… And why that’s a problem.

My parents were in New York City this month visiting two of their four children. Given that my mom enjoys shopping and air conditioning but bemoans walking, we have developed the strategy of taking her to areas where we can maximize the shopping and the distance in between.

During one of our excursions, I noticed that J.Crew had a rainbow flag in its window. So did the new Nordstrom’s men’s store. Bloomingdale’s has a pride section. The SoulCycle I visited earlier in the morning had a rainbow sign proclaiming “All Souls Welcome.” McDonald’s has rainbow french fry containers. And H&M, Nike, and Lululemon all had signs or merchandise, too.

The symbolic support for the LGBTQ community is ubiquitous, particularly during Pride Month. The list of causes with more visible support is short.

But what exactly are these stores and brands supporting? More important, what happens to the money we spend in these stores? Does brand support for LGBTQ issues have any real impact, or is it just, well, branding?

Take, for example, Adidas, which has a special section of its site called the “pride pack” selling rainbow merchandise to honor Pride Month. But it’s also one of the major sponsors for this year’s World Cup, which takes place in Russia, a country with anti-LGBTQ laws that make it unsafe for fans and athletes. That contradiction throws into sharp relief the emptiness that can lie at the center of corporate gestures of “support” for the LGBTQ community.

Alexander Ryumin/TASS via Getty Images

Alexander Ryumin/TASS via Getty ImagesAs the general support for LGBTQ rights grows, so does the corporate incentive for brands and companies to position themselves in sync with that growing sentiment. But in that commercialization lies the disconnect: Brands promoting gay pride and the LGBTQ community may not always be consistent in actually supporting the LGBTQ community, but they still capitalize on the help that people want to give that community. It brings into question what Pride Month means, where it came from, and what we really commemorate when we celebrate it.

What Pride Month really celebrates

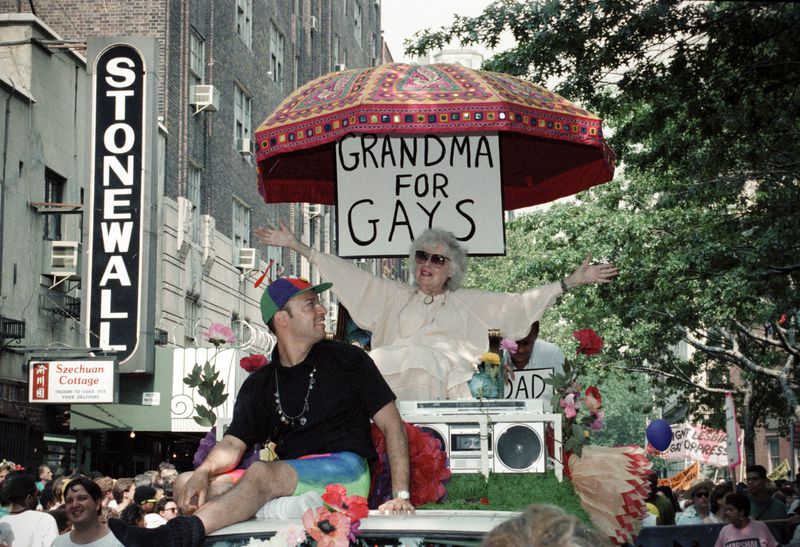

Pride Month, pride celebrations, and pride marches are how LGBTQ people and allies address the ongoing work for acceptance and equality, which ultimately brings us to the Stonewall Riots of 1969 in New York City. Fed up with being harassed and targeted, LGBTQ patrons of the Stonewall Inn, who were predominantly people of color, fought back against the police. It resulted in four nights of rioting.

“Before Stonewall, gay leaders had primarily promoted silent vigils and polite pickets, such as the ‘Annual Reminder’ in Philadelphia,” Fred Sargeant, one of the original organizers of the march, wrote in the Village Voice. “Since 1965, a small, polite group of gays and lesbians had been picketing outside Liberty Hall. The walk would occur in silence. Required dress on men was jackets and ties; for women, only dresses. We were supposed to be unthreatening.”

Stonewall, spurred by the frustration of being targeted and harassed, worked where polite and civil protests had failed. The first Pride march took place in 1970, a year later, to commemorate — loudly and without a dress code — those who fought for their rights.

