Interrogating the “online hot girl” persona.

My jaw clench is back. It was around during the week of the election, in that several-day stretch where the poor CNN guy had to point at the same map for 72 straight hours. It returned in the lead-up to my birthday party, and now it’s back and I’m not really sure why, which is its own kind of anxiety. But that’s okay, because on the internet, I can tweet something like “hot girls have bruxism” and maybe get 50 or so likes.

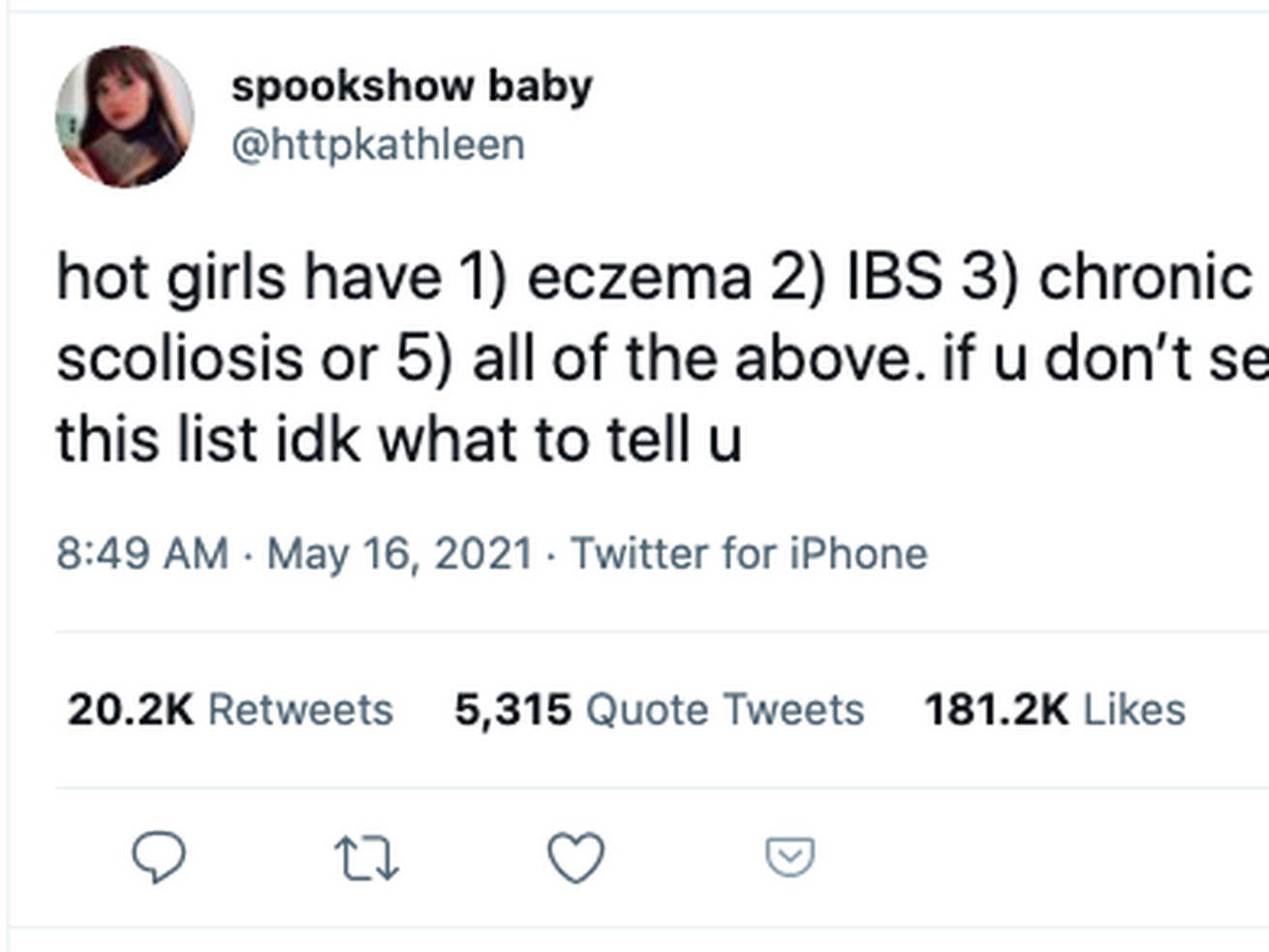

This is how it feels to be on the internet lately. You’ve potentially seen some iteration of this, perhaps in a tweet about how all hot girls have IBS and depression or anemia and ADHD or some combination thereof. The joke, of course, is that these are deeply unhot ailments, couched in the acknowledgment that yes, I too am in on the joke, unlike you other weirdos who won’t stop earnestly debating the scraps of whatever the culture war most recently dredged up.

