Experts warn prisons and jails aren’t ready for a pandemic — and that could hurt everyone else too.

The next site of a deadly coronavirus outbreak may not be a cruise ship, conference, or school. It could be one of America’s thousands of jails or prisons.

Just about all the concerns about coronavirus’s spread in packed social settings apply as much, if not more, to correctional settings. In a prison, multiple people can be placed in one cell. Hallways and gathering places are often small and tight (often deliberately so, to make it easier to control inmates). There is literally no escape, with little to no space for social distancing or similar recommendations experts make to combat coronavirus. Hand sanitizer can be contraband.

Such an outbreak could not only infect and kill hundreds or thousands of people in prison, but potentially spread to nearby communities as well. Visitors and correctional staff could spread the disease when they go back home, and inmates could spread it when they’re released.

Even an outbreak contained within a jail or prison could strain nearby health care systems, as hundreds or thousands of people suddenly need medical care that jails and prisons themselves can’t provide.

So if you want to “flatten the curve” to spread out the illness and avoid overwhelming health care systems, experts say, you should worry about coronavirus in prisons and jails.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19780273/flattening_the_curve_final.jpg) Christina Animashaun/Vox

Christina Animashaun/VoxIn the US, the concern is particularly acute because America puts so many people in jail or prison. The US locks up about 2.3 million people on any given day — the highest prison and jail population of any country in the world. With an incarceration rate of 655 per 100,000 people, the US locks up people at nearly twice the rate of Russia, more than five times that of China, more than six times Canada and France, nearly nine times Germany, and almost 17 times Japan.

“We can learn what works in terms of mitigation from other countries who have seen spikes in coronavirus already, but none of those countries have the level of incarceration that we have in the United States,” Tyler Winkelman, a doctor and researcher at the University of Minnesota focused on health care and criminal justice, told me.

It’s also a situation that’s particularly new to the US. Since it dramatically ramped up its incarceration rates in the 1970s and ’80s, the country hasn’t faced an outbreak like Covid-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus. The closest point of comparison might be a bad flu season or the HIV/AIDS epidemic, but neither is closely comparable to a new virus that’s deadlier and more contagious than the common flu and can spread through limited contact.

Jails and prisons still have time to prepare. They could release inmates, even temporarily, who don’t absolutely need to be there. They could try to make handwashing and otherwise good hygiene easier for inmates and prison staff. They should prepare to cancel activities, programming, or visits as an outbreak nears, replacing them with video conferences and phone calls when possible.

But as coronavirus spreads, the window to prepare is closing.

“I’m incredibly worried,” Wanda Bertram, a communications strategist for the Prison Policy Initiative, told me. “It really is a matter of time before a prison or jail starts to suffer serious consequences of having a lot of people packed together, supervised by people that view them as a serious threat rather than a population to be cared for.”

She added, “I don’t have a lot of faith that they’re going to do the right thing.”

Mass incarceration makes the coronavirus risk worse

A lot of countries are going to face new challenges in their jails and prisons due to the coronavirus pandemic. But the US is unique, because mass incarceration has led to millions of people incarcerated across thousands of jails, prisons, and other correctional facilities in America — any of which could become hotbeds for disease on their own.

It’s not just the number of people in jail and prison, but the number going in and out of them. As criminal justice expert John Pfaff pointed out, roughly 5 million people go in and out of jails alone each year. There are also visitors and correctional staff, who interact — sometimes in very limited spaces — with inmates. Any of these people can bring the virus in and take it out.

No other country faces a risk quite like this. Even the states that incarcerate the least numbers of people in the US still lock up far more people than the vast majority of other countries: The Prison Policy Initiative in 2018 estimated that the incarceration rate of Massachusetts, the least carceral state, was more than double that of England and Wales and nearly triple that of South Korea.

So a prison outbreak would present a potentially deadly risk to a relatively massive population, which, on top of everything else, disproportionately suffers from chronic illnesses and other health conditions that could exacerbate Covid-19.

Jails and prisons also present an elevated risk for other types of facilities and institutions. Winkelman, who works in the Hennepin County jail and local homeless shelters, noted that there is a lot of overlap between jailed and homeless populations. Someone released from a jail, then, could infect people in a homeless shelter, or vice versa, causing an outbreak that could bounce back and forth between both places, infecting far more people than would be in a jail or homeless shelter alone.

But even if an outbreak is contained to a jail or prison, the effects could spill over outside.

“All of these mitigation strategies — of closing schools, stopping conferences, decreasing travel — are to slow the speed at which people get the virus so that we don’t overwhelm our health care system,” Winkelman said. “If Covid spreads in a large, thousand-person facility, and within five days you have a thousand people with multiple chronic conditions who just got the virus, that has the potential to really overwhelm a health care system.”

One problem is that jails and prisons notoriously do a bad job providing health care to inmates. As a CNN investigation last year revealed, these facilities often deny or delay even basic medical care, causing preventable complications and deaths. In the context of Covid-19, those kinds of delays could mean more time for a sick inmate to infect others.

