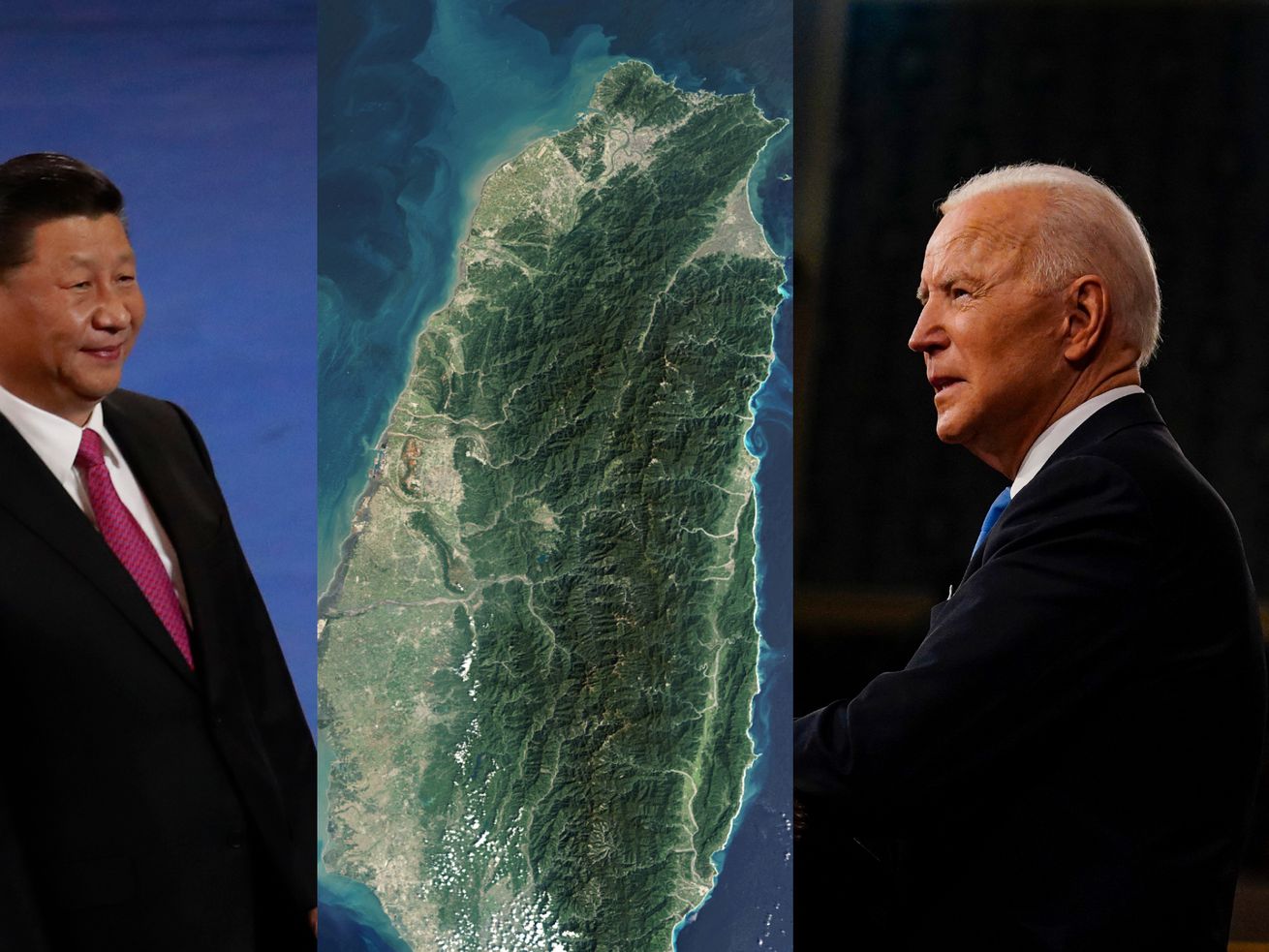

If a war breaks out over Taiwan, Biden may be forced into a decision no American president since 1979 has wanted to make.

No American president has had to choose whether to go to war to defend Taiwan against a Chinese military invasion. President Joe Biden might have the decision thrust upon him.

The outgoing commander of US forces in the Indo-Pacific region, Navy Adm. Philip Davidson, told US lawmakers in March that he believes Beijing will attempt a takeover of the neighboring democratic island — which it considers part of mainland China — within the next six years. Davidson’s successor, Navy Adm. John Aquilino, expressed a similar concern days later.

