Brazil, Argentina, South Africa, and Australia had heat waves in the past few months. Now spring begins.

It’s been a hot, brutal, record-breaking summer across much of the world, and it’s not quite ready to let go as late-season heat waves bake parts of the United States, the United Kingdom, North Africa, and the Middle East.

The long goodbye is a fitting cap to a season of deadly heat that contributed to severe drought in some areas and torrential rainfall in others. High temperatures also set the stage for wildfires in Greece and Turkey, Canada, Hawaii, and Louisiana.

But at least people north of the equator can look forward to some relief as autumn and winter set in. The 850 million people in the Southern Hemisphere, on the other hand, are emerging from some of their hottest winter temperatures on record and bracing for even more heat as the warmer seasons begin.

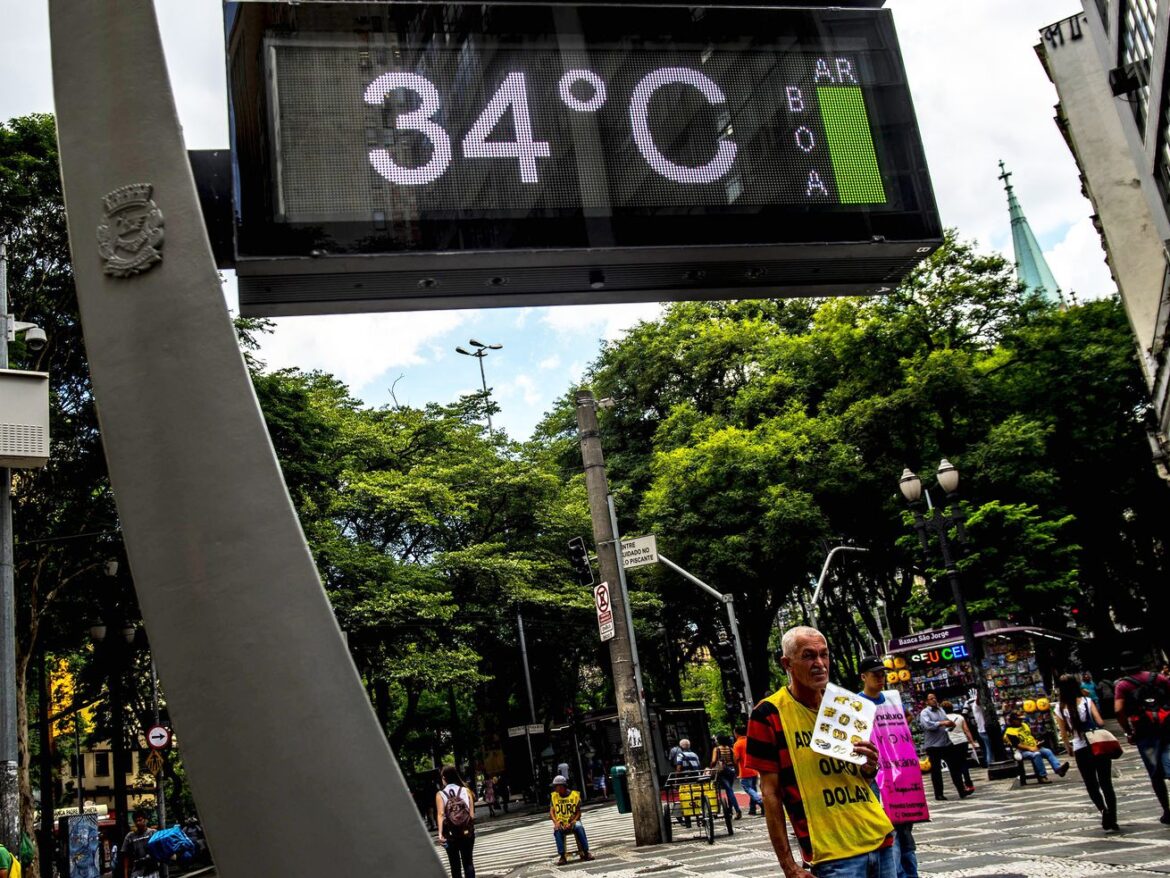

In fact, the weather was pretty much like summer in June, July, and August across parts of South America, Africa, and Australia. Peruvians went to the beach last month as temperatures reached 82 degrees Fahrenheit. Similarly balmy weather engulfed Paraguay and Chile. Buenos Aires, Argentina, reached 86°F, the hottest August temperature in at least 117 years. The heat was downright dangerous in Brazil as thermometers ticked above 100°F. Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology confirmed this month that Australia experienced its hottest winter since record keeping began more than a century ago. Even down near the South Pole, warmer air and water have led to the lowest sea ice extent on record around Antarctica.

“Some of these set new records by a large margin, also known as ‘record shattering’ extremes,” explained Michael Grose, a senior research scientist at CSIRO, Australia’s government science agency, in an email.

Record-breaking winter heat in the Southern Hemisphere.

Perth airport in Western Australia just recorded its hottest winter day on record (records go back 79 years here).

Cape Town Observatory, South Africa records its hottest August day on record with 32.9°C. Records… pic.twitter.com/O7kK1yZCLI

— Scott Duncan (@ScottDuncanWX) August 31, 2023

Winters tend to be milder in the Southern Hemisphere than in the North, and many of the factors that cranked up the heat across North America, Europe, and Asia in recent months are doing the same thing below the equator: Ocean temperature cycles like El Niño are in their warm phases, while greenhouse gasses from burning fossil fuels are accumulating in the atmosphere, warming the planet and changing its climate. So the hot winter across the Southern Hemisphere this year lined up with what scientists expected.

