Here’s what you need to know today.

The first coronavirus death in the United States may have been weeks earlier than anybody thought.

The first deaths attributed to the coronavirus in the US were recorded on February 26 in a suburb of Seattle, Washington. Until now.

On Tuesday, officials in Santa Clara County, California, announced that autopsies of two individuals who died in their homes on February 6 and February 17 show that they died from Covid-19.

This dramatically alters the timeline of when, and how, the virus spread in the United States before the explosion of cases the country saw in March and April. And it could help the country better prepare for a possible second wave of the coronavirus, which the director for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned Tuesday could arrive in the winter and be “even more difficult than the one we just went through.”

But if and when that second waves happens, if you happen to receive a text message from a friend of a friend who’s uncle works for Homeland Security and is worried about a looming nationwide lockdown, you should definitely think twice before rushing out to buy 30-packs of toilet paper — because that text message might have been spread by Chinese operatives.

Here’s what you need to know today.

America’s first coronavirus death may have been in early February

The timeline for the coronavirus in the United States is shifting. On Tuesday, health officials in Santa Clara, California, said autopsies for two individuals showed they had died from Covid-19 in early and mid-February.

Originally, the US’s first recorded death was believed to be in Kirkland, Washington, on February 29, but that was later updated after officials linked two deaths on February 26 to the coronavirus. The examination was based on testing tissue samples, which were confirmed by the CDC.

But now, according to Santa Clara County officials, the first death actually occurred on February 6. The second came on February 17, more than a week earlier than the victims in Washington state.

Sara Cody, the county’s public health officer, said that the individuals who died did not have any known travel histories, including to China, that would have exposed them to the virus, though more investigation might still be needed.

This suggests the coronavirus was spreading in communities in the United States far earlier than officials may have anticipated. “Each one of those deaths is probably the tip of an iceberg of unknown size,” Cody said in an interview with the New York Times. “It feels quite significant.”

The coronavirus crisis is fast-moving, and the lack of widespread testing — especially in the early weeks of the pandemic, when testing narrowly focused on people who had traveled to China — means that cases of coronavirus went undiagnosed, and deaths from the virus almost certainly have gone unrecorded.

CDC warns of a “second wave” of the coronavirus

On Tuesday, CDC director Robert Redfield said in an interview with the Washington Post that another wave of the coronavirus this winter could be far more deadly for the United States.

“There’s a possibility that the assault of the virus on our nation next winter will actually be even more difficult than the one we just went through,” Redfield said. “And when I’ve said this to others, they kind of put their head back, they don’t understand what I mean.”

The coronavirus is already taxing the US health care system as hospitals struggle to acquire enough personal protective gear to keep workers healthy and to expand capacity to treat patients who may need hospital or ICU beds and ventilators.

But the coronavirus only really began to spike in late March and April in the United States, toward the end of what’s considered flu season. (The CDC describes the flu as traditionally peaking between late December and February.)

If a second wave of coronavirus cases were to hit this winter, at the same time the flu is raging, the situation could get even more dire.

The flu accounts for between 12,000 and 61,000 deaths in the US annually, according to CDC data, and between 140,000 to 810,000 hospitalizations. Add a bad flu season to the coronavirus pandemic — which has killed at least 45,600 Americans since at least February — and it could cripple health systems across the country. (Americans don’t stop having heart attacks and strokes in a pandemic, either.)

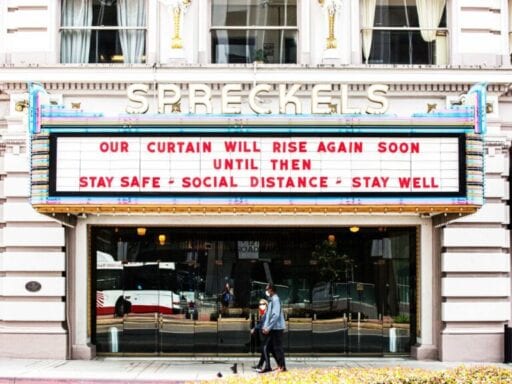

Redfield warned that states and local governments need to prepare now, but it’s a reminder of just how much worse this coronavirus outbreak can be, especially as some groups and states agitate to lift stay-at-home orders.