This is in part by design: To get to prison doctors and nurses, inmates usually have to go through guards who often have different priorities.

“The system of care that exists around any given person, whether they’re incarcerated or not, is not just doctors or nurses, but it’s also the people who are in their immediate vicinity and taking care of them on a day-to-day basis,” Bertram said. “That’s why it really matters when those people are family members as opposed to when those people are correctional staff, who think of you as a threat.”

People in jail or prison also have less access to things we might take for granted in the free world that help prevent the spread of infection.

“If you spend even just a couple of minutes in any jail or prison area, you would quickly find that many of the sinks there for handwashing don’t work, or that there are no paper towels or no soap,” Homer Venters, former chief medical officer for New York City Correctional Health Services, told the Brennan Center, a criminal justice reform group. “In other words, handwashing, the most basic tool that incarcerated people have, won’t be consistently available. Jail and prison administrators should be thinking right now about how they can put more infection control measures into place very quickly.”

Jails and prisons should prepare while they can

Some jails and prisons are already taking some steps to prevent the spread of coronavirus, particularly banning visits.

But most jails and prisons still aren’t fully prepared, Winkelman said. “No jail or prison in the world has ever seen anything like this. There are policies in place to handle influenza, but we don’t have, historically, policies around what to do if prisons and jails can’t slow down the spread of a virus in a correctional facility.”

So what can they do? Winkelman pointed to recent guidance by the Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs, which he called the best he’s seen so far. The guidance is especially relevant for Washington state, which has the second-highest number of reported Covid-19 cases in the US after New York state.

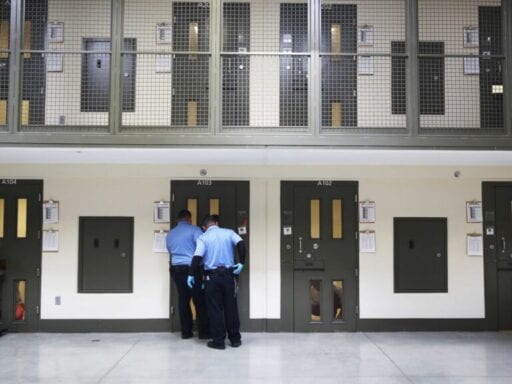

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19812012/GettyImages_1188739505.jpg) Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Spencer Platt/Getty ImagesOne recommendation: release some inmates. “Are there people you can release on their own recognizance? Do you have a priority list (who do you release if you need to downsize by 5%? 10%? etc.)?” the guidance asked. “Are there alternatives to arrest for certain crimes, or, in dire situations, are there crimes for which your patrol division will not arrest?” Another possibility is a furlough, in which some inmates are released temporarily, particularly those who are older and have health conditions that could make Covid-19 more dangerous.

This isn’t unheard of. Iran, for example, drew headlines for temporarily releasing 70,000 inmates as it deals with one of the world’s worst outbreaks, with the third-highest number of confirmed coronavirus cases, after China and Italy. And local criminal justice officials in San Francisco are pushing for similar action there.

The goal, however, should be to release inmates before an outbreak gets bad. Once an outbreak begins, after all, releasing inmates could spread the disease outside, especially since coronavirus can spread even if someone doesn’t have symptoms.

Another possibility is for jails and prisons to try social distancing where they can. For visitations, jails and prisons could host meetings in non-contact rooms, or move visits to video or phone calls in the meantime. In other areas, they could push staff to stay home when they’re sick (including by providing paid sick leave), work from home if possible, and temporarily curtail or cut activities or programming for inmates.

Prisons and jails could also make self-care like hand washing and cleaning easier, and make medical services more accessible. Initially screening and testing inmates, and subsequently isolating them and those they may have come in contact with if they test positive, is crucial to stop the spread of Covid-19 in jails and prisons, just like it is in the outside world.

At the same time, it’s important for jails and prisons to not get too carried away, including with inmates who prove to be sick.

“Inmates in isolation should have ample access to comfort, entertainment, and activity-related materials allowed by their custody level,” the guidance from the Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs explained. “An important reason for this suggestion is that you want to do everything possible to encourage inmates to notify medical staff as early as possible if they experience symptoms of infection. Fear of being placed in an overly-restrictive cell may delay their notification, which is counterproductive.”

Above all, though, jails and prisons should take coronavirus as a serious threat — not just to themselves, but the greater public too — and work with public health officials accordingly.

“It’s an exaggerated version of what we talk about all the time when we talk about the public health impact of mass incarceration — when we say that this is not just something that puts incarcerated people in danger but something that puts whole communities in danger,” Bertram argued. “You’re creating hotbeds of illness, and you’re creating damage that’s eventually going to have to be borne by these people and their families once they’re released. So it’s really a concern for everyone.”

Author: German Lopez

Read More