Thanks to those Stonewall patrons and generations of LGBTQ people who fought for the rights of the community, the world is now an easier place to live for LGBTQ people than it was 10, 15, or 20 years ago.

Sergio Florez/AP

Sergio Florez/APBut those advances in LGBTQ acceptance create an odd dynamic, since pride celebrations were originally a strongly political act born of a time when tolerance still hadn’t been won. The ostensible goal of the Stonewall riots and pride events is to make the world a place where LGBTQ people don’t need to fight for rights. Subsequently, one of the biggest criticisms that’s grown up with pride celebrations across the country is that they’ve become more about the party (in part because of the progress made) than the politics. And it’s a hell of a lot easier to commodify a party than it is a political act.

For example, in New York City this year, the Pride Island celebration — featuring musical guests and Skyy vodka sponsorship — is selling a cabana package for $3,000. And as the New York Times reported, in 2016 Los Angeles pride was referred to as “gay Coachella” — and this year, Los Angeles Pride organizers got into trouble for over-selling tickets to the festival and had to turn hundreds of paying celebrants away.

That’s not to say pride events have been completely stripped of politics. In fact, due to the Pulse nightclub shooting in 2016 and President Trump’s anti-LGBTQ policies, 2017 was actually considered one of the first years in recent memory where politics became a central message of Pride celebrations across the country. As with the Stonewall riots and the first Pride, the twin threats of violence and oppression toward the LGBTQ community underlined the ongoing necessity of Pride Month as a political act first, a party second.

Brands and Pride Month take advantage of activism and slacktivism alike

To grasp the dilemma of the commercialization of pride events, it’s worth examining a very similar case: the “pinkwashing” of Breast Cancer Awareness. The phenomenon of any kind of pink object coming to represent “awareness” of breast cancer created a context where purchasing pink anything and everything allowed people to feel like they were contributing somehow to a cure for the disease.

But the problem with Breast Cancer Awareness, as Jezebel and many others pointed out, is that all this commercialized support was ultimately pretty empty. In 2015, the New York Times explained that for all the awareness, “breast cancer incidence has been nearly flat and there still is no cure for women whose cancer has spread beyond the breast to other organs, like the liver or bones.”

“What do we have to show for the billions spent on pink ribbon products?” asked Karuna Jaggar, the executive director of Breast Cancer Action, an activist group, told the Times. “A lot of us are done with awareness. We want action.”

This is the problem with commodifying “awareness”: While it may serve to raise money for a charitable cause, there’s no guarantee that money will result in any sort of tangible outcome. It’s nominal activism divorced from real action.

The same goes for much of pride merchandise. Companies, including H&M, donate a portion of what their customers spend on pride merchandise to LGBTQ charities. The amount going to charity varies by the company and product: J.Crew donates 50 percent of the purchase price of its pride T-shirts; H&M only donates 10 percent of the sales from its “Pride Out Loud” collection. Nike’s website doesn’t say how much of the proceeds from its Be True campaign the company donates, but it does say that Nike has donated almost $2.7 million since 2012.

So money going to LGBTQ charities is a good thing, right? In the abstract, yes, but taken in aggregate, this consumerist donation structure creates a context of so-called slacktivism, giving brands and consumers alike a low-effort way to support social and political causes.

Jenny Matthews/In Pictures via Getty Images

Jenny Matthews/In Pictures via Getty ImagesBut the money that companies make selling goods to people looking for an easy, straightforward way to help with a big, complicated issue rarely has tangible results, outside of the profits for the companies selling those goods. Similarly, some companies who are promoting LGBTQ Pride — and ostensibly cashing in on Pride merchandise or retail — aren’t doing much for the LGBTQ community beyond contributing to this vague notion of “awareness” around the issues that affect that community.

Los Angeles Pride selling more tickets than it had space for is just one example. The rainbow-festooned H&M having a manufacturing plant in China, a country with a history of anti-LGBTQ legislation, is another.

