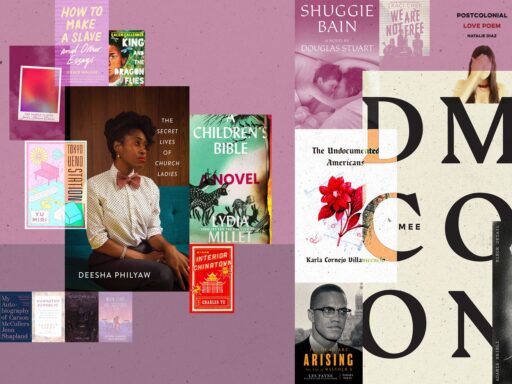

From Black church ladies to undocumented immigrants, here’s what this year’s shortlist looked like.

Every year, the National Book Foundation nominates 25 books — five fiction, five nonfiction, five poetry, five translated, five young adult — for the National Book Award, which celebrates the best of American literature. And every year (well, every year since 2014), we here at Vox read them all to help people figure out which ones they might be interested in. Here are our thoughts on the class of 2020. The winners will be announced at a virtual ceremony on November 18.

Fiction

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22045523/LeaveWorldBehind_cover.jpg) Ecco

EccoLeave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam

It likely seems deeply unappealing, in this time of big but formless crises, to read a book about … a big but formless crisis. It probably seems even more unlikely that Rumaan Alam’s third novel — which follows a vacationing family as they grapple with said disaster, which is never named but which causes power outages, mass death, and general havoc across the nation — is fun.

Against those odds, however, I couldn’t have asked for a better read in the week before the US presidential election, held against the backdrop of a worsening pandemic. Alam’s writing is sly and elegant, studded with so many urban-middle-class Easter eggs that at one point I photographed a description of a grocery list that could have served as my own the last time I went upstate for a long weekend. (It’s also cinematic to the point that I dream-cast a limited-run TV series mid-read.)

Even if you are unmoved by Martin’s potato rolls and vodka cocktails, the book presents a near-universal set of questions that feel eerily prescient given that Alam likely did not write Leave the World Behind within the last several months of the pandemic: How should we respond when faced with a threat we can’t name? How do class and race figure in, and where does the promise afforded by money run out? And what mundane, foolish, or downright ugly thoughts will occupy us even when we know the stakes are much higher than they’ve ever been? I, for one, am making a beeline for the vodka.

—Alanna Okun, deputy editor for The Goods

A Children’s Bible by Lydia Millet

A Children’s Bible is so intricate, and so bleedingly of-the-moment, that it’s hard to believe it wasn’t written last month. It braids allegory and realism, post-apocalypticism and fable, in a way that kept setting off little explosions in my brain.

It’s a slim novel, just 224 pages, but the story it tells is epic. It’s narrated by a child who is on vacation with her parents and younger brother Jack. They’re at the beach in a big rented house with the families of their parents’ college friends. All of the adults drink continuously and without ceasing. The children are left to their own games.

Then the big flood comes, and everything changes. Part of A Children’s Bible is a slow, sly retelling of the most disturbing and apocalyptic stories in the Bible, from the flood of Noah to the birth of a child in a stable. But it’s not too literalist; it’s also about environmental collapse and the struggle of the young to fill the gaps that older generations were too distracted by profit and pleasure to address. And it has the rhythms and cadences of an extended legend spun for a new age, in which science holds as much allure and mystery as religion once did. It is brilliant, unnerving, and worth every moment.

—Alissa Wilkinson, film critic

The Secret Lives of Church Ladies by Deesha Philyaw

One of the reasons we cover the National Book Awards at Vox in ways we don’t cover other literary prizes is that every year, the National Book Awards recognize books like The Secret Lives of Church Ladies — books that don’t make the shortlist at other august literary institutions.

Books like Secret Lives don’t get overlooked because of their quality; Deesha Philyaw is the kind of author who writes vivid, inescapable voices, and you can hear her characters whisper in your ear as you read. They get overlooked because of marketing categories. A short story collection about Southern Black women from a debut author, published by a small university press? Not in these Pulitzers.

