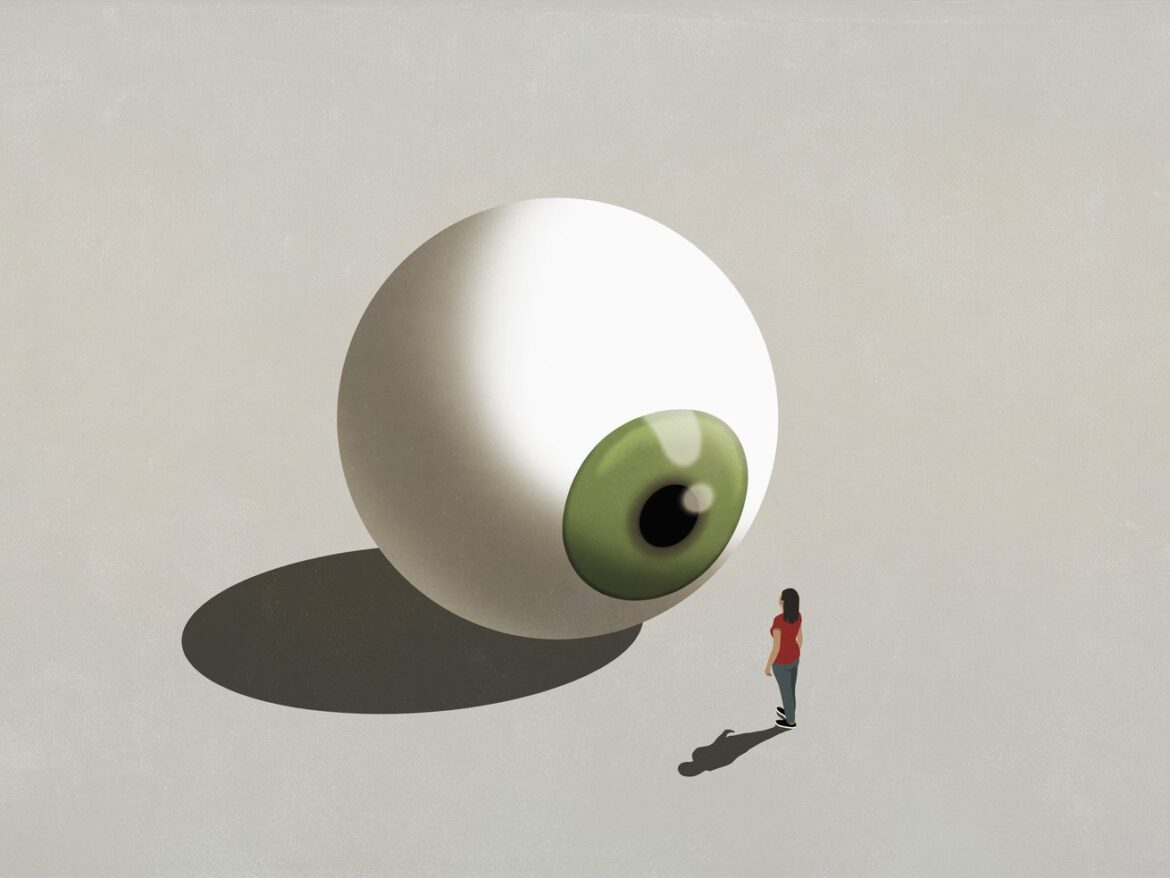

“The basic experience connected to shame,” wrote English philosopher Bernard Williams, “is that of being seen, inappropriately, by the wrong people, in the wrong condition.” Scrolling on my phone, I find myself thinking it is a good thing that Williams died in 2003 because an hour on any social media platform might have otherwise killed him. To be seen inappropriately (say, simulating sexual intercourse) by the wrong people (for example, the other tourists around you and also the entire internet) in the wrong condition (on a bridge in Venice), has become the goal for increasing numbers of people.

Somewhere over the course of the past 10 years, we decided everything should be normalized; that to be cringe was to be free; that you should not only wholly accept but also share every thought or experience you ever have, no matter how embarrassing or repulsive. Why not take to Twitter to loudly and proudly announce that you have never made a woman orgasm or that you don’t wash your ass in the shower, with absolutely no prompting? The dominant culture of the internet has endeavored to convince us that all our emotions are valid, with increasing numbers of people further affirmed in their wrongness by therapy-speak they apply selectively to make themselves look and feel better. Shame, for its part, has come to be regarded as an inherently toxic, destructive emotion: a stand-in for self-loathing and unaddressed childhood trauma.

To be clear, it’s good that some things have been normalized: not wearing a bra, homosexuality, oat milk. But the flipside of living in a world where you are repeatedly told you shouldn’t be ashamed of anything is one in which a literal British prince — heretofore the most stiff-upper-lipped, shame-filled demographic in all of history — has been convinced that he needed to publish a memoir detailing, among many other things that I have learned against my will, the circumstances in which he lost his virginity in toe-curling detail. When did it become so undesirable to have secrets?

Shamelessness and attention-seeking behavior are two sides of the same coin, and as fame in and of itself has become the endgame for an increasing number of people, we have turned shame into a dirty word, accusing those that have it of being scared to be their “true” selves. The currency of our time is attention, and a need for public affirmation and a sense of shame do not generally go hand in hand.

Having no shame has become synonymous with fearlessness, a way of signaling that you are true to your desires and don’t care about what others think of you or your actions. But … what if you did? What if I told you that a sense of shame can be good, actually; that it can signal self-respect and dignity rather than self-loathing. Shame can help you remember that regardless of what that Spotify playlist wants you to believe, you’re not the main character of the world — you’re one in 8 billion and you should at least try to live in a way that honors others too. In a world with a stronger sense of shame, wearing a small piece of fabric on your face in order to possibly save the lives of others would never have become a contentious issue.