Perhaps the most pertinent example is Gilead sponsoring New York City Pride. Gilead is the pharmaceutical company that makes the pill Truvada for PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, a medication regimen that, when taken daily, can reduce the risk of HIV from sex by over 90 percent. Without insurance, PrEP costs me $2,110.99 per month; with insurance and a coupon card from Gilead, that goes down to zero. The problem is that the communities where PrEP can have the greatest effect aren’t getting the drug, because the people in those communities often cannot afford insurance that covers it.

“While the HIV epidemic has not had a broad impact on the general U.S. population, it has greatly affected the economically disadvantaged in many urban areas,” the CDC wrote in a study of poverty-stricken urban areas.

Further, gay and bisexual black men have a higher HIV rate in the US than in any country in the world. But they’re not the people using PrEP: According to Poz magazine, an estimated 136,000 Americans were using PrEP as of the first quarter of 2017, but a large majority of those users are white men who are 25 and older. Gilead Sciences estimated in 2015 about 75 percent of men who had filled a PrEP prescription were white, while black men only comprised 9 percent of those prescriptions.

Generic versions could change that, but Gilead won’t release its patent. Furthermore, as activists have pointed out, research and funding that went into Gilead were provided by taxpayer money, not money raised for “awareness”:

Imagine a pill that has the ability to reduce #HIV transmission by 99%. And what if you were told that all the funding that went into researching this preventative drug was actually by tax-payer money? #BreakthePatent (1) pic.twitter.com/Q6fbhrCbid

— Jason Rosenberg (@mynameisjro) June 18, 2018

Gilead publicly supports LGBTQ rights at one of the biggest LGBTQ celebrations of the year, but in practice it has not adequately served LGBTQ people who run the highest risk of contracting AIDS, a disease its drug could help prevent.

It’s also important to look at this phenomenon from the consumer perspective. If consumers who want to do more to help the LGBTQ community scrutinize and talk about what companies are doing with that money (e.g. the percentage given to charity versus what’s kept), or those companies’ inconsistent policies, it could help change the way companies — like Gilead — choose to “support” LGBTQ issues. Or consumers could do the work to research and seek out organizations themselves, making their donations directly and bypassing the retail element entirely.

But that raises what’s perhaps the most complex problem with supporting the LGBTQ community: knowing where to lend support. The ideal goal of Breast Cancer Awareness is to find a cure; all that pink stuff is bought with that goal in mind. But the “goal” for LGBTQ community isn’t one central thing, it’s a lot of different things.

Dennis Van Tine/STAR/AP

Dennis Van Tine/STAR/APSupporting the LGBTQ community is more complicated, since it’s not a monolithic entity, and there are myriad issues that affect different cross-sections of LGBTQ people. LGBTQ youth homelessness is an issue that persists and hasn’t gotten proper attention. Certain LGBTQ people are more at risk for being the victims of hate crimes (fatal violence disproportionately affects transgender women according to the HRC). LGBTQ people also face unique problems in the criminal justice system. And in some cases, the LGBTQ community itself hasn’t figured out how to come together to address and raise awareness for these causes.

And as Vox’s German Lopez pointed out, since the election of Trump and a Republican-dominated Congress, all kinds of anti-LGBTQ — and particularly anti-trans — actions, from trying to ban trans people from the military to rescinding Obama-era memos that protected trans workers and students from discrimination, have been introduced.

Perhaps the most frustrating thing about showing support during Pride is that there really isn’t one cause to support — blurring all these disparate issues under a one-size-fits-all rainbow means some are inevitably going to be overlooked. (See: how same-sex marriage dominated most conversations about LGBTQ rights prior to its passing.)

The commercialization of Pride Month adds another complicating layer to that, further flattening out the complex landscape of LGBTQ issues into an easier-to-support — and therefore easier to sell — concept of “awareness.” No doubt, the visible support from all these brands is welcome, especially in our time of Supreme Court cases over same-sex wedding cakes.

But it’s hard to shake the feeling that this commercialized mass appeal has helped further dampen Pride Month’s fiery political roots, and helped obfuscate the less-pleasant, less-talked-about issues that matter for many people in the LGBTQ community — and will continue to matter long after the rainbow T-shirts, socks, water bottles, and cute retail disappear from store windows.

David McNew/Getty Images

David McNew/Getty Images

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png