But The Secret Lives of Church Ladies is worth your time. It’s about the relationship between faith and self-expression, told in a series of opposing character binaries. Nearly every story features one Black woman committed to the church to the point of self-censorship, and another struggling to carve out her own identity in the space between herself and the church. In “Eula,” it’s two women who tryst together every New Year’s Eve; only one of them considers herself a committed virgin saving herself for her future husband. In “Peach Cobbler,” a girl watches her mother carry on an affair with her pastor; only the little girl believes the pastor to be God. These are vivid, vibrant stories that will linger on your tongue like sweet tea.

—Constance Grady, book critic

Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart

Reading Douglas Stuart’s grainy, gritty Shuggie Bain is a formidable experience. Stuart tells the story of growing up in 1980s Glasgow — the poverty, the drinking, the industrial grit, the pain — through the eyes of Shug, a boy who can’t yet put into words why he’s different from the other boys his age. But his enigmatic mother, Agnes, figures it out when his parents find him playing with dolls.

Agnes has her own problem, which becomes clearer and clearer to Shug: addiction. And it’s the relationship between these two, when each one is the only one the other has left, that Stuart explores.

The result is a brutal story both in plot and in the language Stuart uses (“the way they fidgeted, he could tell that the people had waited a long weekend for their benefit books to be cashed”). And, in spite of its emotional jaggedness and the raw pain that Shug witnesses, it strives to find how love still persists. Shuggie Bain certainly does not resemble the kind of unconditional love stories we’re taught to idealize. Nor is it ever in danger of falling into the trope that love is powerful enough to conquer all. But despite all the brutality and awfulness of this world, love still survives. And that survival feels, in its own way, like some kind of hopeful thing.

—Alex Abad-Santos, senior culture correspondent

Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu

Charles Yu’s first novel, How to Live Safely in a Science Fiction Universe, was a dizzying spiral through genre tropes, all in service of a heartfelt story about relationships between fathers and sons. That novel’s protagonist was named Charles Yu, and it almost read like a memoir that somehow involved time travel. The space between reality and unreality is where Yu thrives.

Interior Chinatown, his second novel, amplifies earlier themes. (Yu has also published two short story collections.) Written partially in screenplay format — with dialogue centered beneath the all-caps names of the person who’s speaking — the book is about a man named Willis Wu, an actor who longs to climb through the ranks of “types” he’s allowed to play as an Asian man, so that he might attain the coveted title of “Kung Fu Guy.” Willis lives in a tiny apartment above the Golden Palace restaurant, where Black and White, the TV show he plays bit parts in, perpetually films.

If all of this sounds like something out of the surreal short stories of Kelly Link or Carmen Maria Machado, you’re not far off. And it takes a second for Interior Chinatown to make sense as a novel, rather than a treatment for a movie. But the screenplay structure is intentional. The way that Yu sets up his dramatis personae in exacting yet unspecific detail apes the ways Hollywood itself creates only the most stereotypical roles for actors of Asian descent to play. And the deeper you get into Interior Chinatown, the more playful it becomes, as Yu drops his protagonist into all manner of other TV genres (including a kid’s show!) while staying true to Willis’s emotional journey. (Yu’s experience writing for television on shows like Westworld and Legion shines through.)

The novel culminates in an ending straight out of a feel-good Hollywood feature film that, nevertheless, calls attention to all the straitjackets American society places Asian Americans in. It’s a canny piece of writing, at once incredibly clever and sneakily moving.

—Emily VanDerWerff, critic-at-large

Nonfiction

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22045528/Undocumented_Americans_by_Karla_Cornejo_Villavicencio.jpg) One World

One WorldThe Undocumented Americans by Karla Cornejo Villavicencio

In an era when the conversation around US immigration policy has been dictated by the Trump administration’s extreme abuses — from family separations to forced hysterectomies performed on detained immigrants — The Undocumented Americans is a personal portrait of the more than 10 million people living in the shadows and the quotidian horrors they face.

Karla Cornejo Villavicencio, a Harvard graduate who came to the US from Ecuador as a child, is one of the exceptional undocumented immigrants who was shielded from deportation under DACA — the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. But she does not aim to inspire. She actively avoids the trope of the “model immigrant,” acknowledging her complicated relationship to success, as a product of the pressure many immigrant children face to provide for their parents in the absence of a social safety net.

Instead, she turns her lens on decidedly ordinary undocumented people for whom the American dream has proved a fallacy: day laborers in Staten Island; residents of Flint, Michigan, drinking poisoned water; and women in Miami who have turned to natural remedies in the absence of affordable health care, among others. She realizes them with all of their idiosyncrasies in stunning, sometimes larger-than-life prose, writing not with the clinical eye of a journalist, but with the devotion of someone who shares a common history with her subjects.

