What did Trump know about the coronavirus? And what did Woodward know?

It’s a Washington tradition for a presidential administration to be roiled by a new book from legendary journalist Bob Woodward.

This time around, though, the headline-grabbing news isn’t from highly placed anonymous sources, but rather from comments that President Donald Trump made to Woodward, on the record, over the course of 18 interviews.

In early February, Trump privately told Woodward that the new coronavirus was “more deadly” than the flu, and that it “goes through air” — as he was publicly suggesting that the virus was similar to the flu. Then, as the virus ravaged New York City in mid-March, Trump told Woodward that he had wanted to “play it down.”

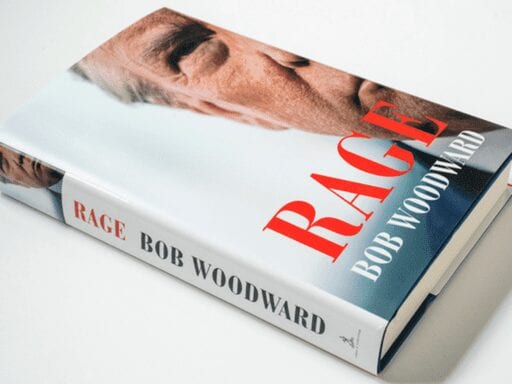

Woodward taped these comments from Trump, and CNN published excerpts of the tapes in the lead-up to the September 15 release of the new book, Rage. Widespread outrage ensued — some aimed at Trump, some aimed at Woodward himself for not publishing this apparently newsworthy material months ago. I’ve now read the full book, so here’s a guide to its revelations and the controversies surrounding it.

What is a Bob Woodward book?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21880431/GettyImages_1031447930.jpg) Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Justin Sullivan/Getty ImagesWoodward rose to fame as half of the Washington Post’s “Woodward and Bernstein” reporting duo that helped expose the Nixon administration’s Watergate cover-up — triggering a scandal that led to Nixon’s resignation. But in recent decades, Woodward’s main reporting interest has been using his Washington connections to report and write books about what’s going on in the highest levels of the US government, especially the presidency. (He has written two books on the Clinton administration, four on the George W. Bush administration, two on the Obama administration, and now two on Trump.)

The books have tried to put readers “in the room,” depicting what happens behind closed doors. To do that, Woodward relies on the cooperation and anonymized accounts of top-level government officials. He then presents a narrative, based on sources and sometimes documents, in an omniscient style, but largely focused on certain characters.

One oddity of his approach is that the identities of his major sources often seem very obvious, because he goes on at great length about certain people’s “thoughts,” but not others. His last book, Fear, appeared to be mainly told from the perspectives of four since-departed White House officials — Rob Porter, Gary Cohn, Steve Bannon, and Reince Priebus — as well as Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and Trump’s former lawyer John Dowd.

At their best, Woodward’s books are deeply revealing about policymaking and government. But his critics have long argued that his accounts, far from being neutral, are heavily skewed toward his major sources’ points of view and priorities, and portray those who didn’t talk as ciphers or villains. The reality is a bit more nuanced (talking a lot doesn’t guarantee you a good portrayal, as Trump found here), but his readers are absolutely getting a particular version of what happened, as told by particular people.

What is Woodward’s new book about?

As Woodward explains, the plan for Rage changed while he was working on it, and the book is basically divided into two halves.

The book’s first half touches on several topics related to national security, most prominently Trump’s threats to and subsequent diplomacy with North Korea. The major sources here appear to be former Secretary of Defense James Mattis, former Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats, and former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson (or people close to them).

These three officials’ difficult relationships with the president, their doubts about the president, and their eventual departures from the administration are all chronicled. We also get a few brief detours into other topics, such as former Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein’s version of why he appointed Robert Mueller as special counsel in the Trump-Russia investigation.

Then, as the book’s second half begins, two things happen at around the same time: President Trump does the first of an eventual 18 interviews with Woodward, and the Covid-19 pandemic breaks out. So Woodward’s attention shifts to chronicling the US’s response to the pandemic, but he also intersperses whatever Trump happens to be telling him on that as well as sundry other topics.

The main characters and likely sources here, besides the president, are National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien, Deputy National Security Adviser Matthew Pottinger, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Director Robert Redfield, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Director Anthony Fauci. Trump’s son-in-law and adviser Jared Kushner also gets some attention, though the sourcing of the material about him is less clear.

As for the title, it’s a reference to a Trump quote in a 2016 Woodward interview, in which he said “I bring rage out” in people.