But before we got to a place where we were openly talking about hot girls’ bowel movements or their collective proclivity for, like, tinned fish, there was Megan Thee Stallion. In 2019, the artist’s fans iterated on her “hot girl” moniker and invented the concept of “hot girl summer.” At the time, the idea that people of all genders could call themselves hot girls because they shared a certain attitude and not because it had anything to do with their proximity to traditional hotness, felt novel. Even Megan certainly couldn’t have anticipated what came next, though, which was the total memefication of “hot girl” by too-online adult women, creating something like a natural, more self-aware nemesis to the girlboss.

hot girls have 1) eczema 2) IBS 3) chronic utis 4) scoliosis or 5) all of the above. if u don’t see yourself on this list idk what to tell u

— spookshow baby (@httpkathleen) May 16, 2021

One of my favorite TikTok memes from a hundred years ago was “I can’t talk right now, I’m doing hot girl shit.” There was one iteration that made me gasp in recognition: In this instance, the “hot girl shit” in question was “scraping the large mounds of dandruff off my scalp,” which is objectively disgusting but extremely relatable to me personally. “‘I’m hot’ is the new ‘I’m ugly,’” reads a recent tweet from the delightful @clintoris, referencing the wave of people calling themselves ugly on the internet, but, as I’ve written about previously, in an almost wholesome or progressive way.

When I talked to an expert for that story, she said that the inclination to self-deprecate is mired in self-protection. “I kind of celebrate what they’re doing — they’re trying to push back on the idea that we all look perfect on social media,” Sara Frischer, a psychiatric nurse practitioner, told me. “But I think it’s just a little misguided in how they’re doing it. It’s deflection, and it’s self-protective to then make a joke about it. It protects people from feeling vulnerable.”

Calling yourself a hot girl would appear on its face to be the opposite: Rather than reappropriating a weakness, you’re asserting your power, regardless of how traditionally attractive you actually are. There’s something else going on, though, something more like how a humblebrag operates as a way of protection against seeming too narcissistic. You can use the specter of hotness as a preemptive defense against any anonymous avatars waiting for the chance to call you ugly or fat, while also adding the vulnerability of admitting you have poop problems.

That’s a relatively cynical explanation for something that, again, is literally just a joke. Yet I’d argue that “sad online hot girl” is just as useful of an identity marker as anything else. The popularity of the ironic bimbo aesthetic — the state of being both classically hot and socially progressive — has given way to a continuous debate on TikTok and elsewhere about whether it’s really possible to be a feminist while still appealing to the male gaze. But as Marlowe Granados pointed out in the Baffler, the feminist film scholar Laura Mulvey’s theory of the male gaze was about representation of women in art created by men, not actual women living their lives. “Laura Mulvey’s manifesto has been recast as an inescapable fact of life, conflating men’s artistic gaze with men’s literal gaze — the latter being painted as inherently oppressive,” she writes. “How long will we measure women’s every action against the Male Gaze?”

The idea of proudly touting oneself as a hot girl subverts not only men’s opinions, but the opinions coming from the endless annoying chatter of circular internet discourses. Every time I come across a video about whether, say, plastic surgery is inherently progressive or immoral, I’m reminded of why so many of us wish we were hot sluts who don’t know how to read. It’s because watching the same kind of people — people who seem to have genuinely good intentions but have spent far too much time arguing in comments sections — yell over each other is exhausting. “Hot girl,” then, is a relatively useful term for the very online to differentiate themselves from, well, the other kind of very online person.

Regardless, calling yourself a “hot girl” is normal now. But wait: Next we’ll all be calling each other “submissive and breedable.”

This column first published in The Goods newsletter. Sign up here so you don’t miss the next one, plus get newsletter exclusives.

Author: Rebecca Jennings

Read More