Michael Pollan on America’s broken — but improving — relationship with drugs.

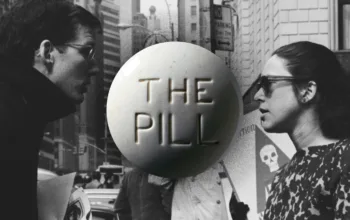

What makes a drug a drug?

It’s strange to say, but we don’t really have a good definition of the term. You could say a drug is any substance that transforms our subjective experience of the world, but food does that, too. So what’s the difference?

In this country, it turns out the difference is pretty arbitrary. Drugs are whatever the government says they are. And for a long time, the government has classified them in a deeply dishonest and cynical way. We call this absurdity “the drug war.”

But here’s the good news (especially if you’re one of the groups victimized by it): The drug war is dying. You can see it in the marijuana legalization movement and you can see it in the so-called psychedelic renaissance. The country will have to think seriously about what comes next. How will our taboos shift? What sorts of reforms will we need? What kind of cultural infrastructure should we build?

Michael Pollan is perhaps best known for his 2006 book The Omnivore’s Dilemma, but his 2018 work How to Change Your Mind did more than any other to vault psychedelics into the mainstream, and it remains one of the best explorations of the therapeutic potential of psychedelics.

Pollan’s latest book, published in July, is titled This Is Your Mind on Plants. This one is about psychedelics too, but it’s a much broader look at our all-too-human obsession with psychoactive plants — not just hallucinogens but also caffeine and opium — and why our culture has such a fraught relationship with them.

So we talk about all that, and we explore what we can learn from other cultures about how to use psychedelics, and why he thinks these plants are powerful antidotes to our disconnected lives.

You can hear our entire conversation (as always, there’s much more) in this week’s episode of Vox Conversations. A transcript, edited for length and clarity, follows.

Subscribe to Vox Conversations on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Sean Illing

I’ll start with a deceptively simple question: What is a drug?

Michael Pollan

It’s deceptively simple because it’s very hard to say. I think of it as something we ingest that changes us in some way, but of course you could also say that about sugar or chicken soup. I went to the Food and Drug Administration, who you’d think would have nailed this down a long time ago, but they basically decided that a drug is a “substance” that is not food that is called a drug by the FDA. That’s how they define a “drug.”

Sean Illing

It’s still not at all clear to me what makes a “drug” a drug and food food.

Michael Pollan

There are a lot of cases right on the edge. Sugar is a great example. If you’ve got kids and you’ve watched how they respond to sugar, there’s no question it’s a drug. But then what about a placebo? That is something that you ingest that changes you, but it’s not a drug in the pharmacopeia. So it’s a mess. All of this shows that there’s something very arbitrary about illicit versus licit drugs. An illicit drug seems to be whatever the government has decided is illicit.

Sean Illing

We’ll get to that, but let’s step back a little. Humans have always — and I mean always — loved drugs. Why do you think we’re so determined to change our own consciousness? What is it about ordinary states of consciousness that bores us or scares or limits us?

Michael Pollan

I’ve been interested in this question for a very long time, as long as I’ve been writing about the relationship between plants and people. It’s very curious that this appears to be a universal desire of our species to change consciousness, that we’re not satisfied with everyday normal consciousness. You alluded to one reason, which is boredom. I think that people seek novelty, and they seek novelty in states of mind as well as places and activities, so that’s one.

The relief of pain is another, and that’s one of the most important things we’ve used drugs for. For most of the history of what we now call medicine, pain relief was about all you could get out of it. Opium was the greatest drug in the pharmacopeia because it could relieve pain. And other drugs, whether they act directly on pain or not, distract you from pain, and that’s often just as good. Cannabis works that way for some people. It doesn’t really diminish pain, but at certain doses you just don’t give a shit about the pain.