“This problem is much closer to us than most think,” he told members of the Senate Armed Services Committee. “We ought to be prepared today.”

The four-stars’ predictions aren’t wholly shared by everyone in the administration. “I’m not aware of any specific timeline that the Chinese have for being able to try and seize Taiwan,” said one senior US defense official, who, like others in the administration, spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive foreign policy issue.

“I’m not concerned that in the near term we’re going to see a significant escalation,” a senior administration official told me, though they added that “any unilateral move to change the status quo, as well as a move to change the status quo by force, would be unacceptable regardless when it happens.”

Experts I spoke to also felt Davidson and Aquilino’s claims are too alarmist and may be in service of trying to boost defense spending for operations in Asia.

But all agree that China is a more credible threat to Taiwan today than in the past. Beijing flaunts it, too. In recent weeks, China sent 25 warplanes through the island’s airspace, the largest reported incursion to date, and had an aircraft carrier lead a large naval exercise near Taiwan.

These and other moves have some worried that Chinese President Xi Jinping might launch a bloody war for Taiwan. He hasn’t been subtle about it, either. “We do not promise to renounce the use of force and reserve the option to use all necessary measures,” Xi said two years ago.

Should Xi follow through with an all-out assault, Biden would face one of the toughest decisions ever presented to an American president.

It’s therefore worth understanding the history behind this perennial issue, how the US got into this predicament, and whether the worst-case scenario — a US-China war over Taiwan — may come to pass.

The inescapable tension at the heart of US policy toward Taiwan

The roots of the current predicament were seeded in the Chinese civil war between the communists and the nationalists.

When World War II ended in 1945, the longtime rival factions raced to control territory in China ceded by Japan after its surrender. The communists, led by Mao Zedong, won that brutal conflict, forcing Chiang Kai-shek’s US-backed nationalists in 1949 to flee to the island of Taiwan (then called Formosa) off the mainland’s southeastern coast.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22489285/514870652.jpg) Agence France Presse/Getty Images

Agence France Presse/Getty ImagesInitially, the US was resigned to the idea that Taiwan would eventually fall under communist China’s control, and President Harry Truman even refused to send military aid to support the nationalists.

The Korean War, launched in 1950, raised Taiwan’s importance to the United States. The Truman administration abhorred that a communist nation, North Korea, could invade a sovereign state like South Korea. Worried Taiwan might meet a similar fate, the US president quickly sent the 7th Fleet toward the island as a protective and deterrent force.

Military and economic aid soon followed, and both governments signed a mutual defense treaty in 1954. The US also provided intelligence support to Taiwan’s government during flare-ups with China in the 1950s.

“Taiwan went from being not interesting to the front lines of the global confrontation with Communism,” said Kharis Templeman, a research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution.

Ironically, it would be the American fight against communism — the Cold War — that would see the US government change its Taiwan policy yet again.

Starting around 1960, a wedge formed between the Soviet Union and mainland China over ideological and geopolitical interests. To widen the gap between them (and get some help from Beijing during the Vietnam War), President Richard Nixon and his team sought a rapprochement with the Chinese communists in the early 1970s.

During Nixon’s historic trip to China in 1972, he and Chairman Mao Zedong issued the Shanghai Communiqué, which stated the US “does not challenge” the belief “that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China.” Importantly, the US didn’t say it “agreed” with that position.

President Jimmy Carter’s administration later made an official change: In January 1979, the US recognized “the Government of the People’s Republic of China as the sole legal Government of China,” and the two countries established formal diplomatic relations. At the same time, Carter terminated America’s official ties to Taiwan.

But Republicans and Democrats in Congress were unhappy with the president’s decision. Only three months later, lawmakers — including then-Sen. Joe Biden — passed the Taiwan Relations Act, which codified into law a continued economic and security relationship with the island.

It formalized that “the United States shall make available to Taiwan such defense articles and defense services in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capacity as determined by the President and the Congress.”

The law also stated that “any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means” would be “of grave concern to the United States.”

That sounds like a stark warning to Beijing. But, importantly, the US never stipulated that it would come to Taiwan’s defense during a military conflict, only that it would help the island defend itself and would be concerned if such an event happened.

Keeping that part ambiguous — strategically ambiguous, that is — allowed Washington to maintain its newly formal relations with mainland China while not abandoning Taiwan.

