The 1968 government-sponsored report reveals that demands from activists around policing are nothing new.

Half a century ago, the nation sat in a familiar place.

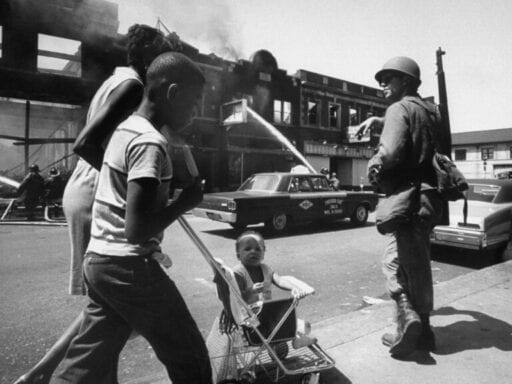

Then, as now, cities burned from police violence (the poet Amiri Baraka had a phrase for it: “white cop Black death syndrome”). Watts, Harlem, and Rochester in 1964 and 1965. Ferguson, Baltimore, and Charlotte five years ago. Dozens of cities just weeks ago.

Then, as now, the Black communities who stood at the brink of all of the harms of an unreconstructed democracy knew to be wary. That in the smokescreen of building new constitutional safeguards and procedural policing reforms and new techniques to improve policing, we were quietly constructing the conditions for even more police power. Just after Black communities rose up against police brutality in city after city in the 1960s and early 1970s, police power grew tremendously, with most major police departments doubling in size, and arrests among Black Americans doubled.

Then, as now, Black people called for the right to control the means through which their communities are protected. Then, as now, they sought other means of protection that would not resort to policing and punishment. It should have been taken seriously then, but it wasn’t. It must be now.

Some signs have pointed to the partial realization of current demands: The Minneapolis City Council voted unanimously to “dismantle” the Minneapolis Police Department earlier this month, and heed the community-run public safety solutions proposed by organizers. The mayor of Los Angeles has proposed cutting $150 million from the LA Police Department, and several school districts including Denver and Seattle intend to remove police from their schools. Also since the protests began, San Francisco announced that it would no longer send out police for concerns around homelessness, school discipline, neighborhood disputes, and mental health issues.

However, calls to defund or abolish the police have also been met with backlash, and some media and policymakers have characterized these calls as new. What they’re missing is that a half a century ago, even the US government itself sought to document these demands, and the lived experience of policing that gave rise to them, and inscribe them in policy.

Interviews revealed intense distrust for the police among Black communities

Following the uprisings of summer 1967, a little-known but extraordinary effort to collect a grassroots experiential critique of policing took place. A research team of 40 investigators, many of whom were young liberal men returning from the Peace Corps, was formed by Lyndon B. Johnson’s Kerner Commission; they were charged with investigating the causes of and necessary interventions to addressing Black discontent. They fanned out across neighborhoods in 10 cities to interview hundreds of Black residents, activists, and community group leaders. Each research team had at least one Black investigator who interviewed most of the Black community members in the study. One can still read their notes on the interviews, including hand-scribbled comments about each interviewee (“local Negro militant” read one; “Negro barber” read another).

The commission’s field team not only summarized the causes of the rebellions, they learned how the Black community had already been organizing to protect itself from police violence, to set up autonomous structures to create opportunities for youth, and to gain control of the white-led institutions that were failing them. They heard of the frustration that when their communities pursued local control in response to state neglect, the state would see them as overstepping and quash their efforts.

Karl Gregory in Detroit, for example, told the commission’s field interviewer that “neighborhood groups attempted to organize and develop a program to deal with particular problems [with police brutality], [but] they could never get the program underway because they would spend all of their time defending themselves from police harassment.” Similarly, Rev. Charles Hunt in Cincinnati described how Black groups were uniting to seek actual control of the city and break the existing “plantation apparatus” that prevented Black leaders from having any meaningful say in the community.

Across these interviews, there’s an uncommon knowledge of how to understand the lived experience of police power and anti-democratic rule. A Detroit Auto Workers Union board member interviewed in the study described them this way: “Among whites in the suburbs, the police are servants to the people, whereas in the Negro neighborhoods, they are masters presuming guilt.” And liberation from police would not occur without Black self-determination.

The demands for community control and community-based efforts reflected in Kerner interviews were well underway by the 1960s. Local and national Black organizations demanded and often modeled a community-based alternative to traditional policing. They put forth a vision of public safety anchored by practices of Black communal care. Then, as now, they reframed police and jails not as institutions to fight crime but as instruments of oppression and as sources of, not solutions to, communal disorder.

Campaigns to decentralize police forces and put them under the democratic control of neighborhood councils took place in several cities. They developed community institutions to raise bail money in the Black community of Chester, Pennsylvania; provide drug treatment in a community-run wing of Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx; and operate community hotlines for the reporting of police attacks and neglect in LA’s Watts neighborhood.

These groups held public hearings in Washington, DC, and eventually set up a community-controlled police district there. They also initiated “defense and justice committees” and citizen review boards to track, investigate, and enjoin abusive police when their municipal governments did little. And in Seattle, Detroit, West Oakland, and even Minneapolis, community police patrols actively defended their neighborhoods against police abuse by monitoring police stops of residents, often taking it upon themselves to remind those under arrest of their rights, following them to jail, posting their bail, and filing complaints on behalf of those abused. Communities often came to see them as a protective force, “a guardian standing in the void left by official authorities and agencies.”