She admits that she burned all the notes from her interviews, and for that reason, her book is not quite nonfiction. But her rendering of her own community is truer than any direct transcription.

—Nicole Narea, immigration reporter

The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X by Les Payne and Tamara Payne

Malcolm X is a familiar figure to most Americans. His story appears in grade school textbooks, and in the lyrical account of his life he wrote with journalist Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

But The Dead Are Arising posits that we don’t know the civil rights hero as well as we might think.

Methodically — and drawing on interviews conducted with his friends, family, and associates over a nearly 30-year period — authors Les and Tamara Payne pick apart the mythic Malcolm X created in his autobiography.

They depict him less as a larger-than-life legend, and more as a singularly driven man animated by a unique upbringing — shaped by time, place, and circumstance. The clever criminal of X’s early years is replaced by a cruel, competitive creature possessed of a deeply selfish arrogance, and the proselytizing “shining Black prince” of his later years is supplanted by a frustrated would-be civil rights leader who routinely suppressed his better judgment to court the praise of a hypocritical surrogate father.

The Paynes’ work — which Les did not live to see in print — lacks the vividness and immediacy of X’s autobiography, and is perhaps best read as a companion to that work rather than a standalone volume. The authors appear to assume their reader has at least a passing familiarity with The Autobiography, and at times seem more interested in filling holes in that narrative than in telling X’s story itself.

Some of those holes aren’t very interesting — X and Haley, it is revealed, created some composite characters — but others are deeply fascinating.

The authors report in detail a secret meeting X had with the Ku Klux Klan, one he was compelled to take by his mentor, Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad. They explain how that meeting — as well as the Nation’s subsequent secret partnerships with white nationalist groups — helped precipitate X’s split with the religious order he had a hand in building. Also of note is the way the Paynes illuminate how those alliances ultimately contributed to X’s assassination by Nation of Islam gunmen.

They unravel outstanding questions about the killing, while casting new light on X’s post-Nation of Islam activism, including his work in fusing African liberation movements with America’s civil rights battles.

Rich in reporting, and full of the voices of those who knew Malcolm X best, the Paynes’ book ultimately delivers on its title. The authors provide the details of the revolutionary’s life and manner of thinking in minute detail. In reading their work, it does feel as if the dead are reappearing, and as if they have a lot to say.

—Sean Collins, politics and policy associate editor

Unworthy Republic: The Dispossession of Native Americans and the Road to Indian Territory by Claudio Saunt

The legacy of Native American resettlement across the US continues to play a role in national politics today — whether it’s Native voters in Arizona narrowly swinging their state for Joe Biden or the ongoing battle to decide what land actually belongs to Native Americans, let alone who has sovereignty over it.

Claudio Saunt’s Unworthy Republic tackles a specific aspect of this history: the intense period of resettlement, which he more accurately labels “forced expulsion,” that took place during the 1830s under Andrew Jackson. The most valuable aspect of Unworthy Republic is that it situates its look at this state-sponsored mass deportation within the context of other state-sponsored mass deportations throughout history.

Saunt isn’t overbearing on this devastating point. He simply states upfront that America’s period of forced expulsion was a major geopolitical turning point in world history, one that paved the way for others to follow. And then, with incredibly straightforward language, he frames his observations of the past in ways that perpetually return readers to the present. For example, here’s Saunt summing up one of his subjects in a way that feels almost like Trumpian satire: “The counterpart to McCoy’s contempt for easterners was a stubborn insistence that he knew best, despite his exposure to only a small fraction of the diverse indigenous peoples living within the boundaries of the United States and its territories.”

Unworthy Republic is a book about resettlement — but it’s really about lasting consequences and the ongoing conflict between humanitarianism and opportunistic colonization; as uncomfortable as its truths are, it’s an unforgettable read.

—Aja Romano, culture writer

My Autobiography of Carson McCullers by Jenn Shapland

It didn’t take long for Jenn Shapland to convince me, at least, of what might be considered the central thesis of her nonfiction debut, My Autobiography of Carson McCullers — namely that the iconic American author of the title passionately loved a number of women, including her therapist, and, although she never described herself as such, was likely a lesbian. McCullers’s hidden-in-plain-sight loves, which Shapland researches through archival material — letters and photographs and clothes and even transcripts of her therapy sessions — are rendered achingly through both Shapland’s words and McCullers’s own.

