Experts say curfews could backfire. Here’s why.

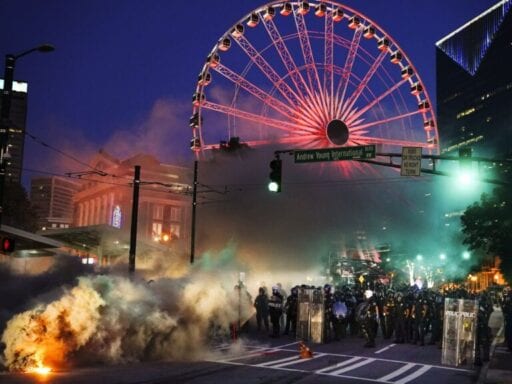

Local officials have ordered curfews in dozens of cities and counties across the nation in response to demonstrations spurred by the death of George Floyd, an unarmed black man killed by police during an arrest in Minneapolis last week.

These protests have grown in size and intensity in the days following Floyd’s killing; although they have largely been peaceful, some looting, property damage, and a number of deaths led officials in at least 39 cities and counties across 21 states to institute curfews. But some criminologists have reservations about curfews, particularly given the scarcity of research about their effectiveness — and warn the curfews currently being instituted could backfire.

In many cities — including Minneapolis, Salt Lake City, Reno, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles — protesters defied those curfews on Saturday, meaning protests, including some featuring violence on the part of police and agitators, continued. And that police made arrests not only for criminal acts like theft and arson, but also for violating curfew.

In some cities, those who stayed out were allowed to continue their protests; in others, however, defying curfews led to aggressive behavior from police, like in Minneapolis, where police fired rubber bullets at demonstrators and journalists. The fact that some of Saturday’s curfews provoked this violent police response, and that other curfews were completely ignored, raises questions about the wisdom and efficacy of ordering a curfew in the first place.

It is unclear whether ordering emergency curfews — that is, telling people they must stay at home and avoid public areas after a certain time in the evening, and increasing public police presence to enforce it — is effective in reducing unrest. Criminologists note there doesn’t appear to be an abundance of research on the matter. But some experts have raised concerns about the way curfews are likely to be enforced in communities of color, and argue they could exacerbate the very dynamics that gave rise to the unrest in the first place: Namely, that they will encourage confrontational policing at a time when people are demanding the opposite.

“What we know is curfews increase opportunities for police interaction and police violence over time,” Andrea Ritchie, a criminal justice researcher at the Barnard Center for Research on Women told me.

The surge in curfews and increased deployment of law enforcement officers over the weekend — some of which extend through Monday morning — reflect an intensifying effort by government authorities to curb the protests that have rocked the country for days and have revived an ongoing discussion about racial discrimination in the American criminal justice system.

The curfews that most local officials have sought have been extremely short-term — some began on Saturday at 8 pm and ended at 6 am Sunday. But others resume on Sunday night and last until Monday morning. Should unrest continue in the coming days or weeks, it’s possible a number of government officials will turn again to curfews — and some experts are concerned about how they could be enforced.

Curfews are a “blunt tool” for trying to reduce turbulence

While there is a great deal of scholarship on the efficacy of extended juvenile curfews on reducing crime in the US, that same breadth of research does not exist on sweeping, short-term curfews, according to experts.

William Ruefle, a scholar of criminology at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg, told TIME in 2015 that there’s been very little research into the topic, and that does not appear to have changed in the last few years. Alex Vitale, a professor of sociology and the coordinator of the Policing and Social Justice Project at Brooklyn College, told me he “[doesn’t] know that there is a lot of research on emergency curfews during rioting.”

But Vitale did note that there are a number of widely held concerns about the effect curfews have on the public.

“Curfews are an extremely blunt tool that should only be used sparingly and as a last result. They give police tremendous power to intervene in the lives of all citizens,” he said. “They pose a huge burden on people who work irregular hours, especially people of color in service professions who may need to travel through areas of social disturbance in order to get to and from work at night.”

Vitale also noted curfews are often enforced by officers from multiple jurisdictions — like state police and the National Guard — who “may have no familiarity with these communities” they’re sent in to police, which could lead to unnecessary tensions or violence.

They may, for example, not be attuned to the kinds of hours that people in a given area work or what normal patterns of public movement are like there — useful knowledge, since not everyone will get the memo that there is a curfew in effect. That in turn means police could arrest people who have no intention of defying a curfew.

Examples of the negative, even dangerous, interactions with law enforcement that curfews can create went viral Saturday night. In Minneapolis, critics have posted videos of police officers who appeared to be enforcing the curfew overzealously. Tanya Kerssen, who lives in the city, tweeted that the officers shot paint canisters at her while she was on her own porch, while shouting “light ’em up.”

Share widely: National guard and MPD sweeping our residential street. Shooting paint canisters at us on our own front porch. Yelling “light em up” #JusticeForGeorgeFloyd #JusticeForGeorge #BlackLivesMatter pic.twitter.com/bW48imyt55

— Tanya Kerssen (@tkerssen) May 31, 2020

Ritchie, the Barnard researcher, is deeply skeptical of curfews — which put more police on the street, and empower them to behave repressively in a tense situation — as an effective policing mechanism when animosity toward police is fueling the protests in the first place. “If the source of uprising and resistance is police brutality, then imposing a curfew that creates more opportunities for police brutality is definitely not the answer,” she said.

Ritchie pointed out that during the Detroit protests in the summer of 1967, which began after a police raid on an unlicensed bar, “alleged curfew violations were the basis of police killings and much police violence.” After protests end, events like this are remembered, and only increase friction between police and communities, particularly communities of color.

She also argued that in the context of the coronavirus pandemic, mass arrests under a sweeping curfew order represent an inappropriate kind of overreach that could exacerbate public health crises.

That is of particular concern as the US struggles to contain the coronavirus pandemic. Arrests could lead to extra financial burdens during a period of economic downturn, and increase the risk of Covid-19 spread in jails and police stations. Not to mention that at least some arrested for curfew violations come from the black and Latino communities hardest hit by the pandemic.

And critics argue the haphazard way many government officials have been going about imposing the orders also has the potential to disproportionately harm the poor and people of color.

For example, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot gave merely 35 minutes’ notice to the public when she announced a curfew on Saturday for 9 pm. Many — including the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois — pointed out that it was unfair to issue the order while public transportation was suspended, restricting the ability of Chicagoans to get home quickly. Lower-income people who can’t afford to call a ride hailing service are particularly likely to be vulnerable to arrest in such situations.

Local government officials, on the other hand, see curfews as a tool for maintaining order when protests threaten to spiral out of control and create property damage or deaths. When explaining her abruptly issued curfew, Lightfoot said the protest “situation has clearly devolved, and we’ve stepped in to make the necessary arrests.”

In some cases, the threat of arrest could work short-term in persuading certain protesters to get off the streets. But when curfews result in confrontations between police and the people — whether they’re out deliberately or caught by accident — it’s likely to cause long-term damage to community trust in police.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Zeeshan Aleem

Read More