A far-right court just tried to ban an abortion drug. Here’s why you can ignore that decision.

On Wednesday, the far-right United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit handed down an opinion claiming that mifepristone, an abortion drug that has been legal in the United States since 2000, should effectively be banned, at least for several months. The case is Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. FDA.

The single most important thing to understand about this decision is that it has no effect whatsoever, at least for the time being. Mifepristone remains legal, and it will remain legal unless the Supreme Court signs on to this effort to ban the drug.

That’s because last April, after the Fifth Circuit launched a similar attack on this medication, the Supreme Court handed down a temporary order blocking this first attempt to restrict access to the drug. Notably, that April Supreme Court order provides that mifepristone will remain legal while this case works its way back to the justices. So, at least for the moment, the Fifth Circuit panel that heard the Alliance case is stripped of any power to ban the drug.

The legal arguments against mifepristone are wholly without merit. As attorney Adam Unikowsky, a former law clerk to the late conservative Justice Antonin Scalia, has written, “if the subject matter of this case were anything other than abortion, the plaintiffs would have no chance of succeeding in the Supreme Court.” And, given the Court’s April order, it does not appear likely that this case will succeed despite the fact that it involves abortion.

On its face, the Fifth Circuit’s decision does not purport to ban mifepristone in its entirety. Though the plaintiffs in this case — anti-abortion doctors and organizations that represent them — asked the court to do so, even the Fifth Circuit conceded that it lacks the authority to ban the drug outright. The FDA approved mifepristone for use in the United States in 2000, and the statute of limitations for challenging such an approval is six years.

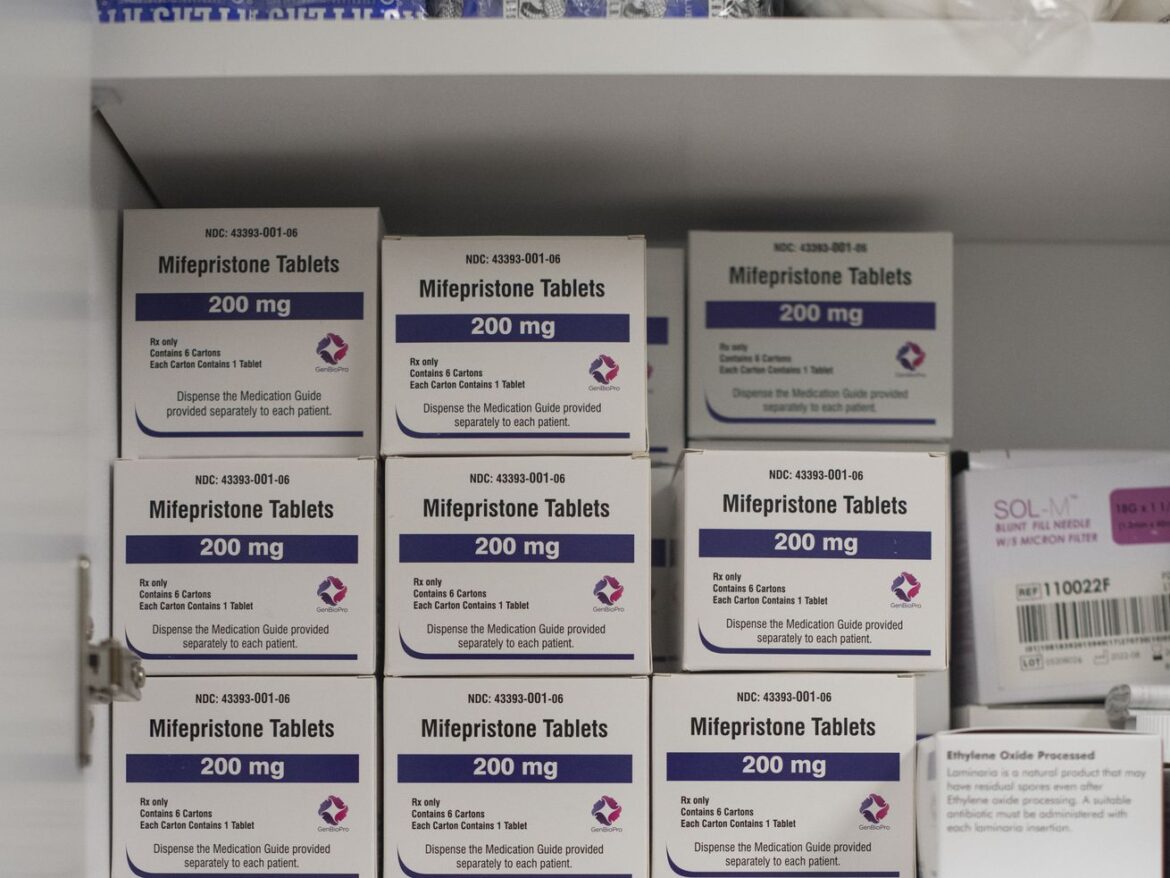

Instead, the Fifth Circuit’s decision claims that several changes that the FDA made to the protocol health providers must use when prescribing the drug, changes that the FDA began rolling out in 2016, are invalid. These include the FDA’s decision that mifepristone may be used up to the 70th day of a pregnancy, instead of just the 49th day, and a decision to reduce the amount of mifepristone dispensed to abortion patients (from 600 mg to 200 mg).

As a practical matter, however, requiring health providers to return to pre-2016 protocols will prevent them from prescribing mifepristone for at least several months. That’s because, as the drug’s manufacturer explained to the Supreme Court, the manufacturer must “revise product labels, packaging, and promotional materials; recertify providers; and amend its supplier-and distributor-contracts and policies” to comply with the old rules before the drug could be dispensed under those rules.

In any event, the Fifth Circuit’s decision, by Judge Jennifer Elrod, is 63 pages long but adds few new legal arguments that are likely to convince the Supreme Court to reverse course from its April decision. One of the most surprising aspects of Elrod’s opinion is that she devotes only three pages to one of the most important parts of her argument: the claim that the 2016 changes to the mifepristone protocol are invalid.

Elrod’s primary argument against these 2016 changes is that, while the FDA reviewed multiple studies concluding that mifepristone could be used safely under the new protocols, “none of the studies it relied on examined the effect of implementing all those changes together.”

But Elrod, who is neither a doctor nor a scientist, does not even attempt to explain why the FDA would need to review such a study before approving the new protocols. Nor does she cite any law mandating such a study. To the contrary, Elrod admits that the Supreme Court said, in Weinberger v. Hynson, Westcott & Dunning (1973), that the FDA must exercise “discretion or subjective judgment in determining whether a study is adequate and well controlled.”

Nevertheless, Elrod’s decision would strip the FDA of that discretion and give it to the judiciary.

Before the Alliance case was filed, there was broad bipartisan support within the judiciary for the idea that scientific judgments about which medicines are safe to be sold in the United States, as well as judgments regarding how those drugs should be dispensed, should be made by actual scientists in the FDA and not by lawyers in black robes. Indeed, in a 2020 dissent, Justice Samuel Alito chastised a lower court judge who “took it upon himself to overrule the FDA on a question of drug safety.”

When this case reached the Supreme Court last April, however, Alito dissented from the Court’s decision to keep mifepristone legal.

In any event, only Alito and Justice Clarence Thomas dissented from that order; seven justices voted to keep the drug on the market. So the risk that the Supreme Court will agree with Elrod is small.

Still, if mifepristone is to remain legal in perpetuity, the Supreme Court will need to hear this case once again. And it will need to reverse Elrod’s decision.