Behind the easy-to-parody language, the new IPO candidate is a cultural touchstone and a real business.

What type of company is Peloton not?

The cycling company at the center of the latest indoor fitness craze thinks of itself as part of virtually every industry, if you believe its new filing for an initial public offering that it unveiled on Tuesday. It’s the latest example of a company stretching itself every which way in order to gin up excitement from the public market. That’s because most investors don’t want to simply believe in a piece of $2,000-plus hardware — but they’re a lot more open to investing in a broader, easy-to-parody tech vision. And that branding could be a factor in why investors are expected to value Peloton at more than $8 billion.

“On the most basic level, Peloton sells happiness,” founder John Foley explained to investors in his public letter. “But of course, we do so much more.”

To Foley’s credit, Peloton has always been something of a cross between an e-commerce company and a media company. Its business model blends a subscription service with the sale of direct-to-consumer hardware, including in a chain of brick-and-mortar retail showrooms.

But Peloton’s prospectus declares itself to be a full-fledged “innovation” company. It refers to itself as a “technology, media, software, product, experience, fitness, design, retail, apparel, logistics company.”

“Peloton is so much more than a Bike — we believe we have the opportunity to create one of the most innovative global technology platforms of our time,” Foley says. “It is an opportunity to create one of the most important and influential interactive media companies in the world; a media company that changes lives, inspires greatness, and unites people.”

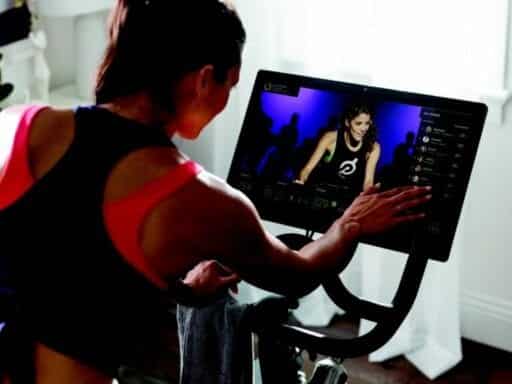

Peloton sells internet-connected bikes and, beginning recently, treadmills that have become a widely recognized, popular brand — almost a cultural touchstone — that allow people to work out without leaving their homes. Founded in 2012, the company also sells recurring subscriptions to live classes that are meant to simulate the experience offered by some of its competitors, like SoulCycle and FlyWheel; these class subscriptions account for about one-fifth of Peloton’s revenue.

And the company does have some attributes of a very promising business, albeit also having enormous marketing costs. Peloton’s revenue has doubled year over year since 2017, reaching $915 million in the year that ended this June. But the company is still not profitable, and it spent $110 million in the most recent fiscal year buying an inventory for its new treadmills, an expenditure that partly led the company to register almost $250 million in net loss in the most recent fiscal year.

Its customer base also appears pretty loyal, as you’d expect. The company claims 1.4 million members and that it only churns through about 0.7 percent of its 500,000 or so subscribers each month.

But whether this is an $8 billion company, which is what its bankers reportedly hope to value it at, depends in part on whether it’s classified as a technology company, a fitness company, or something else. And that’s why Peloton is contorting itself into something bigger as it approaches Wall Street — much like WeWork did earlier this month.

Author: Theodore Schleifer

Read More