There is still no proven treatment for the coronavirus, and a vaccine is unlikely to be available for, in the rosiest of estimates, at least a year. Americans may very well have to shut down once again, maybe for even longer periods of time — which means even if economies start to reopen and infections diminish right now, testing, contact tracing, and stockpiling of critical supplies all need to keep happening.

That scary text message about an impending national lockdown? Chinese intelligence might have helped spread it.

In mid-March, as US states began shutting down businesses, canceling mass events, and closing schools, text messages began circulating warning the Trump administration was about to implement a national lockdown.

The National Security Council described these message as “FAKE” (and despite the Trumpian language, they were, in fact, fake) and asked people to follow CDC guidance.

Now, the New York Times is reporting that Chinese agents may have tried to amplify and spread those messages, though US intelligence officials do not believe Beijing created them.

Since that wave of panic, United States intelligence agencies have assessed that Chinese operatives helped push the messages across platforms, according to six American officials, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to publicly discuss intelligence matters. The amplification techniques are alarming to officials because the disinformation showed up as texts on many Americans’ cellphones, a tactic that several of the officials said they had not seen before.

It turns out China has a pretty good playbook to borrow from, specifically the Russian government’s attempts to spread misinformation online during the 2016 election.

A coronavirus pandemic that scientists are trying to learn about in real time and about which even official health guidance is changing as new facts emerge is the perfect petri dish for misinformation to spread and take hold. Especially when it’s amplified by people in positions of power.

The tensions between the US and China over the coronavirus are growing, with both Democrats and Republicans seeking to hold Beijing accountable for its mishandling of the virus. The Trump administration and the president’s Republican allies are also trying to shunt blame for their own missteps in the early days of the crisis.

China has been publicly promoting conspiracy theories against Americans and foreigners in general in an attempt to deflect blame for its failures in containing the virus; but it seems the Chinese government may also be using more low-key disinformation tactics to sow chaos and seed distrust in institutions.

In the middle of both a public health and an economic crisis, this is particularly dangerous, as access to real, accurate information is literally a matter of life and death.

And some good news

It’s Earth Day. And while most of us can’t fully enjoy the glories of the planet while in lockdown, the effects of shutting humans in their homes has given the planet some literal breathing space. The animals are coming out. Air pollution has fallen sharply.

As Vox’s Umair Irfan, Brian Resnick, and Eliza Barclay explain:

Air pollution is a deadly threat, killing millions around the world every year. It’s also linked to more severe outcomes for Covid-19. Conversely, the economic slowdown stemming from Covid-19 showed that reducing pollution yields massive benefits for public health. One researcher estimated that the drop in air pollution in China saved 20 times as many lives as were lost to the virus.

And China isn’t the only place seeing clearer skies. In the United Kingdom, nitrogen dioxide pollution fell 60 percent after the country implemented a lockdown compared to the year prior. A nationwide lockdown in India revealed skylines and mountain vistas that had been obscured for decades.

Of course, the social, economic, and public health costs of the coronavirus are not exactly a sustainable trade-off. But at the very least, post-pandemic, the world might start to wonder if there can’t be a balance between a healthy economy and a healthier planet.

“[I]t’s worth asking why we tolerated so much dirty air for the sake of the economy for so long and whether there’s a better way,” the Vox writers note.

I mean, look at the views!

What nature really is and how we screwed it up.

This is Dhauladhar mountain range of Himachal, visible after 30 yrs, from Jalandhar (Punjab) after pollution drops to its lowest level. This is approx. 200 km away straight. #Lockdown21 #MotherNature #Global healing. pic.twitter.com/cvZqbWd6MR

— Diksha Walia (@Deewalia) April 3, 2020

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Jen Kirby

Read More