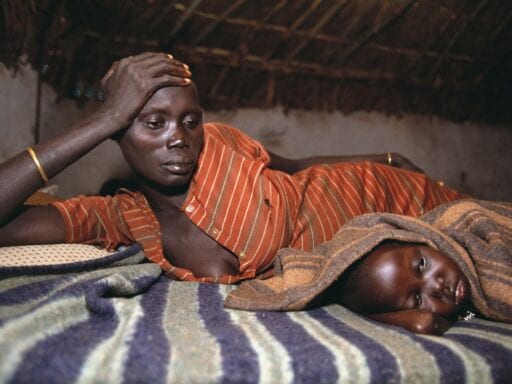

Tens of thousands of women die and hundreds of thousands of babies are stillborn due to malaria. We can do better.

Malaria kills hundreds of thousands of people every year, especially young children. It’s also exceptionally dangerous to another at-risk group: pregnant women.

Researchers have estimated that 10 to 20 percent of maternal mortality in countries where malaria is endemic is malaria-related. That’s almost 30,000 women every year. Pregnancy loss, and long-term disability caused by exposure to malaria in utero, are even more common. And many drugs that are used to save people dying of malaria are not safe to use during pregnancy, or are not widely used even though they are safe.

A new study published in The Lancet: Child and Adolescent Health offers a comprehensive account of just how much this deadly disease affects pregnant women — and suggests that changing treatment options could significantly improve the situation.

Even as we’ve fought to combat malaria deaths overall, we haven’t done as much as we could for pregnant women — and the total toll of malaria is much larger than we might realize, when its effects on pregnancy loss are fully considered.

Malaria’s effects on pregnancy, explained

Malaria is caused by parasites that are transmitted to people from mosquito bites. Last year, there were more than 200 million cases of malaria, and at least 400,000 deaths, mostly among young children. It is still one of the world’s deadliest killers.

The good news is that public health efforts have made a big difference in reducing malaria deaths: Insecticide-treated bednets and seasonal preventative malaria treatment both have a strong, well-supported track record, and have saved hundreds of thousands of lives. Addressing malaria is one of the world’s most cost-effective giving opportunities, and one we’ve often recommended here at Vox.

But the official numbers may underestimate malaria’s toll, because they mostly do not include stillbirths, neonatal deaths from low birth weight, and late-term pregnancy loss. Malaria causes all of these problems, the Lancet study argues.

“[Malaria] infection at delivery is associated with some 200,000 stillbirths per year in sub-Saharan Africa,” the paper says. It adds, “Up to 100,000 infant deaths each year are attributable to low birthweight caused by maternal infection with P falciparum during pregnancy in Africa.”

Malaria during pregnancy is overwhelmingly common in parts of Africa where malaria is endemic: One modeling study estimates that in 2010, 40 percent “of women in malaria endemic areas in Africa in 2010 had placental malaria at some stage during pregnancy.” That’s an astonishingly large number.

And while most people who live in malaria-endemic areas have acquired immunity to malaria by the time they are adults, this immunity doesn’t fully transfer to the fetus. The result is that when women contract malaria while pregnant, they face a significantly elevated risk of miscarriage (which, the paper notes, in low-income countries is often defined as any pregnancy loss before 28 weeks, well past the cutoff to be considered a stillbirth in high-income countries) and an elevated risk of stillbirth or neonatal death due to preterm birth or low birth weight.

The complications of treating pregnant women for malaria

There are a lot of difficulties in delivering good malarial treatments to pregnant women. Many of the infections that cause miscarriages, stillbirths, low birth weight, and premature birth are asymptomatic; it can be hard to persuade people to take medications they don’t notice they need when they don’t feel sick, especially when the medications have substantial side effects. Additionally, most malaria-endemic areas are very low-income and don’t have adequate prenatal care of any kind.

But there is reason to prioritize malaria treatments for pregnant women, despite these complications. Pregnancy loss is devastating, and preventing it is an important public health priority. When babies are born prematurely or with low birth weight, they’re at a much-elevated risk of death and lifelong problems, which can be solved by protecting their mothers from malaria. And we’re learning more about which treatments are effective.

In malaria-affected areas, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends chemoprophylaxis — taking antimalarial drugs while healthy to avoid becoming sick — for pregnant women.

However, the paper argues, the existing recommendations have some problems. First, they aren’t widely adhered to: In many at-risk areas, women don’t have access to the drugs. Second, the drugs might interfere with fetal development if taken in the first trimester, so they don’t provide full coverage throughout pregnancy. Even worse, resistance to the drugs is developing among malaria parasites.

Overall, the paper argues, “Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine is not providing the expected reduction in the risk of malaria infection and the subsequent impact of malaria, despite efforts to improve uptake of this strategy.” In other words, giving pregnant women occasional doses of the standard antimalarial just isn’t getting the job done.

There are other drug regimens that might work better. In particular, the WHO has not historically recommended artemisinin-based combination therapies for women to take throughout pregnancy. (Those are a different, more effective set of antimalarial drugs.) This, the paper argues, is a mistake; at first we didn’t know if those drugs caused any pregnancy complications, but recent research suggests those drugs are safe even in the first trimester and last longer in the body, making it less likely that people will catch malaria during gaps in coverage once the drugs wear off.

Such therapies, the paper argues, “should be recommended for pregnant women in the first trimester without further delay.”

The headline numbers for malaria — hundreds of thousands of children dead every year — are bad enough. It’s sobering to realize that in many ways, those numbers don’t capture the scale of the losses, because they don’t count hundreds of thousands more children who are stillborn or die because of low birth weight or premature birth that is ultimately attributable to malaria.

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world: Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Kelsey Piper

Read More