The Taiwan Relations Act (or TRA, as the law is more commonly known) remains the basis of the US-Taiwan relationship to this day.

“It is the TRA that embodies the ambiguity that we have in our policy,” said Shirley Kan, a Taiwan expert for the Congressional Research Service from 1990 to 2015. “It is the law of the land and it has legal force.”

(There are other documents often referenced when detailing America’s relations with China and Taiwan, like the “Three Communiqués” between Washington and Beijing and the “Six Assurances” President Ronald Reagan gave to Taiwan. The communiqués underscore how the US “acknowledges” China’s claims on Taiwan, and the assurances made clear the US wouldn’t abandon the island or make it negotiate with Beijing for reunification. The TRA, however, is the only one of these documents signed into US law.)

There’s an obvious tension here: The US recognizes “one China” but is close to both Beijing and Taipei. It was always going to put administrations in Washington in an awkward position, let alone US officials in those capitals.

It explains why the US-China-Taiwan relationship is such a delicate balancing act, one that not everyone’s convinced Washington should have engaged in.

“We have an interest in Taiwan because we have a commitment, we don’t have an interest because it’s important to our security,” said Robert Ross, a professor of political science at Boston College. “We’re living with the fiction that we don’t have a ‘two China’ policy.”

Fiction or not, it’s the policy on the books — and it’s caused headaches for all involved ever since.

“It’s a fairly convoluted political Band-Aid over an irreconcilable problem,” said Daniel Russel, the top State Department official for East Asian affairs from 2013 to 2017. “We don’t have a new policy because there are no other options.”

“This is the quiet before the storm”

A policy of “strategic ambiguity” — as the US policy toward Taiwan is known — is all well and good, until the US president has to actually decide whether to defend Taiwan.

A barrage of missile strikes and hundreds of thousands of Chinese troops landing on Taiwan’s beaches would force Biden to make a choice: wade into the fight against a nuclear-armed China, or hold back and watch a decades-long partner fall.

The first risks countless American, Chinese, and Taiwanese lives and billions of dollars in a fight that many believe the US would struggle to win; the second risks millions of Taiwanese people coming under the thumb of the Chinese Communist Party, losing their democratic rights and freedoms in the process, and Washington’s allies no longer considering it reliable in times of need.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22489297/1302221268.jpg) An Rong Xu/Getty Images

An Rong Xu/Getty ImagesFormer officials who wrestled with this question know it’s not an easy call. “You’re damn right it’s hard,” Chuck Hagel, who served as secretary of defense when Biden was vice president, told me. “It’s a complex decision for any administration, not an automatic one. You can talk policy all you want, but a war off the coast of China? Boy, you better think through all of that.”

Taiwan’s government has certainly thought about it, and it’s concerned about what may be coming.

“We treat any threat from China as imminent, so we have to prepare for any contingency in this area,” a source close to Taiwan’s administration told me, speaking on condition of anonymity to speak freely about the government’s thinking. “It could be any time. It could be in the next six months or the next six years. The one thing we’re certain about is that China is planning something.”

The US intelligence community assessed something similar. Greg Treverton, who chaired the National Intelligence Council from 2014 to 2017, told me that a Chinese invasion of Taiwan was “more a ‘possibility’ than a realistic option,” though he said he didn’t “remember any specific reports about Taiwan and timetables.”

The Biden administration has done its best to reassure Taiwan and deter Beijing from doing the worst. “It would be a serious mistake for anyone to try to change the existing status quo by force,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken said on NBC’s Meet the Press in April.

Whether it’ll be enough for Biden to avoid making the decision no president wants to make will be a looming question during his presidency. And the world may get an answer sooner rather than later.

“This is the quiet before the storm,” said Joseph Hwang, a professor at Chung Yuan Christian University in Taiwan. “The Chinese government is looking for a good time to push for reunification by force. They just haven’t found the right time yet.”

China’s three red lines

John Culver served in the CIA for 35 years, retiring in 2020 after a distinguished career tracking developments in the Taiwan Strait, the 110-mile body of water separating Taiwan and China — the area most likely to serve as the key battleground in a war.

What he told me is that China, at least for now, begrudgingly accepts the situation that it’s in. But Beijing has made clear it has three “red lines” that, if crossed, “would see China go to war tomorrow.”