“The seasonal forecast told us that we will have a warm winter time, so we were not surprised,” said Matilde Rusticucci, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Buenos Aires and a researcher at CONICET, Argentina’s national science research council. But “it wasn’t normal.”

Now that spring is in the air, researchers expect that Australia, Africa, and South America will experience even more extreme weather — not just high temperatures, but more intense rainfall. As the Northern Hemisphere cools off, this year of record-breaking weather is only heating up in the south.

The Southern Hemisphere’s unusually warm winter, explained

First, a quick trip back to elementary school: Earth has seasons because the axis it spins on as it revolves around the sun every 365 days is tilted, rather than completely vertical. That tilt means that for about half of the year, the Northern Hemisphere is pointed more toward the sun than the Southern Hemisphere, leading to longer days and more accumulated heat, thus creating summer. The process then reverses in the Northern Hemisphere’s winter, which is also summer in the south.

But there are other factors at play when it comes to how the seasons manifest across the planet, namely the distribution of land and water.

“The biggest difference between the Northern and Southern hemispheres as a whole is that the North contains more large continents with an Arctic Ocean, whereas the Southern features fewer large land areas, the Southern Ocean and then Antarctica,” Grose said.

The oceans act like shock absorbers for weather and have a moderating effect on the climate. The Southern Hemisphere, with proportionately more ocean than land, tends to have a less drastic swing between seasons than places above the equator. That also means that winters in the south start from a warmer baseline than winters in the north.

So countries like Brazil rarely get chilly weather in the winter. “It’s dry and mild,” said Fábio Luiz Teixeira Gonçalves, a professor of geosciences at the University of São Paulo. Temperatures typically range between 53°F and 78°F, but they have been about 3.6°F higher on average since May around São Paulo. Those higher average temperatures fueled more extreme heat.