With that history seemingly unearthed, what follows is a beautiful consideration of the nature of proof, and of self and identity and queerness and history and progress. As Shapland bounces between literary locales (libraries, archives, McCullers’s home in Georgia, her own home of Santa Fe, the New York artists community Yaddo), she touches on many pieces of the past that we’d like to rename with the benefits of insight and hindsight, on the limits of that insight and hindsight, and on the deep human need to recognize and honor love.

“If this isn’t love I don’t know what is,” Shapland writes, “Or care.”

—Meredith Haggerty, deputy editor for The Goods

How to Make a Slave and Other Essays by Jerald Walker

How to Make a Slave and Other Essays is didactic, but not in the traditional sense. Jerald Walker hasn’t set out to help us understand moments in Black history — he instructs readers on how to live with Black history, a history that’s harrowing and marked by the constant search for liberation.

From the outset, Walker tells us that it’s imperative to “find a funny part” in Black history, or at least to wish there were some funny parts. Finding something funny in the hefty weight of it all can help us get on with it, Walker posits — though he makes it abundantly clear that the color of his skin is typically top of mind for Black men like him. Whether it’s making a decision about whom to date, whom to marry, where to live, or how to raise kids, Walker’s Blackness can’t be denied.

Through the many experiences that Walker recounts, from learning how to parent or write to riding Amtrak to finding joy, as a child, in Michael Jackson, Walker proves that Black life doesn’t have to be about victimhood or about pervasive misery, pain, or fear, and that the full Black experience deserves to be told. Black stories don’t have to be about stereotypical ideas of what Black people battle; instead, they should celebrate the courage and strength they consistently summon. At a time when Black identity is being examined in the context of a national reckoning on race, Walker shows Black people how to find comfort and direction in who they are.

—Fabiola Cineas, identities reporter

Poetry

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22045531/treatise_on_stars_cover.jpg) New Directions Publishing Corporation

New Directions Publishing CorporationA Treatise on Stars by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge

I have never been a poetry person. It’s always felt inaccessible to me — too obtuse, too above-my-head. Just words! That I often couldn’t understand!

Then 2020 happened. No words made sense. It was hard to read, hard to think. All I wanted was to be soothed. So I gave poetry another try.

Turns out poems are indeed comforting, not to mention short. It’s also fine if you don’t fully understand them. Sometimes, the language itself, the mood it creates, is the point. This is certainly true of Mei-mei Berssenbrugge’s lyrical body of work, including her most recent collection, A Treatise on Stars.

It doesn’t matter that the lingual abstractions Berssenbrugge draws about space, who might inhabit it, and how we all relate to each other, can be difficult to parse. During a period marked by darkness, distress, and isolation, there is escape in reading work concerned with what we lack: light, wonder, connection. You don’t have to entirely grasp what is being said to feel what’s being evoked.

—Julia Rubin, editorial director for culture and features

Fantasia for the Man in Blue by Tommye Blount

It’s maybe weird to say this about poetry that deals with police brutality, but Tommye Blount’s marvelous collection, Fantasia for the Man in Blue, teems with desire. Blount’s desire is self-aware and dizzying and thrilling and omnipresent: desire for the cold, soulless traffic cop whose late-night traffic stop is both terrifying and titillating, and who becomes the title figure Blount returns to throughout his four-part poetry arc; desire for the famed drag queens he idolizes like Latrice and Lady Chablis; for the men he’s known and loved only for frantic one-night stands.

But it also teems with images of violence, almost subconscious, repetitive, and impossible to dispel — tiny and giant outbursts of violence like shrapnel, from knives to shattered glass and dishes to birds battered against windshields. Desire and violence become inextricable in the whirling, frenetic rhythm of Blount’s poetry, until you understand that their constant tussle is a kind of erotic dance of survival in Blount’s mind — the dance that Blount, as a queer Black man, loathes and celebrates. At times, this dance itself is horrifying, like when Blount tries to mentally reframe a dangerous gang assault as an illicit orgy; at other times it falls away to make room for something even more chilling, like when the orgy gives way to an image of Matthew Shepard’s killer lovingly cleaning his gun. Fantasia for the Man in Blue traps you inside its whirlwind of conflicting human emotions; “knife me into what fathers hunger,” Blount writes. It’s messy and loving and dark, and inescapably human.

