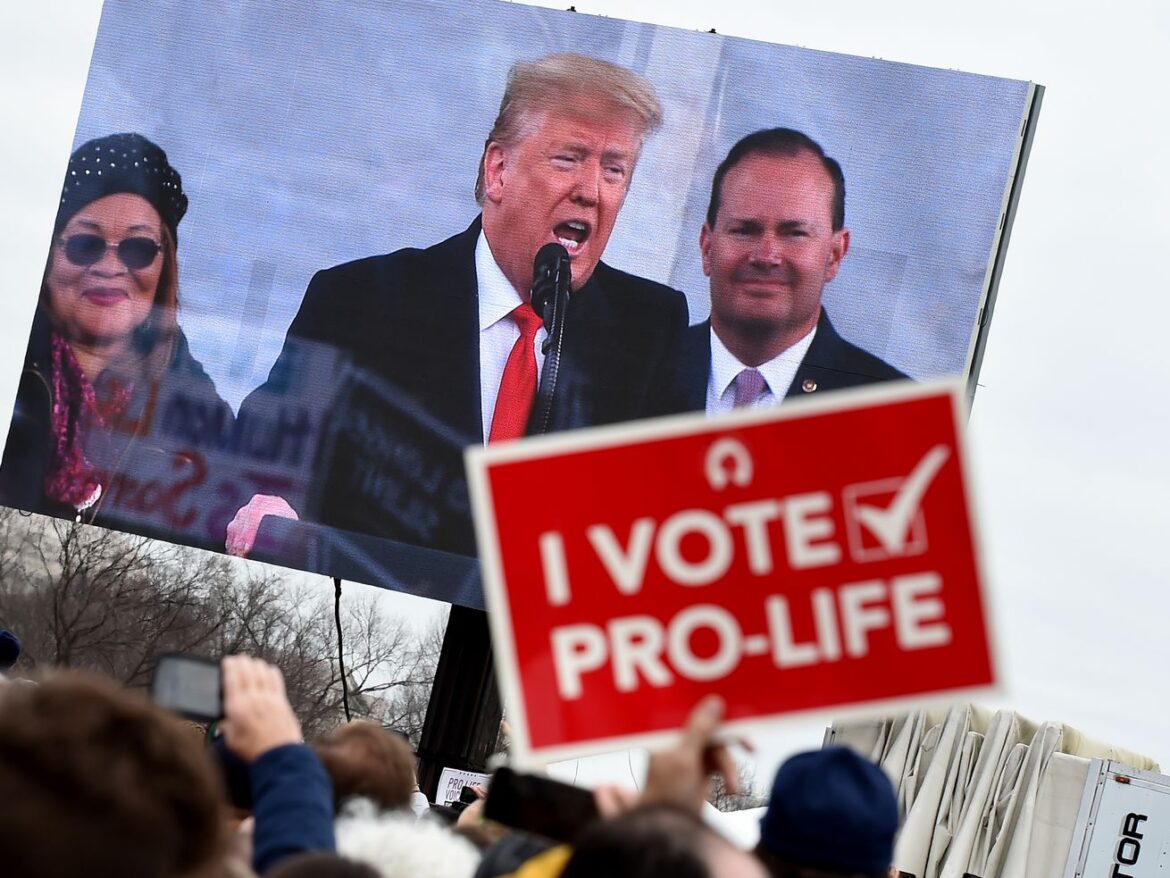

Trump and pro-lifers own the Republican Party. That’s bad for its political future.

In the past 48 hours, three major news events have revealed a fundamental problem for the Republican Party’s political future.

First, Donald Trump was formally indicted in New York — a move by prosecutors that appears to have unified the party around him, cementing his already rising poll numbers and making it harder to imagine the GOP ever moving on. This is despite the fact that 60 percent of Americans approve of the indictment, and he remains politically toxic among the majority of Americans.

Second, Republicans lost control of the Wisconsin Supreme Court in an off-year election — a campaign where abortion was “the dominating issue,” per University of Wisconsin political scientist Barry Burden. The repeal of Roe v. Wade brought back an 1849 state law, never technically repealed, that banned abortion at all stages of pregnancy (with an exception for the mother’s life). Janet Protasiewicz, the liberal candidate in the Supreme Court race, openly campaigned on her support for abortion rights. She won by a comfortable margin in a closely divided state — yet another sign that strict abortion bans are seriously unpopular.

Third, the Florida Senate on Monday approved a six-week ban on abortion — a bill pushed and supported by Gov. Ron DeSantis. The GOP’s most plausible non-Trump candidate has now tied himself to one of its most unpopular policy positions with a proven capacity to power Democratic electoral wins.