The first is if Taiwan were to try to formally separate from China and become a sovereign state. Since China considers the island part of the country, any formal independence effort could see Beijing mobilize its forces to stop such an outcome.

The second red line is if Taiwan were to develop the capability to deter a Chinese invasion on its own, namely by trying to acquire nuclear weapons. This has been a contentious issue in the past. Taiwan has twice started a clandestine nuclear program, and the US has twice pushed Taiwan to shut it down, worrying it could prompt China to attack before the island comes close to acquiring the bomb.

The third is if Beijing were to believe an outside power was getting too cozy with Taiwan. Yes, the US sells Taiwan billions in weapons — fighter jets, rocket launchers, artillery — and holds military exercises with Taiwanese forces, but that’s a step below America (or another country, like Japan) stationing its troops on the island. With Taiwan only 110 miles away from mainland China, such a move might look like the makings of a real military alliance.

None of that would please China, especially President Xi Jinping.

“Actions by either the US or Taiwan that push Xi into a corner and question his legitimacy would make him vulnerable if he didn’t respond forcefully,” said Bonnie Glaser, director of the Asia program at the German Marshall Fund think tank in Washington, DC. “I don’t think China is bluffing — there are red lines.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22489316/1231339555.jpg) Costfoto/Barcroft Media/Getty Images

Costfoto/Barcroft Media/Getty ImagesThis isn’t a hypothetical concern: China has lashed out at Taiwan previously over concerns that it was nearing those lines.

The most recent and serious incident happened in the mid-1990s. In June 1995, Taiwan’s then-President Lee Teng-hui visited his alma mater in the United States, Cornell University.

That might seem innocuous, but to Beijing, the visit of a sitting Taiwanese president to America — the first such visit since the break of formal relations in 1979 — was viewed as a symbolic first step toward eventual independence. A month later, China responded by test-launching six missiles in Taiwan’s direction.

Then, ahead of Taiwan’s first direct and free democratic presidential election in March 1996, China conducted realistic military drills near Taiwan with ships and warplanes. One missile, which some experts said had the capacity to carry a nuclear bomb (though it didn’t in this case), nearly passed over Taipei before landing 19 miles off the island’s coast.

For many, these provocations required a US response. But what exactly that response should be was a delicate decision.

Importantly, the People’s Liberation Army (as China’s military is called) wasn’t overly powerful at the time — one expert called it a “backwater.” Its threats were seen more as political language and not a precursor to invasion.

Beijing’s weakness made it an easier call for the US, led by President Bill Clinton, to send two aircraft carriers near Taiwan for both assurance and deterrence. “We did it as a signal to Taiwan that we’d defend it, but not poke China in the eye,” Randall Schriver, former assistant secretary of defense, who was in the Pentagon at the time working on America’s response to the crisis, told me.

Still, such moves worried some that amassing the largest contingent of naval firepower in the region since 1958 could draw the US into a war. “It was very tense,” an unnamed senior defense official told the Washington Post in 1998. “We were up all night for weeks. We prepared the war plans, the options. It was horrible.”

Ultimately, China backed off and Taiwan held its election. But the crisis put all three actors in the drama on different courses.

China invested heavily in a stronger military to ward off another intervention by America. The US, angered by Beijing’s actions during the crisis, pushed for closer relations with the island. And after the election, Taiwan blossomed into a wealthy democracy and showed signs of moving toward — but not actively reaching for — independence.

That ushered in a precarious status quo that lasted for two decades. But how much longer it will last is becoming an increasingly troubling question. Because the China of today isn’t the same country it was 20, or even 10, years ago. Neither is the US.

China under Xi Jinping is more aggressive — and more powerful

In 2017, President Xi detailed his vision to realize his nation’s “Chinese Dream” by 2049 — the 100th anniversary of the Communist Party’s official leadership of China. One section stands out:

Resolving the Taiwan question to realize China’s complete reunification is the shared aspiration of all Chinese people, and is in the fundamental interests of the Chinese nation. …

We stand firm in safeguarding China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, and will never allow the historical tragedy of national division to repeat itself. Any separatist activity is certain to meet with the resolute opposition of the Chinese people. We have the resolve, the confidence, and the ability to defeat separatist attempts for “Taiwan independence” in any form.