What’s the biggest news from the book?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21880436/GettyImages_1216055255.jpg) Win McNamee/Getty Images

Win McNamee/Getty ImagesBy far the most attention-getting news from the book has been Trump’s comments on the coronavirus.

On February 7, Trump called Woodward and surprisingly brought up the coronavirus when there were few confirmed cases in the US, and when impeachment had been dominating the news. Trump opened by saying that there was “a little bit of an interesting setback with the virus going on in China,” and that he’d spoken with President Xi Jinping the previous night.

“We were talking mostly about the virus, and I think he’s gonna have it in good shape, but it’s a very tricky situation,” Trump said. “It goes through air, Bob, that’s always tougher than the touch. … You just breathe the air and that’s how it’s passed.”

He continued: “That’s a very tricky one. That’s a very delicate one. It’s also more deadly than even your strenuous flus.” Apparently speaking about mortality rates, he says: “This is 5 percent versus 1 percent and less than 1 percent. You know? So, this is deadly stuff.” However, he went on to say that he thinks the Chinese have it under control, and that “I think that that goes away in two months with the heat,” because “as it gets hotter that tends to kill the virus.”

Here, and notably early, Trump is saying (in private) both that the virus can spread through the air and that it’s very deadly and dangerous. This is quite different from what he was saying in public. In the coming weeks, Trump would publicly say the virus was similar to the flu, and would argue that mortality rates wouldn’t be so high.

Then, in another conversation with Woodward on March 19 — once New York City was reeling from the virus, the country had begun to shut down, and Trump’s public commentary had become more pessimistic — Woodward asked Trump when his thinking on the seriousness of the threat had changed. “I wanted to always play it down,” Trump said. “I still like playing it down, because I don’t want to create a panic.”

These comments — which can be heard on tapes provided to CNN — have gotten enormous attention. Many interpreted them, together, as Trump revealing he fully understood the threat of the virus, and then confessing that he deliberately misled the American public about that threat. Overall, Woodward concludes, as he said in an interview with NBC, that Trump “possessed specific knowledge that could have saved lives” had he made it public earlier.

Did Bob Woodward possess specific knowledge that could have saved lives?

News of Trump’s comments to Woodward first got out last Wednesday, as part of a promotional push in advance of his book’s release Tuesday.

And very quickly, Woodward started to get asked why he saved the tapes — recorded in February and March, for his book release in September, rather than publishing them at the time, when the pandemic was beginning in the US.

“For months many dismissed serious/need for distancing/need for masks, citing Trump,” Wesley Lowery, a former Washington Post journalist now at CBS News, tweeted. “Reporting that Trump said privately how deadly COVID is/that it spread airborne could have changed those people’s behavior & saved lives.” Meanwhile, Charles Pierce, writing for Esquire, claimed that Woodward knew “the truth” and “kept it to himself because he had a book to sell.”

Trump himself has embraced this line of criticism as well, though his point was to argue that Woodward’s slowness to publish reveals his comments aren’t as bad as critics are saying:

Bob Woodward had my quotes for many months. If he thought they were so bad or dangerous, why didn’t he immediately report them in an effort to save lives? Didn’t he have an obligation to do so? No, because he knew they were good and proper answers. Calm, no panic!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 10, 2020

Woodward has offered a few points in response. For one, he told the Washington Post’s Margaret Sullivan he wasn’t sure whether Trump’s February comments about the virus’s severity and airborne spread was accurate — and he feared that rushing to publish unsourced Trump claims could have spread misinformation about the virus. For instance, in the same call with Woodward, Trump also mused that the virus would probably go away in warmer weather, which did not happen. Also, even weeks after these Trump comments, public health officials like Fauci were saying the virus posed little threat to the US.

Some have pointed to Trump’s comment that the virus spreads through “air” as a particularly significant bit of life-saving information that Trump knew early. Debate raged for months over whether the virus spread primarily through “droplets” (small particles that linger briefly in the air) or also through “aerosols” (even smaller particles that can float longer in the air). The World Health Organization didn’t officially acknowledge until July that aerosol transmission may occur.

Yet Woodward does not unearth any briefing or call where Trump is told about airborne spread, and Trump’s fuller comments are contrasting a virus you can get when you “breathe the air” with one you get through “the touch” (like, for instance, Ebola). So it’s not clear if Trump actually had substantive information here and if so where he got it, or whether he was using a layman’s description of droplet transmission (since after all, droplets are in the air). Trump himself said last week that “everyone knew” the virus was transmitted through the air at the time — which is true about droplets, though not aerosols.