But I think that there are more interesting reasons that we use drugs. One is, the novelty they contribute is useful to us as a species. The way I describe it in the book is that they’re mutagens in a cultural sense. In the same way that mutations in DNA lead to variation and every now and then produce useful traits that then give an advantage to the individuals or the species that acquire them, drugs have a similar mutating effect on cultural memes. They give people ideas, they plant metaphors, images, all these things that feed into cultural evolution in a way similar to the way mutation and variation feed into biological evolution. That’s pretty speculative, and I don’t know that I could prove it scientifically, but I think that’s part of what’s going on.

The other important things that drugs do is increase sociality. Drugs like alcohol make people more fluid socially, more interested in other people. MDMA does this, too. Activities that make us more sociable creatures are very important to our success as a species.

Sean Illing

Our popular conception of drugs seems so flat in comparison to what you’re saying now.

Michael Pollan

During this last 50 years of the drug war, we’ve lost track of this. We’ve really simplified our view of drugs into good and evil. We tend to moralize them, and we’ve lost track of the fact that something that could be dangerous used in a certain way could also be incredibly helpful in another way.

The Greeks really got it with their word for drugs, they called them “pharmakon.” That could mean both a blessing and a curse depending on the context, and context is everything when it comes to drugs. There was also a third meaning of pharmakon, which was something like “scapegoat.” That’s very revealing. A drug was something you could blame things on. And God knows we’ve done that.

Sean Illing

I’d argue that our most incontestable right as human beings is the right to experiment with our own consciousness, with our own minds. Why do you think the state is committed to policing how and whether we do this?

Michael Pollan

I think it’s because the state regards drug use as a tremendous threat. There are certain drugs that contribute to the smooth working of society, like coffee today. But I wrote about coffee in the book and there were lots of problems when coffee first showed up in Europe. King Charles II wanted to ban it briefly because he didn’t like all the political conversation going on in the coffee houses. He felt threatened. He thought it was a seditious beverage, but that didn’t work. It was already too popular and he backed down.

In general, though, a drug like caffeine is making us better workers, more focused, less drunk. It’s a great drug for capitalism. Capitalism loves caffeine. You need no better proof of that than the existence of the coffee break as an institution. Here’s a case where your employer gives you a drug free of charge and then gives you paid time in which to enjoy it. That’s all you need to know about who’s benefiting from caffeine.

But then you have something like LSD or psilocybin, which the government took a very strong interest in, even though they’re virtually non-toxic and non-addictive. But they were disruptive to society in the ’60s. Nixon believed that the reason young boys weren’t willing to go to Vietnam was because of drugs and specifically because of LSD. It may have contributed to their willingness to defy authority. These are substances that, taken in the right context, do encourage independent thinking of various kinds.

Here was a rite of passage, but, unlike most rites of passage, LSD didn’t fold the person more tightly into society. It had the opposite effect. It made this young person feel that they were in a whole other culture and wanted to dress differently, talk differently, have different mores. We called it the generation gap. And you had this very interesting and historically pretty novel split in the values of two different generations.

When Nixon decided to launch the drug war in 1971, he did it because he thought these drugs were threatening his political agenda — and he may well have been right.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22717010/9780593296905.jpg)

Sean Illing

Oh, he was most definitely right, and it speaks to a broader point you were hinting at earlier: One way to determine what a society really values is to look at the drugs it condones and condemns. And it’s awfully revealing that our society says bourbon and caffeine are good but somehow DMT or psilocybin are bad.

Michael Pollan

Yeah, but it’s very interesting that those same chemicals are good in other cultures in other contexts. For example, one of the reasons I was so interested in writing about mescaline is that it’s a psychedelic like LSD, but the way it’s used in the Native American church, where it’s a legal sacrament, is the most conservative way imaginable. It is used to enforce social cohesion and help heal traumas. It’s this very conservative model of psychedelic use. And that told me that there’s nothing inherently disruptive about psychedelics — it’s how they’re used.

Sean Illing

That will surprise a lot of people. Can you say a bit more about how a drug like mescaline is used to reinforce, as opposed to disrupt, social bonds and values in these communities?