—Aja Romano

DMZ Colony by Don Mee Choi

“I won’t say what they did to me … I’ll leave it up to your imagination …”

This is the end of DMZ Colony’s first ellipsis-filled transcript from Ahn Hak-sop, who was held as a political prisoner in South Korea from 1953 to 1995. His captivity, he tells poet Don Mee Choi, stemmed from aiding North Korean forces as Soviet- and American-backed regimes began their long battle. Despite Ahn’s call for ambiguity, the ellipses the poet adds to this account do not attempt to hide the horror of Ahn’s matter-of-fact mentions of torture.

We know it is coming, and our knowing makes us complicit.

Choi’s DMZ Colony is not really a collection of transcripts. It is a memoir in fragments, of the poet and of a nation. It opens with a picture of birds in formation, their morphing lines perhaps resembling the vagaries of a map.

What can poetry communicate, and what can prose? Choi suggests that the division of a country cannot be explained in one or the other, or simply in words. As stories from Ahn and imagined others continue, they are arranged into lines of poetry, alongside images of scribbles from Choi’s notebook.

Choi is a translator. She makes transparent her process of converting personal narrative into history and back, inviting the reader to interpret with her.

then I heard the vowels from my own mouth

O E

A E

I E

E E E

이 이 이

“The language of capture, torture, and massacre is difficult to decipher. It’s practically a foreign language,” she writes.

That is how we slept

like spoons

like bean sprouts […]Operators of spoons

bean sprouts

beat, beat, beat

then everyone came

then terror

then korea

Translation is not impossible. The hardest part comes next.

—Tim Williams, copy editor

Borderland Apocrypha by Anthony Cody

Anthony Cody’s debut collection is screaming experimental poetry. Channeling other great documentary poetry works like Muriel Rukeyser’s Book of the Dead, Cody looks at the lynching of Mexican Americans following the Mexican-American War. He does this through direct historical quotations and feats of linguistic explosion; he flits between English and Spanish, breaks poems into sentence diagrams, removes all the vowels altogether (“ll th sft lttrs hv blwn ff”), and tries to extrapolate American violence into a kind of semantic form so that its impact on the body, on the spirit, on generations of immigrants, can be dismantled and grappled with, then hopefully transformed into something new and hope-filled.

But this process of transforming trauma into something survivable and conquerable is industry. It’s cyclical, it’s exhausting; as Cody writes at one point, “The inheritance of the elsewhere is a cave of collapse. … The cave of collapse is work.” We feel this weary labor throughout Borderland Apocrypha — for instance, when Cody incorporates into one poem actual Trip Advisor reviews of a Texas hanging tree where Mexican civilians were lynched in a wave of violence that left 70 people dead. “The tree has quite the history,” one reviewer says. “AskThemIfTheyNoticeYourShadow’sShapeIsAMassBurialofTwitchingLegs,” Cody writes. This is not easy poetry, nor is it supposed to be.

—Aja Romano

Postcolonial Love Poem by Natalie Diaz

In a stunning collection, Native American poet Natalie Diaz highlights an aspect of colonization that’s rarely confronted: what’s taken.

“An American way of forgetting Natives: Discover them with City. Crumble them by City,” she writes in one poem titled “exhibits from The American Water Museum.” “Erase them into Cities named for their bones, until you are the new Natives of your new cities.” In another poem, the title alone — “Manhattan Is a Lenape Word” — underscores this point.

Throughout the book, which is interspersed with lush verses addressed to a lover, Diaz emphasizes how the US has brutalized, racially profiled, and mythologized Native Americans. The country’s identity, she notes, is inextricably tied to these acts, and to a failure to reckon with them.

“I carry a river, it is who I am,” Diaz writes while citing a Mojave phrase. Clearly and devastatingly, she underscores how the US will forever carry the refusal to acknowledge its own culpability.

—Li Zhou, politics and policy reporter

Translated Literature

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22045532/HIGH_AS_THE_WATERS_RISE_cvr_300dpi_print_res_copy.jpg) Catapult

CatapultHigh as the Waters Rise by Anja Kampmann, translated by Anne Posten

High as the Waters Rise is the bleak and often emotionless story of Waclaw, a German oil rig worker in his early 50s. Waclaw is reeling from the sudden and intimate loss of his companion, Mátyás, abruptly swept away during a brutal Atlantic storm that consumes the rig. Undone by loss and too afraid to face the specters of his dreams, Waclaw returns to shore and begins a wandering, sleepless odyssey through the countries he’s collected over the decades, visiting cities and people he either cannot or will not bear any true attachment to.