Woodward’s defense for waiting to publish also hinges on the timeline of his reporting as Trump’s various phases of responses to the virus. In February, Trump was publicly downplaying the threat, and then, Woodward says, he hadn’t accomplished the reporting necessary to confirm what Trump told him in private. Then, by mid-March (when Trump admitted to Woodward he had liked to “play it down”), Trump had adopted more serious public rhetoric on the virus’s threat and was encouraging social distancing, and it was evident to everyone that it was deadly.

Trump later pivoted away from this stance, and back toward denialism and downplaying later in the spring. And Woodward said he finally got sources to reconstruct some of Trump’s early coronavirus briefings in late May. So Sullivan asked Woodward why he didn’t publish the tapes then, when Trump was back in denial mode. Woodward’s answer was that he conceived of this reporting as for a book, wanted it released in book form, and wanted it timed before the election.

What else is in the book?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21880440/GettyImages_1172083503.jpg) Steven Ferdman/Getty Images

Steven Ferdman/Getty ImagesThe newsworthy material in Rage falls into two main categories: stuff Woodward’s sources provided, and comments Trump himself made. In the former category, we learn:

- As the US and North Korea exchanged threats in mid-2017, Mattis thought an accidental war was far more likely than most Americans understood at the time.

- Dan Coats, Trump’s former director of national intelligence, deeply suspected throughout his tenure that “Putin had something on Trump” (but also saw no evidence to back that up).

- Mattis and Coats spoke in May 2019 (after Mattis had resigned but while Coats was still in the administration), and Mattis called Trump “dangerous” and “unfit,” and suggested they speak out together against him. (They didn’t.)

- After Trump turned toward diplomacy with North Korea, Kim Jong Un wrote him 27 fawning letters that Woodward obtained and reviewed. (The main takeaway is that Kim can be an enthusiastic flatterer.)

- As the coronavirus spread in late January and February, top National Security Council officials sounded the alarm the loudest due to distrust of China.

- Meanwhile, top health officials like Fauci and Redfield were slower to grasp the gravity of the situation, and in February they often made ominous comments in private but downplayed the threat of the virus in public.

As far as Trump’s own comments, beyond the pandemic material, here’s what stands out in all the rambling:

- When Woodward asked whether “white, privileged people” like him and Trump needed to try harder “to understand the anger and pain” that “Black people feel in this country,” Trump responded mockingly, saying that Woodward had “really drank the Kool-Aid” and that he didn’t share that belief at all.

- Trump bragged to Woodward that he’s “built a nuclear — a weapons system that nobody’s ever had in this country before,” and Woodward subsequently confirmed from sources that the US did have “a secret new weapons system.” (It’s unclear what this is about, though there are theories.)

Finally, Woodward arrives at the conclusion that Trump is “the wrong man for the job,” an assessment delivered with much gravity from a sober-minded reporter, but one that can hardly be a surprise for many readers.

Why did Trump talk to Woodward?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21880442/GettyImages_1228442972.jpg) Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Drew Angerer/Getty ImagesBoth the president’s allies and his critics have been baffled that he spent so much time talking to Woodward in such an unguarded way. Fox News host Tucker Carlson tried to place the blame on Lindsey Graham for convincing Trump to cooperate, but Graham didn’t force Trump to talk to Woodward 18 separate times — this was Trump’s decision. Indeed, Trump several times called Woodward out of the blue to talk, without anything officially being scheduled.

The explanation for Trump’s chattiness is probably pretty simple: He refused to talk for Woodward’s last book, didn’t like how that one turned out, and therefore wanted to at least try to charm and spin him this time. He was fully aware that it might not work, and mentioned that possibility to Woodward in real time, repeatedly musing that the book would make him look terrible. (Referencing former President George W. Bush, Trump said, “He spent all that time with you, and you made him look like a fool.”)

It’s also possible that Trump was misled by the Washington conventional wisdom that people who talk to Woodward get rosier portrayals in his books. There’s some truth to that, but the problem is that Trump didn’t really cooperate in the way Woodward prefers — by walking through his decisions and mentality at key moments in an orderly way, to provide building blocks for the book’s narrative.

Instead, Trump repeatedly ignored Woodward’s specific questions to instead talk about whatever he wanted. For instance, Woodward asked him what he was thinking at the Singapore summit with Kim Jong Un, and Trump said there were a lot of cameras there. Woodward pleaded repeatedly that this would be for “the serious history,” but Trump was unmoved. “He was on his track and he would stay there,” Woodward writes.

The overall effect is that Trump hijacks the book as soon as he starts talking. As a result, much of the book’s second half is an authentic portrait of what it’s like to talk to Donald Trump: scattershot, tedious, frustrating, and occasionally outrageous.

Help keep Vox free for all

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world: Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Andrew Prokop

Read More