Xi stressed several times his regime’s desire to “uphold the principles of ‘peaceful reunification.’” But officials and analysts question the sincerity of that commitment, especially in light of recent events.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22489322/GettyImages_1171879575.jpg) How Hwee Young/Getty Images

How Hwee Young/Getty ImagesOne reason is Hong Kong: Over the past several years, Xi has moved to usurp the democratic city into its fold by passing a draconian national security law, arresting pro-democracy leaders, changing electoral laws to favor Beijing loyalists, and more.

It’s a bold play. After taking over Hong Kong in a war in the 1800s, Britain returned it to China in 1997 with an important stipulation: The city would partly govern itself for 50 years before falling fully under Beijing’s control. So until 2047, the expectation was that the city and the mainland would operate under the principle known as “one country, two systems” (sound familiar?).

But Xi accelerated that timeline, flagrantly crushing the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong and bringing the city further under the control of the Chinese Communist Party, even in the face of US-led international condemnation and pressure.

It’s one example of how China has no qualms about flexing its muscles these days. But Taiwan has also experienced that flexing even more directly.

In April, China sent one of its two aircraft carriers near Taiwan for what Beijing said was a routine naval exercise. The drills were meant to “assist in improving the ability to safeguard national sovereignty, security, and development interests,” the Chinese navy said, using terminology many believed was aimed directly at Taipei.

Days later, China sent 25 warplanes through Taiwan’s air defense identification zone, airspace governments essentially consider their territory for national security reasons. The move was so provocative that Taiwan scrambled its own warplanes and readied its missile defense systems.

China’s aggressions have steadily increased since last September and are now a near-daily occurrence.

In response to those and other events, Taiwan’s Foreign Minister Joseph Wu offered a startling statement to reporters: “We will fight a war if we need to fight a war, and if we need to defend ourselves to the very last day, then we will defend ourselves to the very last day.“

China’s dim view of the United States is another factor. Chinese officials have felt, over the past decade or more, that America is in economic and political decline, their beliefs bolstered by the 2008 financial crisis and, most recently, the initial bungling of the American Covid-19 response. Moving when the US is most vulnerable might just be too good of an opportunity to pass up, some experts say.

It also doesn’t help that the US has gotten extra cozy with Taiwan lately.

For example, Taiwan’s unofficial ambassador to the US accepted Biden’s invitation to his inauguration, the first envoy to represent the island at a presidential swearing-in since 1979. She even tweeted a video about her attendance in which she declared: “Democracy is our common language and freedom is our common objective.”

Then in March, the US ambassador to the archipelago nation of Palau, John Hennessey-Niland, visited Taiwan, becoming the first sitting envoy to set foot on the island in an official capacity in 42 years. He was there accompanying Palauan President Surangel Whipps Jr., whose government is just one of 15 that recognize Taiwan, on his official trip.

But it was Hennessey-Niland who made the biggest splash during the visit when he referred to Taiwan as a “country.”

“I know that here in Taiwan people describe the relationship between the United States and Taiwan as real friends, real progress, and I believe that description applies to the three countries — the United States, Taiwan, and Palau,” he told reporters.

Beijing likely interprets these and other moves as the US moving steadily closer to Taiwan.

Put all this together and you could have a recipe for disaster.

“China is looking for weakness everywhere and probing the US and Taiwan,” said Shelley Rigger, a professor at Davidson College and author of Why Taiwan Matters: Small Island, Global Powerhouse. “The trendlines are not looking good.”

Not everyone subscribes to the doom and gloom, though.

Take those military flights in April, for instance. Experts who aren’t so concerned note that China routinely conducts nonlethal shows of force, and that the Chinese warplanes crossed through a part of Taiwan’s airspace that’s far from the island, making it less threatening than it could’ve been.

Some experts also point out that Beijing has a lot on its plate right now dealing with the Hong Kong situation, the Covid-19 pandemic, and international pressure over China’s mistreatment of Uyghur Muslims, thus likely putting the Taiwan issue low on the government’s agenda.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22489331/1301386990.jpg) An Rong Xu/Getty Images

An Rong Xu/Getty Images“The relative importance of Taiwan has actually declined,” said Cathy Wu, an expert on the China-Taiwan relationship at Old Dominion University. “There’s actually less chance of war now.” She noted that the people in her hometown of Quanzhou, China, directly across the strait from Taiwan, aren’t gearing up for a fight. What they’re mostly concerned about is rising housing prices.

“There’s just no real risk right now when it comes to a direct confrontation between Beijing and Taipei,” Wu told me, noting that both capitals maintain strong economic links, too.