The journey often veers nihilistic, as Waclaw painfully remembers the life he had before abandoning his job as an elementary school janitor to work for weeks at a time far from home. Now, with nothing from his past or present to moor him, we find a character who no longer belongs to the land or the sea. He has only his profound grief for what he’s lost and what he left behind.

The book is a grim representation of working-class characters, told through the lens of a man of few words both inside and out. And the author, who juxtaposes an intensely poetic writing style with her main character’s unyieldingly austere inner monologue, drives home the inescapable inevitability of loss and the relentless indifference of time.

—Ashley Sather, video production manager

The Family Clause by Jonas Hassen Khemiri, translated by Alice Menzies

Just as Elena Ferrante’s novels are about “daughters and mothers,” Swedish author Jonas Hassen Khemiri’s The Family Clause is about fathers and their children. This novel is a tragicomedy that takes place over 10 days: the amount of time a narcissistic and hypochondriac grandfather is staying in Stockholm, where two of his children live. He makes this visit twice a year — not to spend time with family but to avoid taxes and maintain his Swedish residency.

The Family Clause often retells events, but from the perspective of a different character, at times venturing into experimental territory. Like when Khemiri writes from the perspective of the grandfather’s overly confident 4-year-old granddaughter, or from the perspective of the ghost of the grandfather’s deceased daughter, who died tragically.

The story is a brief window of time for the members of this family (whose names we never learn), each at an inflection point. The grandfather’s anxiety-riddled accountant son is on a year-long paternity leave (must be nice, Scandinavia!) and wants to sever an agreement with his father over his tax-avoidance scheme, while also considering a career change to standup comedy. His girlfriend, a union lawyer, is questioning whether their relationship will survive that vocational upheaval. And his sister, the grandfather’s living daughter, is desperate for a reunion with an estranged son while deciding whether to carry a pregnancy to term.

All of the characters are grappling with the legacy of parenting — either the way they were parented or the parents they are trying to be. The characters aren’t quite likable, but they are made vividly real and relatable by the detailed interiority of Khemiri’s prose and the novel’s perspective-shifting format.

—Laura Bult, video producer

Tokyo Ueno Station by Yu Miri, translated by Morgan Giles

Tokyo Ueno Station’s dainty, primary-colored book jacket cuts to the chase: “Kazu is dead.” This does not preclude Kazu from narrating what amounts to a slim, sometimes prosaic reverie. Before his death, Kazu’s life was one of regrets: It was “nothing like a story in a book,” he muses, very meta, at the book’s opening. “There may be words, and the pages may be numbered, but there is no plot. There may be an ending, but there is no end.”

This foretells the structure of Tokyo Ueno Station itself, a book that crawls forward as if weighed down by Kazu’s depression. As a ghost whose body is doomed to haunt the homeless camps around a popular subway station in Tokyo, Kazu recalls what led him away from his family and to this place. Kazu is a storyteller with little consideration for his audience, however; this closed-off dead man is emotionally distant, and that often makes for less pleasurable reading.

As such, it is sometimes hard to follow his story — if not hard to bear. Kazu’s life is interminably sad, filled with abandonment and premature death and suffering. He darts between these moments as if struggling to confront them for himself; it may be easier to muse upon a fellow homeless man’s cat instead of continuing to recount his young son’s death. These situations are all difficult, and Tokyo Ueno Station comes at them not with a present eye but a resigned, faraway one. To reach the end of Kazu’s tale is to learn and embrace, just as he does, that life does not always have a proper end. And maybe we don’t always get the chance to come to terms with that, either, no matter the efforts we make.

—Allegra Frank, deputy culture editor

The Bitch by Pilar Quintana, translated by Lisa Dillman

Sardonic and pitch-black, The Bitch begins when childless Damaris brings an orphaned puppy home to the shack she shares with her fisherman husband. In Quintana and Dillman’s deliberately flat, affectless prose, we learn that Damaris and her husband don’t sleep in the same bed anymore, and that at 39 years old, Damaris has no other close family. She’s lonely. She wants someone to love.