“We have to be careful with distinguishing between healthy and unhealthy forms of shame,” says Taya Cohen, an associate professor of organizational behavior and business ethics at Carnegie Mellon University, when I present her with my theory. “A lot of the work that has painted shame in a negative light has conflated feeling bad about ourselves and [social] withdrawal, but in some cultures, those aren’t as closely linked. You could feel bad about yourself or anticipate that you would, but that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re going to hide. That’s more of an individualistic [culture] thing.

“The problem with shame is it can be motivating because people want to avoid it, but once a person feels it, it can be problematic if they don’t think they can change,” she adds. “The prevailing thought is that shame is feeling bad about yourself as a whole person, whereas guilt is focused more narrowly on feeling bad about a more specific behavior.”

In cultural anthropology, different cultures have traditionally been categorized based on whether they are primarily ruled by guilt or shame, terminology popularized by Ruth Benedict in her 1946 book The Chrysanthemum and the Sword, in which she describes America as a “guilt culture” and Japan as a “shame culture.” Guilt has come to be seen as the Western (and therefore rational) emotion, tied to law, punishment, and a moral code held up by one’s conscience. In Eastern “shame cultures,” where the emphasis is on concepts such as pride and honor, punishment is doled out in the form of social ostracization and a loss of face. And while it’s obviously unhealthy to live consumed by fear of what others think of you, it’s becoming increasingly clear that the hyper-individual, atomized culture in which we are told not to care what anyone thinks of us or our actions is not working out so well either.

The exaltation of guilt over shame has led us to a place where accountability never seems to go beyond a Notes app apology. White guilt, guilt around calorie consumption, guilt about our carbon footprint, middle-class guilt, fake Catholic guilt suffered by reactionary e-girls looking for meaning in their empty lives — it’s an emotion that is for all intents and purposes nothing more than a big “oops.” Simply confessing to feeling guilt seems to be enough to alleviate it.

An inherent sense of shame, on the other hand, prevents you from doing the things that can later cause you guilt or embarrassment: overstaying your welcome at someone’s house, boasting about not tipping your UberEats driver, volunteering to your 1.7 million followers that you willingly live with a mouse problem in a deranged stand against wealth.

In their paper “Emotion: A Multidimensional Approach to the Relationship Between Individualism-Collectivism and Guilt and Shame” (2019), Cohen and a team of five other researchers studied over 1,000 people from five countries (the United States, India, China, Iran, and Spain) and found that “individuals culturally socialized to be more interpersonally oriented (i.e., horizontal collectivism) are more motivated to engage in reparative action following transgressions, whereas those culturally socialized to be more attuned to power, status, and competition (i.e., vertical individualism) are more likely to withdraw from threatening interpersonal situations.”

In other words, in the United States where the culture is individualistic, it is possible to withdraw and hide from other people because you’re not so embedded in the collective. This is in contrast to more communal cultures where you have to face up to what you’ve done if you want to be included in the community, something that is in itself a higher priority.

A healthy sense of shame can act as a bridge between the personal and the collective in a culture that pushes us to valorize the ego over the other. Perhaps the proliferation of shamelessness is linked to the erosion of community — in a world where we are increasingly alienated from people around us who would traditionally have acted as arbiters of taste and acceptability, it is no wonder people are squeezing pineapples between their thighs and then drinking the juice for online attention. The social bonds of the collective have been replaced with the approval of an unseen audience.

“In the past, if you wanted to fit in within your local community, you had to act in a way most people thought was appropriate. On the internet, a person can behave in ways that the vast majority of people find completely unacceptable, but they’re getting positive feedback in the form of people sharing it,” says Cohen. “It does suggest that maybe we’re tacitly accepting it, and tacitly accepting the person who has done it — because they’re not feeling ashamed, they haven’t been ostracized. In fact, the opposite has happened.”

Thanks to the internet, more people have also gained access to a framework of words that used to be the preserve of the few who sought professional counseling or were freakishly into self-help books. Those few have become many, and while it’s great that therapy has been normalized, its language has taken on a life of its own and trickled down so far into the mainstream that during last year’s Love Island, outraged viewers started incorrectly calling out a female contestant for “gaslighting” (she was merely doing what she had to do). Its lexicon is increasingly used to justify antisocial behavior, with almost anything able to be excused under the umbrella of “self-care.”

The platforms themselves, the algorithms they employ and contemporary standards they create, favor those who are willing to push the boundaries of social taste and self-promotion, whether that is making a TikTok of yourself aggressively humping the side of a pool with your fellow content creators or reposting every mention of your latest piece of work to your Instagram story like a child who has received a gold star at school and wants their mum to stick it on the fridge. We are incentivized, in the eternal quest for attention, to share everything, no matter how boring or ill-advised.

In the interests of being nice, I will stop short of arguing for social ostracization, although I do personally think that most people who feature on this account should be locked inside one big house (call it a hype prison) and forbidden from interacting with the rest of us until they have thought about their actions and made earnest front-facing camera apologies. In a world increasingly defined by soaring levels of loneliness and disconnection, a healthy sense of shame can be a powerful moral force that rebinds the social and communal fabric through a belief in a common good and a desire to avoid harming others. It allows us to remember our humanity. Instead of doing everything we can to run from and bulldoze over feelings of shame, perhaps it’s time to learn to sit with our mistakes and the discomfort they can make us feel, instead of living in hope of unearned absolution.

Niloufar Haidari is a freelance culture writer from London who tries to spend as little time there as possible.