But even the smallest increase in risk today matters more than it did in the past, when China was weaker. “You pay more attention when a tiger clears its throat than when a Chihuahua strains at the leash,” said Culver, the CIA retiree.

And Taiwan and America are certainly paying attention, given what could be a catastrophic outcome: war.

“We have immense power, but so do they”

War games simulating a US-China military conflict over Taiwan make two things perfectly clear: 1) The fight would be hell on earth, potentially leading to hundreds of thousands of casualties, and 2) the US might not win it.

Experts say the first thing Beijing would most likely do is launch cyberattacks against Taiwan’s financial systems and key infrastructure, possibly causing a water shortage. US satellites might also be targets since they can detect the launch of ballistic missiles.

Then China’s navy would probably set up a blockade to harass Taiwan’s fleet and keep food and supplies from getting to the island. Meanwhile, China would rain missiles down on Taipei and other key targets — like the offices of political leaders, and ports and airfields — and move its warplanes out of reach of Taiwan’s missile arsenal. Some experts believe Beijing would move its aircraft carrier out of Taiwan’s missile range since Chinese fighter jets could just take off from the mainland.

And then comes the invasion itself, which China wouldn’t be able to hide even if it wanted to. To be successful, Xi would have to send hundreds of thousands of troops across the Taiwan Strait for what would be a historic operation.

“The geography of an amphibious landing on Taiwan is so difficult that it would make a landing on Taiwan harder than the US landing on D-Day,” said Ross, the Boston College professor.

Many of Taiwan’s beaches aren’t wide enough to station a big force, with only about 14 beaches possibly hospitable for a landing of any kind. That’s a problem for China, as winning the war would require not only defeating a Taiwanese military of around 175,000 plus 1 million reservists, but also subduing a population of 24 million.

For these reasons, some experts say Taiwan — with US-sold weapons — could thus put up a good fight. China’s military (known as the People’s Liberation Army, or PLA) “clearly would have its hands full just dealing with Taiwan’s defenders,” Michael Beckley, a fellow at Harvard University, wrote in a 2017 paper.

Others agree. Sidharth Kaushal, a research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute in the UK, told CNN in 2019 that “the Taiwanese air force would have to sink around 40 percent of the amphibious landing forces of the PLA” — around 15 ships — “to render [China’s] mission infeasible.” That’s a complicated but not impossible task.

What’s more, the island’s forces have spent years digging tunnels and bunkers at the beaches where the Chinese might arrive, and they know the terrain better than the invaders do.

“Taiwan’s entire national defense strategy, including its war plans, are specifically targeted at defeating a PLA invasion,” Easton told CNN in 2019. In fact, in his book he wrote that invading Taiwan would be “the most difficult and bloody mission facing the Chinese military.”

Even so, most experts told me China would have a distinct advantage in a fight. It has 100 times more ground troops than Taiwan and spends 25 times more on its military. Even former top Taiwanese soldiers worry about the island’s defenses.

“From my perspective, we are really far behind what we need,” Lee Hsi-min, chief of the general staff of Taiwan’s military until 2019, told the Wall Street Journal in April. (It’s for this reason that Taiwan’s government consistently requests more weapons as laid out in the TRA.)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22489334/1230681856.jpg) Walid Berrazeg/SOPA Images/LightRocket/Getty Images

Walid Berrazeg/SOPA Images/LightRocket/Getty ImagesBecause of China’s power, proximity to Taiwan, and Taiwan’s weaker forces, most analysts I spoke with say Beijing would come away with a victory. “It’s more or less impossible to stop. Taiwan is indefensible,” said Lyle Goldstein of the US Naval War College. “I think China could go tomorrow and they’d be successful.” When there’s just over 100 miles for a stronger nation to get across, “good luck to the small island,” he added.

This is why the question of America’s support in such a war is so big, and why a decision for Biden would be so weighty. Knowing all this, Biden — or any American president — would likely have to decide whether to intervene to keep Taiwan from losing.

That’s risky, because many believe the US might not succeed at fending off an invasion. China has advanced its missile arsenal to the point that it’d be difficult to send fighter jets and aircraft carriers near the war zone. US bases in the region, such as those in Japan hosting 50,000 American troops, would come under heavy fire. US allies and friends like Australia, South Korea, or even the Philippines could offer some support, but their appetite for large-scale war might not be so high.

