Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is a historical drama, sort of. Tarantino has often worked in the historical mode; in films like Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained, he also fantasized about the past. In those movies, he chooses to rewrite history as a kind of act of revenge and righting of wrongs.

Before the film’s Cannes premiere, the director issued a request to those who’d be seeing the film that they not reveal plot spoilers, which — given those known historical predilections — mostly succeeded in sparking murmured speculation about what he was up to. After all, we know Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is at least partly about the grisly, infamous 1969 Charles Manson family murders, which claimed the lives of five people, including director Roman Polanski’s wife, actress Sharon Tate.

And, of course, I’m not going to tell you what happens (not because of Tarantino’s request, but because I’m a professional movie critic). But you don’t need to have any idea of the plot of the film to understand that, if Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained (and, to an extent, even The Hateful Eight) are fantastical, revisionist histories, Tarantino’s latest movie is wish fulfillment on a much grander scale — but simultaneously a more intimate one.

Tarantino, famously obsessed with the history of cinema and its preservation, has recreated a world he wishes he could have worked in with such care and skill and love that, for the most part, it feels like his most personal film. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is lots of fun, but it’s also strangely, hauntingly sad.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood tells a story of a fading world

I should start by confessing that I usually find myself put off by Tarantino’s films. He is clearly one of the most technically competent filmmakers of our time — probably of all time — but his storytelling frequently strikes me as sophomoric and smug, sometimes interested in taunting the audience for their love of violence and sometimes too seemingly pleased with its own cleverness.

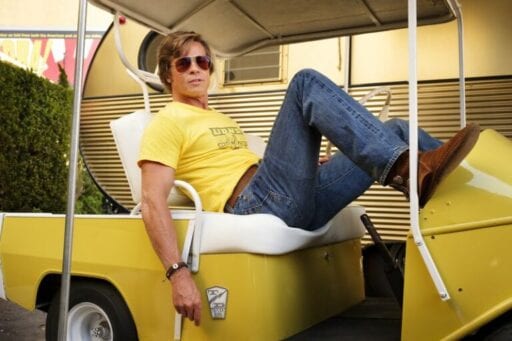

I say all that because it sets up my own reaction to Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. On the whole, I really liked it, possibly more than I’ve liked any of Tarantino’s other films. This is the story of Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), an actor who was huge in the 1950s but whose star is fading. Rick’s stunt double, Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt, who is mesmerizing in this role), also acts as his driver, best friend, and pep talk provider.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16290295/onceuponatime.jpeg) Columbia Pictures

Columbia PicturesBy 1969, Rick, as it turns out, is living next door to the Polanskis on Cielo Drive. He doesn’t know them at all, though he catches sight of Roman (Rafal Zawierucha) and Sharon (Margot Robbie) sometimes as they come up the driveway, living the life he covets.

Two main stories run on parallel tracks in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. One concerns Sharon, who is carefree, innocent, and eager to please. The other follows Rick and Cliff, which often splits into two stories of its own: Rick’s struggle to be an actor of real worth in a changing industry, and Cliff’s brush with a group of teenaged girls (and a few guys) living on an abandoned ranch that once functioned as a movie set. That group, of course, turns out to be the Manson family.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood feels like Tarantino’s attempt to capture a past that could have been

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is a wistful story about the past that’s obviously meant to speak to the present, both eras of a fiercely changing industry. There are nuggets scattered throughout for cinephiles and classic Hollywood aficionados, but also things that recall today’s Hollywood: discussions of various characters’ whispered indiscretions and violent pasts that nobody dares to act on; the small screen threatening to overtake the big screen; young people with different tastes and morals than their elders; cheap knock-offs and factory-line productions imitating earlier, groundbreaking films, that are churned out to make fast bucks. It’s a movie about 2019 as much as 1969.

But on its surface, this is a movie that walks and talks and acts like it’s 1969, and it’s obvious that Tarantino simply loves that time in cinema. There’s a glow over the whole film that feels partly like it’s just California and partly like it’s a retrofitted Golden Age made literal. Part of what makes the director so interesting — and so beloved at history-obsessed film festivals like Cannes — is that he’s possibly the most skilled contemporary wielder of cinematic pastiche: He borrows images, sounds, techniques, and music from different eras but always manages to make them his own.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16290297/onceuponatime2.jpeg) Columbia Pictures

Columbia PicturesThat’s clear right down to the way he shoots his two main leads, Pitt and DiCaprio, who feel almost Redford- and Newman-esque in the way they swagger and talk and flash a grin. It’s also strangely clear (by design or not, I can’t say for sure) in the fact that Robbie, despite being third billed in the film’s credits (behind Pitt and DiCaprio and ahead of a lengthy list of other stars), doesn’t have a lot to say or do in the film.

Tarantino received some heat at the Cannes Film Festival for his (unnecessarily combative) response to a journalist’s question at a press conference, in which he vehemently told a New York Times reporter who asked about Robbie’s relatively small number of lines in the film that he “rejected [her] hypothesis.” But as the actress herself said in her response, her character has some of the film’s most moving scenes. Sharon Tate is often remembered as little more than the actress from Valley of the Dolls, the wife of Roman Polanski, and the girl who got murdered by the Manson family. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood gives her emotional depth.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16290301/onceuponatime4.jpeg) Columbia Pictures

Columbia PicturesI can’t quite explain this part without giving anything away, so you’ll just have to trust me: The way Once Upon a Time in Hollywood unwinds its story makes it clear that it’s more of a lament — a requiem for a past age, one that he deeply wishes didn’t have to pass away.

Tarantino is not alone in this. Joan Didion, who was an acquaintance of Tate’s, wrote in her famous essay “The White Album” of the murders on Cielo Drive as the marker for many people of the end of the ’60s. It was the moment when “the tension broke,” she writes, but it’s also one of the most significant events of the summer of 1969, one that made her feel as though the world had quit making sense and was going to pieces.

Popular culture has continued to try to make sense of the event, which takes on mythic proportions. Movies from 1976’s Helter Skelter to 2015’s Manson Family Vacation and TV shows like NBC’s Aquarius and FX’s American Horror Story: Cult have replayed the story and its cultural legacy, either literally or as a template for stories about cults and killings. Hollywood historian Karina Longworth’s excellent podcast You Must Remember This devoted an entire season to Manson’s Hollywood. In 2016, Emma Cline’s novel The Girls fictionalized the events in an attempt to look inside the Manson girls’ psychology. Two movies have already come out in 2019 about Manson and the murders: Charlie Says and The Haunting of Sharon Tate.

But for Tarantino, the murders aren’t the main interest. He’s most fascinated by the world around them, in the fact that Manson ultimately wound up in Hollywood and not some other place. The factors that might drive girls to follow a man like Manson might also be linked to what caused Rick Dalton’s star to start fading.

Tarantino is nostalgic for that time, and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is more his tribute than an unpacking or analysis of what it all means (unlike, for instance, the Coen brothers’ 2016 film Hail, Caesar!, which has something to say about warring ideologies in the industry at the same time).

By the end of the film, Tarantino falls back into some of his familiar tropes. It’s as though he just can’t stop himself from dipping into old habits but doesn’t really know why and isn’t sure how to stick the landing. But until that point, it is a star-studded joy to watch. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood doesn’t have a lot to say, in the end. And yet it manages to capture some of that old-time Hollywood movie magic.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May. It opens in US theaters on July 26.

Author: Alissa Wilkinson

Read More