I don’t want to spoil the plot of this book too much. But if you’re the kind of person who doesn’t care to read about animals experiencing physical hardships, I will reiterate that The Bitch is both sardonic and pitch-black, and then ask you to do some mental math here.

When the dog is a puppy, Damaris is happy to carry her around in her bra and lavish her with love and affection. But the dog soon grows up enough to begin asserting a will and independence of her own. And Damaris, who has never gotten good results in life from asserting her own will, does not react well. What ensues is written with such viciousness that it slices all the way down to the bone.

—Constance Grady

Minor Detail by Adania Shibli, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette

In tone and style, Minor Detail almost feels like two separate books. The first half recounts an Israeli war crime in stark, impassive third person, before the second half veers sharply into an almost-too-intimate narration of the instability and horrors of Palestinian life under the modern Israeli occupation. The only link, at least in plot, is our unnamed second protagonist’s obsessive interest in the rape and murders laid out in the first part of the book.

It’s jarring, almost, the transition between the two halves. And standing alone, neither would work. Together, they weave a tense, haunting story — one in which violence echoes, the stories of the voiceless go untold as a rule, and memory is short for the victor.

This story is told not with dialogue, or even much plot, but with detail. Adania Shibli’s intense focus on small details — writing about “the fly shit on a painting and not the painting itself,” as the saying goes and our second Palestinian narrator echoes — offers some tiresome moments to trudge through, but also moments that are compellingly realistic. Don’t leave as the psychopathic Israeli commander methodically washes himself for the fifth time. Stay for the intense irritation from the dust caused by a bombing. Stay for the half-mournful, half-honorific recitation of each Palestinian village literally wiped off the map in the last 70 years. Stay for the minor details, up until the abrupt ending.

—Caroline Houck, deputy Washington editor

Young People’s Literature

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22045534/King_and_the_Dragonflies_Cover.jpg) Scholastic Press

Scholastic PressKing and the Dragonflies by Kacen Callender

King and the Dragonflies is a sweetly tender middle-grade novel that feels like it’s already classic. You could have pulled it off the table at the Scholastic Book Fair 20 years ago and it would have felt right — except Kacen Callender’s understanding of race, sexuality, and identity is a lot more nuanced than anything I remember reading 20 years ago.

King is pretty sure his older brother Khalid is a dragonfly now. Khalid died a few months ago — a freak heart attack out of nowhere — but every day, King walks out of his small-town Louisiana school and into the bayou, where millions of dragonflies swarm, and tries to figure out if one of them is Khalid. He can’t hold on to the idea in his head that Khalid might be gone for real.

But then King’s ex-best friend Sandy runs away and turns up in King’s backyard, and King has to decide how he feels about that. He’s one of the only people who knows Sandy’s deepest secret, which is that Sandy is gay. Sandy, in turn, is one of the only people who knows King’s deepest secret, which is that Khalid might be gay, too. And King is the only person left alive who knows how Khalid — beloved, vanished Khalid — reacted to that possibility.

King is all tangled up in the knots of his identity. It’s both cathartic and joyful to watch Callender, with great gentleness and generosity, begin to untangle him.

—Constance Grady

We Are Not Free by Traci Chee

In We Are Not Free, Traci Chee takes a sprawling approach to the Japanese internment camps of 1940s San Francisco. Chee writes from the point of view of 14 teenagers, ages 14 to 20: angry, rebellious Frankie; Bette, who imagines her life as a glamorous white movie star; artistic Minnow; and more, all of whom spent time in one of the dozens of camps set up to incarcerate Japanese Americans after the Pearl Harbor bombing.

In the novel’s first section, we watch Chee’s characters intersect with each other through family connections, friendship, or bonds formed in the camps. Then the novel leaps several years ahead to show how, once these teens return to their homes, their lives were irrevocably altered.

We Are Not Free is thoroughly researched and teeming with historical detail. Chee captures everything from the mundanity of some days in the camps to the “loyalty questionnaire” those held captive were forced to answer to pledge their allegiance to the United States. The depth and spread of the novel feel like a necessary corrective to the fact that this chapter of American history is largely overlooked. As Chee bounces compellingly from voice to voice, it becomes clear that no two characters experienced this traumatic event in the same way. Which stands in total contrast against the uniformity with which they were treated, simply because of their race.