Extraordinary heat in South America is rewriting climatic books:

Last 2 days #Paraguay had stations with Tmin >30C

Yesterday the min. temp. at Base Aerea Jara was 30.6C this is the highest minimum temperature ever recorded in September in the whole Southern Hemisphere. pic.twitter.com/LLRX0KXjx0— Extreme Temperatures Around The World (@extremetemps) September 4, 2023

Part of the reason is that the oceans that typically keep big temperature swings in check have been really hot over these past few months. The Pacific Ocean is experiencing a strong El Niño this year, so warm water is moving west to east across the equator. This has the effect of heating up the ocean’s surface while channeling evaporation and rainfall. The ripple effects of El Niño tend to heat up the whole planet. The Atlantic Ocean also goes through temperature cycles and this year has reached record-high temperatures. The warm oceans have helped maintain warm air over the land in the Southern Hemisphere.

The background factor here is climate change. Average temperatures are rising all over the world and all throughout the year, but in general, winters are warming faster than summers. In fact, scientists say that higher temperatures in the cold seasons are a more robust indicator of humanity’s influence on the climate. “We can say with very high confidence that the recent warm seasons and weather contains a climate change signal,” Grose said.

Warm winters have important consequences

Hotter weather in the winter can have a lot of important consequences, even if temperatures don’t reach the triple-digit peaks of the summer. Plants, for instance, rely on temperature signals to time their life-cycles, and warmer winters throw this off. “We can say they are cuckoo, and not in a good way,” Gonçalves said. “It’s confusing.”

Specifically, as warm seasons get longer and cool seasons get shorter, plants can germinate earlier and grow longer throughout the year. This is a boon for some species, but it can create a misalignment for plants that need pollinators like bees if they blossom too early. It also leads to longer and more intense pollen seasons, creating misery for allergy sufferers. Warm winters can also change the timing of when plants bear fruit, which can affect the animals that depend on them for food.

Cold temperatures also keep dangerous insects in check, and the higher temperatures this year have allowed for more mosquito-borne diseases to spread in cities like Buenos Aires. “We had a dengue situation out of the season because dengue is more of a summertime problem here,” Rusticucci said.

Warmer, drier winters also mean that there is less water recharging rivers and groundwater supplies, and thus less water available for agriculture the following season. Hard, dry soil doesn’t absorb water quickly, so when rain does occur, it’s more likely to run off and create flash floods. And if it doesn’t rain, dry soil can lead to dust storms.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24907300/GettyImages_1547377730.jpeg)

Mauricio Zina/Bloomberg via Getty Images

This is all converging on top of other ways that humans have changed the environment. Dense urban areas like São Paulo and Buenos Aires form heat islands that trap more heat than surrounding areas. And deforestation of critical rainforests like the Amazon has disrupted vital rainfall patterns, worsening droughts, increasing regional warming, and creating conditions for wildfires.

A warm winter in the Southern Hemisphere can have global impacts too. The reduced sea ice around Antarctica can alter ocean circulation patterns, changing the flow of vital nutrients needed to nourish fisheries. Sea ice also shields ice on land, so losing it can cause ice sheets to melt more. That in turn can contribute to sea level rise along shorelines around the world.

Spring and summer will only get hotter down south

Researchers expect that the factors that heated up the winter across the Southern Hemisphere will continue to play out and amplify over the next few months as the seasons change. “In fact we expect the biggest effect of the El Niño to emerge as it fully forms and then plays out over coming months and into next year,” Grose said. The Indian Ocean Dipole, another ocean cycle, is also moving toward its positive phase, which tends to reduce clouds and rainfall over Australia. “In Australia, the warm winter was a new record and the seasonal forecast is for a warm spring as well,” Grose added.

In South America, the warmer season will also bring more precipitation, likely in torrential downpours. During past El Niño years, countries like Paraguay and Uruguay experienced deadly flooding, so the region is anticipating similar or worse conditions. “We will probably have a hot summer and a rainy summer,” Gonçalves said.

As a result, more weather records are poised to fall this year as the planet continues to experience what will likely be the hottest year ever recorded. Figuring out all the ways this will affect us is, as scientists like to say, an “active area of research.” We’re learning in real time what happens when the world reaches an unprecedented state. And with the climate changing, humanity will see more changes it has never witnessed before.