The developments capture the Republican Party’s problem in a nutshell. Maryville College historian Aaron Astor put it well:

The GOP has two big albatrosses for 2024: Donald Trump and laws that ban first trimester abortions. Both are popular with the GOP base and reviled by the majority of American voters. Abandon them and demoralize the GOP base. Embrace them and get crushed by a mediocre Dem. https://t.co/sO0gUOVsqB

— Aaron Astor (@AstorAaron) April 5, 2023

The party of Trump and six-week abortion bans is a party that’s starting the 2024 race at a huge disadvantage.

A failure of “plutocratic populism”

Taking unpopular positions that the base demands is nothing new for the GOP.

In their book Let Them Eat Tweets, political scientists Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson extensively document that the party’s modern economic agenda — centered on tax cuts for the wealthy — is exceptionally unpopular with the majority of Americans. However, the ultrarich donors that the party depends on demand these policies, which makes breaking with them difficult if not impossible.

The culture war, according to Hacker and Pierson, is the party’s principal strategy for solving the problem. If you focus elections on issues like race, crime, and immigration, you can rile up the base — and even appeal to a certain kind of moderate voter — without having to compromise on the 1 percent’s economic demands.

They call this strategy “plutocratic populism” — and Donald Trump, a rhetorically populist billionaire whose biggest legislative accomplishment was a hefty tax cut for the wealthy, perfectly illustrates how it works.

Yet for plutocratic populism to function as a political strategy, it has to be at least a little bit popular. The GOP needs to attack on cultural issues where it can win over enough support to command a sufficient electoral coalition, with politicians who can effectively carry the message to America. The problem, right now, is that it seems like they have neither.

After the Dobbs ruling last year, abortion rose to the top of the cultural agenda as Republicans across the country pushed strict bans. This was, in no small part, why Democrats managed a historically strong performance in the 2022 midterm elections: This time around, they were on the right side of popular opinion on a highly visible and highly salient cultural issue.

“Banning abortion without any exceptions is probably as unpopular, or more unpopular, as defunding the police,” David Shor, a leading Democratic data analyst, told me last year. After Dobbs, “abortion went from being a somewhat good issue for Democrats to becoming the single best issue.”

Wisconsin’s results just proved that Shor was right. Protasiewicz did well in urban and suburban areas with higher levels of college-educated voters, exactly the types who typically hold moderate and liberal views on cultural issues. She even overperformed in Waukesha County, a suburban county that’s a historic Republican bastion, indicating the changing tides on cultural issues.

In theory, the smart move for plutocratic populists would be to take the L. They should soften the party’s position on abortion, try to enact looser rules at the state level than the ones they’ve been pushing, and reorient the political conversation to more favorable territory.

Yet as Florida just showed us, that’s not what’s happening. At a time when it has become obvious that taking a hard line on abortion is political kryptonite in general elections, DeSantis — the party’s rising star — has expressed support for what my colleague Rachel Cohen called a “radically restrictive” bill that would “not only decimate what’s left of abortion access for residents in Florida but also significantly curtail care for women across the South.”

The reason why he’s taking such a position is not hard to understand: The Republican base really, really cares about abortion. Republican officials who want to win primaries — people like Ron DeSantis — need to campaign as aggressive anti-abortion champions.

But what’s good for a primary is bad for the general.

“The magnitude of this [Wisconsin] result … underline[s] how great a risk DeSantis is taking as a potential general election nominee by steaming toward a 6 week abortion ban,” writes Ron Brownstein, a senior editor at the Atlantic. “Once again a state outside the red core sends a clear signal it wants abortion legal.”

One can say the same thing about Trump himself, who is currently increasing his already-large margin over DeSantis in the GOP primary. It’s very clear, from years of opinion polling, that Trump is viewed negatively by a majority of Americans. Given how famous he is and how much he’s dominated the news since 2016, that opinion is very likely to be fixed and mostly unchangeable. There is no credible case that being indicted in New York, and potentially elsewhere, will make him look better to moderates and swing voters.

But it will likely improve his standing in the GOP primary.

Many Republican primary voters believe, very deeply, that society’s liberal elite is against them and Trump and that the indictment is yet another part of this vast plot. Rivals like DeSantis, recognizing this reality, are already lining up to attack the prosecution — putting them in the awkward position of saying that Trump is the great conservative victim, but that they, and not him, should be in charge of the political fight against his persecution.

This means that the GOP will most likely be in a position of nominating a radically unpopular candidate to advocate a radically unpopular agenda in the 2024 election.

Does this mean that they will certainly lose? No, of course not. American politics is tightly polarized, with narrow margins for both parties. A major event in the world — like, say, a painful recession — could still yield a Republican victory. But there’s no doubt that the politics of abortion and Trump is putting the party in a difficult bind.