It’s a troubling scenario — one in which thousands of Americans could die — that US defense and military officials see over and over again in simulations.

“You bring in lieutenant colonels and commanders, and you subject them for three or four days to this war game. They get their asses kicked, and they have a visceral reaction to it,” David Ochmanek of the Pentagon-funded RAND Corporation told NBC News in March. “You can see the learning happen.”

The best-case war game I found, reported on by Defense News in April, found that the US could stop a full invasion of Taiwan. But there’s a big catch: America would succeed only in confining Chinese troops to a corner of the island. In other words, Beijing would have still pulled off a partial takeover despite the US intervention.

That’s partly why Hagel, the former Pentagon chief, cautions against the US entering such a fight. “I was never sanguine, nor would I be today, about a showdown with the Chinese in that area,” he told me. “We have immense power, but so do they. This is their backyard.”

And, lest we forget, there’s little to no chance that a war over the island wouldn’t spill over to the rest of the world.

“I think it would broaden quickly and it would fundamentally trash the global economy in ways that I don’t think anyone can predict,” Kurt Campbell, Biden’s “Asia czar” in the White House, said on Tuesday.

What would Biden do?

Despite these dire predictions, some analysts I spoke to said the US would simply have no choice but to come to Taiwan’s defense. It might not be mandated by law — the US commitment is ambiguous, after all — but America’s reputation would take a major hit if it let China forcibly annex the island.

“How would other countries see the United States if we don’t come to Taiwan’s aid?” Glaser of the German Marshall Fund said. “We would lose all credibility as a leader and an ally,” especially if Washington didn’t act to support a fellow democracy.

There are some moves short of all-out war Biden could choose, said Schriver, who was also the top Pentagon official for Asia in the Trump administration and is now chair of Project 2049, an Asia-focused think tank.

The US could provide intelligence, surveillance, and logistics support to Taiwan; try to break China’s naval blockade of the island, assisting with logistics and supplies; and deploy its submarine force to augment Taiwan’s naval capabilities.

“It would be an aberration of history if we did nothing, and the PLA would make a mistake to assume that we will do nothing,” Schriver told me.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22489335/1232598743.jpg) Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images

Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty ImagesThe US very well might do something, and the president may even be able to get congressional support for such a war given the strong bipartisan support for Taiwan.

Still, Biden would be the decider about whether or not to put US troops in harm’s way. The responsibility, at least for the next four years, lies with him — and no one is really sure what he’d do.

“Would the US come to Taiwan’s defense? The honest answer is that nobody knows,” said Abraham Denmark, a former top Pentagon official for Asia issues now at the Wilson Center think tank in Washington, DC. “It’s only up to one person. Unless you’re talking to that person, it’s never going to be clear. That’s been true since the late 1970s.”

Biden has a long record on Taiwan, but it’s as ambiguous as America’s Taiwan policy.

As a senator, he voted in favor of the Taiwan Relations Act, the law that establishes security cooperation between the US and Taiwan. But in 2001, Biden wrote a Washington Post opinion article arguing that the law doesn’t require the US to come to Taiwan’s defense. In fact, it left that matter ambiguous, he said.

“The act obliges the president to notify Congress in the event of any threat to the security of Taiwan, and stipulates that the president and Congress shall determine, in accordance with constitutional processes, an appropriate response by the United States,” Biden wrote. “The president should not cede to Taiwan, much less to China, the ability automatically to draw us into a war across the Taiwan Strait.”

Still, a senior Biden administration official told me there are many reasons to believe that America’s support for Taiwan remains ironclad.

“You hear the president consistently talk about how democracies deliver,” the official said. “Taiwan is a leading democracy in the region” and “an example of addressing the pandemic, the Covid crisis, in a way that is consistent with democratic values.”

There’s also an economic imperative: Taiwan is the world’s key manufacturer of semiconductors used in products, from tablets to cars to sex toys, that account for 12 percent of America’s GDP. If China were to usurp Taiwan, Beijing would have a firm grip on that supply chain and thus more influence on the future of the US and global economies.

So would a Biden administration come to Taiwan’s defense? Unsurprisingly, America’s stance on the issue remains ambiguous so far, which is why experts and officials in Taiwan remain on high alert.

“We have to hope for the best and prepare for the worst,” said the Taiwanese source close to the current administration, speaking about the general mood on the island. “That’s our basic philosophy.”

Author: Alex Ward

Read More