Such community control efforts were widely supported by the more radical and more conservative Black civic groups, as historians Simon Balto and Max Felker-Kantor have shown, including the Coalition for Community Control of the Police in Milwaukee; the Black United Front in DC and Boston; the League of Black Women and the Chicago Campaign for Community Control of Police in Chicago; the Coalition Against Police Abuse in Los Angeles; the Detroit Task Force for Justice; and even among groups connected to law enforcement like the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement and the Afro-American Patrolman’s League in Chicago.

But they were rarely, if ever, supported by people in power. A federal bureaucracy, the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA), delivered billions in funds to criminal justice institutions and especially police agencies during the 1970s; a mere 2 percent of the action funds went to community involvement in crime control. Though Black leaders in Congress fought to get the agency to fund local citizen groups for their public safety work and charged the agency with systematically denying funds to local Black groups, that aid bypassed almost entirely these community efforts and groups, going instead to groups like the International Association of Chiefs of Police. Worse, they were told through LEAA guidelines that to receive funds, they had to get the green light from police for their initiatives.

The idea of democratic, community control of the police has never been given serious attention. Instead of true community authority over police in their neighborhoods, Black communities received enhanced representation on the police force. Power and authority was never shifted to the communities being policed. It was representation without control.

The findings of the Kerner Commission live on

The findings from the commission were rarely mentioned and largely forgotten in the ensuing years, even when the commission’s 50th anniversary was recently commemorated. But the voices therein are reincarnated in the protests today. Just as they had then, today those on the margins, those who endured the predatory policing in Ferguson, the awful conditions in Rikers, the boot on their necks in Minneapolis, have carried the appeal to freedom, breaking from the mainstream rhetoric of more training, more tactics, more technology, and — to support all of these — more funds. Increasingly, these efforts are led by queer Black women who have further adapted frameworks of community control and autonomy to be even more restorative, cooperative, and inclusive than before.

Take the Minneapolis-based Black Visions Collective, which formed in 2017 to organize for a future “where all Black people have autonomy, safety is community-led, and we are in right relationship within our ecosystem.” Or the Chicago Alliance Against Racist and Political Oppression, an organization founded in 1973 that continues to organize in coalition with grassroots groups for democratic control of the Chicago Police Department. Look to Dignity and Power Now, an LA-based grassroots organization founded in 2012 to fight for the “dignity and power of all incarcerated people, their families, and communities” guided by the principles of “abolition, healing justice, and transformative justice.” Consider the Movement for Black Lives’ June 4 call to action on community control.

Across Black time and space, there has been a concerted effort to document and preserve the voices of communities in rebellion and the lived experience of oppression and state violence. Universities and local historians have launched large-scale efforts to capture the memories of the survivors and foot soldiers of 1967 Detroit, 1967 Newark, and the lesser-known 1978 Crown Heights — where New York City police ended 30-year-old Arthur Miller’s life with a chokehold like the one that ended Eric Garner’s almost 40 years later.

As researchers of political life, we too have learned the power of listening to our nation’s most surveilled citizens to better understand the confines of democracy, and its potentialities. In our research for the Portals Policing Project, we explored unmediated political discussion of more than 800 conversations between residents of highly policed communities in Baltimore, Chicago, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, and Newark. We did so using a civic infrastructure called “Portals” — gold shipping containers retrofitted with an immersive audiovisual technology that connects people at a distance — to listen to people’s political ideas, practices, and aspirations. Time and again, we heard expressions that desired freedom from police violence and collective autonomy to keep their communities safe. We heard examples of individual and organized efforts to walk the block, police the police, and create alternatives to police surveillance.

After recounting multiple instances of police harassment, a participant in Chicago concludes, “we need to police ourselves. That’s why a lot of these riots happening out here, because people fed up, like, man, I’m tired of them just abusing they authority just ’cause they got that badge and that gun.” Another man in Chicago says to his conversation partner plainly, “I’m for walking in our neighborhoods. I’m not for walking to the police station.” Others went beyond individual efforts and pursued collective solutions that prioritized more restorative forms of community control. A young female organizer and self-described abolitionist in Chicago describes her organization’s focus on community-run health care, nutrition, education, and art — ”things like that restore the justice.”

Despite generations of efforts to capture the narratives of policed communities, community autonomy is the theme most obscured by history. Yet it survives as one of the most consistent political aspirations in segregated Black spaces. Whether the momentum of this moment will be enough to realize this vision remains to be seen.

Gwen Prowse is a doctoral candidate in the departments of political science and African American studies at Yale University and an affiliate of the Justice Collaboratory at Yale Law School. She is the co-PI on the Portals Policing Project.

Vesla M. Weaver is the Bloomberg distinguished professor of political science and sociology at Johns Hopkins University and co-author of Arresting Citizenship: The Democratic Consequences of American Crime Control. She is the co-PI of the Portals Policing Project.

Jack White provided research assistance that went into this article.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Gwen Prowse

Read More