Michael Pollan

Well, the indigenous use of psychedelics goes back at least 6,000 years. That’s the oldest evidence we have for the use of mescaline in the form of peyote, the cactus that produces mescaline. These cultures have had a lot of time to experiment with these drugs and figure out what they’re good for. And in most of them it’s always a social application. They don’t use psychedelics alone. It’s always in a group setting and they’re approached with great solemnity and ritual, which I think is incredibly important. They don’t use these drugs (or medicines) for thrills. It’s for communal healing.

Sean Illing

Why didn’t that happen here?

Michael Pollan

One of the most striking things about psychedelics is when they showed up in the West, beginning with Albert Hoffman’s discovery of LSD in 1938, they were novelties. We didn’t look to traditional cultures to understand them, probably out of condescension. So these powerful substances arrived without an instruction manual.

So we just started that process of trial and error that other cultures may have gone through 10,000 years ago. We began in the ’50s and ’60s, and there was a little bit of research into their potential as medicines, but we didn’t know how to use them. We tried lots of things, and some of it was disastrous, and people got into serious trouble.

But now we’re in the midst of this renaissance in psychedelic research, and it’s leading to new ways to use these drugs therapeutically that I think the government will actually support very soon. That’s a huge turnaround. And maybe that will change our understanding of psychedelics from something that disrupts our society to something that helps smooth the operation of society, because right now mental health difficulty is what’s disrupting our society.

Sean Illing

Well, the good news is that the dumb taboos created by the drug war are dying and the laws are starting to evolve, which raises the question: What comes next? How do we fold these substances into society?

Michael Pollan

That’s a fascinating question. What does the piece look like after the drug war? I don’t have the answers but I have some glimmers of answers. I think that in a way the drug war made things easy, because we didn’t have to have this conversation — it was either the drug was illegal or it was legal and we let the government decide. These questions will fall to individuals and cultures when the drug war ends.

One of the really interesting developments to watch is the formation of these new psychedelic churches, around psilocybin or DMT or ayahuasca. They’re popping up all over the place. People are forming churches because they think it’s going to give them some legal protection, and it may. The jurisprudence of the Supreme Court around religious freedom is so expansive that it’s going to be an exploding cigar in front of Sam Alito or John Roberts when the court has to consider the rights of the Church of Lysergic Acid or something. They’re going to be hard-pressed, given the precedents that they’ve laid down.

Sean Illing

A theme in this book and your last one is that human beings have become too separated from nature. I obviously agree and I’d argue that this is maybe the most consequential fact of the post-industrial world. Are you still hopeful that a psychedelic renaissance is at least part of the solution to this problem?

Michael Pollan

Look, all my writing has been about bringing nature back into people’s lives and realizing how plants affect us and how we affect them. That reconnection is a big part of my life. Our distance from nature, which is even more pronounced in younger generations who’ve grown up with social media, is an enormous threat. And I’m really interested in any research that explores whether psychedelics help with that. I do think psychedelics are an antidote to our mediated lives and our addictions to phones and screens and everything else that comes between us and the natural world.

Psychedelic takes you off screens. Your phone is not going to be part of the experience, and it is very much about reconnecting to the body, to the contents of the mind, to your memories, and to nature. I had very profound experiences in nature on some of my psychedelic experiences. But again, I was already well-disposed as a gardener to love my plants. What I wasn’t ready for was to have my plants return my gaze in the garden and announce themselves to me in a way they never had before, as agents with their own perspective and subjectivity. I know this sounds absolutely crazy, but my plants were more alive than they’d ever been.

These are products of nature. This is nature talking to us. And yes, LSD was invented in a lab, but it’s based on a chemical produced by fungus. It’s extraordinary that the plant world might be offering us an antidote to the flight from nature. These plants call us back to nature, and nothing seems more valuable right now than something with that power.

Author: Sean Illing

Read More