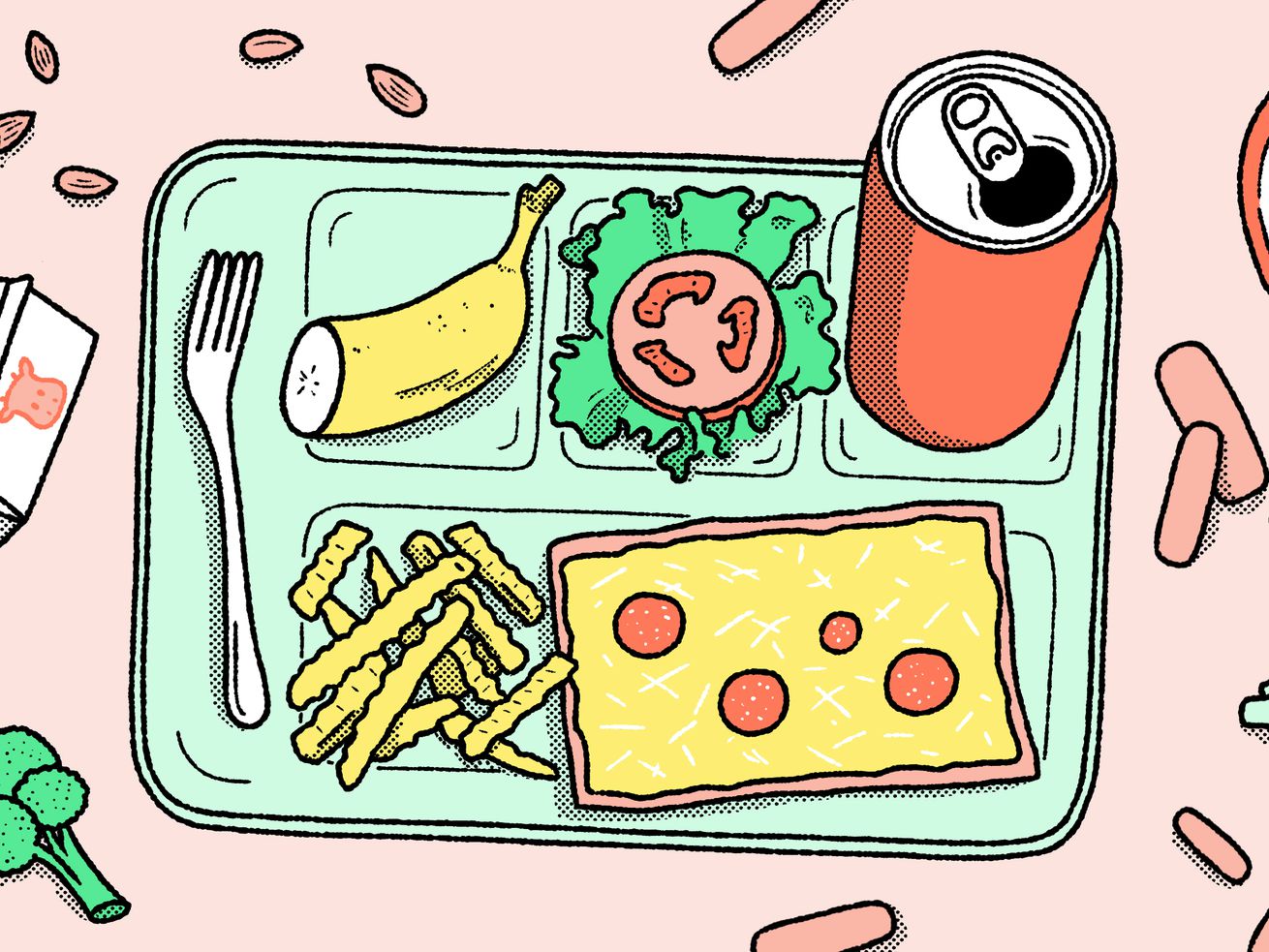

The fascinating history behind why students today are still eating square pizzas, crinkle fries, and cartons of milk.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21899595/VOX_The_Highlight_Box_Logo_Horizontal.png)

Part of The Schools Issue of The Highlight, our home for ambitious stories that explain our world.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726140/1_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726464/2.jpeg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726145/3_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726146/4_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726147/5_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726148/6_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726150/7_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726152/8_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726154/9_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726155/10_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726157/11_12_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726159/13_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726160/14_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726161/15_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726162/16_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726163/17_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726164/18_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726165/19_20_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726166/21_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726167/22_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726169/23_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726170/24_copy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22726173/25_27_copy.jpg)

Sources:

Revenge of the Lunch Lady, HuffPo

An Abbreviated History of School Lunch in America, Time

School Lunch infographic, Advancement Courses

Revolution at the Table: The Transformation of the American Diet, Harvey Levenstein

PBS The History Kitchen: History of School Lunch

Is whole milk illegal in New York?, PolitiFact

No Appetite for Good-For-You School Lunches, The New York Times

USDA on NSLP

Ally Shwed is a cartoonist and visual journalist whose work has appeared in The Boston Globe, The Nib, and The Intercept. She lives in Belmar, NJ with her cartoonist husband and their two cats.

Author: Ally Shwed

Read More