—Karen Turner, identities associate editor

Every Body Looking by Candice Iloh

Few experiences are as universal — or as excruciating — as the feeling, as you transition from childhood to adulthood, of being utterly uncomfortable in your own skin. Your body betrays you; your emotions betray you; the rules and expectations others impose on you hem you in like a too-tight sweater. This is the stage at which we meet Ada, 18, the heroine of Every Body Looking.

Ada recently graduated from high school, where she was, she says, “one of few specks of dingy brown in a sea of perfect white,” and is now headed to a historically Black college, eager to be away from the strict rules of her devout father’s household and the chaotic hurt caused by her troubled mother. She’s sharp and observant and unsure of herself and her place in the world, shy but bright with yearning.

The book, told as a series of prose poems, follows Ada from graduation day to college, before jumping back in time to various points in her childhood. The text follows the shape of her thoughts, fragmented on the page, words bumping up against each other or forming a gentle curve to echo the lines of a dancer’s feet she sketches over and over, the symbol of a dream she barely dares to articulate, even to herself. And through her thoughts, a portrait emerges of a young woman struggling with issues both universal — wanting to be liked, to feel seen, to make a friend — and specific to the experiences of a Black woman and child of immigrants.

As its title signals, the body is a big theme of Every Body Looking, and Ada fixates on hers: on how it is both too much and not enough, on its strengths and limitations, on the buried traumas it carries. The final page sees her make a decision we don’t learn the outcome of; but every step Ada has taken along the way toward trusting her body, toward embracing the things she wants and not conforming to others’ expectations, adds up to something gently triumphant all the same.

—Tanya Pai, style and standards editor

When Stars Are Scattered by Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed

When Stars Are Scattered is the most vibrant and approachable take on life as a refugee that anyone is likely to put together. Carefully crafted by Victoria Jamieson after extensive interviews with former refugee Omar Mohamed, this vibrant graphic novel tracks Omar through his childhood in a refugee camp in Kenya after he escapes Somalia’s civil war with his nonverbal little brother, Hassan.

Omar, whom Jamieson represents to us as a likably squishy-faced figure in bright red, is immediately endearing: a smart kid trying his best in rough circumstances, whose temper occasionally and understandably gets the best of him. But his real job in When Stars Are Scattered is to offer us a window into the peculiar social ecosystem of a refugee camp, with all its infuriating bureaucracy and scarcity.

Omar spends his days looking after Hassan, who sometimes has seizures and is vulnerable to thievery if he wanders away from the safety of their particular block. Omar helps his foster mother sweep the dirt floors of their tents and brew tree bark tea for hunger pangs. He plays soccer with his friends, using a ball made out of plastic bags. Eventually, he makes it to the camp school, where he is the object of much envy for having a workbook and pencil to take notes with. He watches with envy those few refugees who find themselves summoned to the UN to discuss resettling, and when he himself makes it onto the resettlement list, years pass between each interview.

Today, Omar Mohamed is a US citizen who works to help people through the crisis he once lived. When Stars Are Scattered reads like an extension of that project: a straightforward, accessible way to show American children in their classrooms what is happening out in the world right now, to children just like them.

—Constance Grady

The Way Back by Gavriel Savit

Gavriel Savit’s darkly charming folktale The Way Back has the feel of Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain, condensed into a single book. Just as Alexander’s five-book series built an original plot around figures from Celtic mythology, Savit tells a story rooted deeply in Jewish folklore, placing his original characters among mythical demons and other supernatural forces. The book’s narrative has an irresistible momentum that nevertheless sometimes succumbs to overcrowding.

The Way Back opens with a chapter that collapses three generations of a family into a few pages, before letting us meet its real protagonists, a girl named Bluma and a boy named Yehuda Leib. Both live in a tiny town in Russia somewhere in the late 1800s, and both grapple with considerable losses early in the book. Those losses send them flitting between this world and the next, in a quest to find a way to cheat Death itself. (This is the kind of book where Death is a main character.)

Savit is an often gorgeous writer, and his sentences have the cadence of someone telling you a story out loud. At times, I felt as though The Way Back was in such a hurry to get where it was going that I didn’t entirely tap into the emotions of the characters. But the book’s world is peopled with so many interesting figures and its plot is so engaging that I was always on to the next thing before I could really register my complaints.

—Emily VanDerWerff

Author: Vox Staff

Read More