Voting rights lawyer Janai Nelson lays out a possible path forward.

It’s too damn hard for too many people to vote in the United States, and that’s no accident.

Voters in predominantly Black and brown neighborhoods often have to wait hours in line to cast a ballot. Lawful voters can be purged from the voting rolls without adequate warning. States enact laws that serve no purpose other than to make it harder to vote — and they often do so with the blessing of the Supreme Court.

Help, however, is potentially on the way. In the first episode of By the People?, a new podcast miniseries that I’m hosting, I spoke with voting rights lawyer Janai Nelson about a pair of ambitious bills that could pass Congress very quickly if Democrats take back the White House and the Senate in November.

These bills offer solutions to a wide range of problems facing American democracy, including gerrymandering, voter purges, and other intentionally efforts to prevent American citizens from casting a ballot.

Nelson, who is associate director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, also walked me through several steps that Americans can take so that their votes are counted in 2020.

An edited transcript of our conversation follows. The full conversation can be heard on By the People.

By the People? is a special podcast miniseries associated with Vox’s podcast The Weeds. You can listen to future episodes of By the People? by subscribing to The Weeds wherever you listen to podcasts, including Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and Stitcher.

Ian Millhiser

So I want to start with a fairly optimistic future. Imagine that it’s January. We have a different president and we have a Congress that is really itching to pass a really strong voting rights bill.

What should be in that new bill?

Janai Nelson

The good thing is we don’t really have to invent a bill out of whole cloth. There are two comprehensive and transformative bills that have already been passed by the House and provide a really excellent starting point to build a new and improved democracy. Those two bills are the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, also known as HR 4, and the For the People Act, known as HR 1.

Ian Millhiser

Yeah, let’s drill down a bit into them. So, one perennial problem we see is that a state will pass something, a law that’s already unconstitutional. Maybe it’s a racial gerrymander, maybe it’s just a way of disenfranchising people — but it could take the courts years to strike that law down. And in those years, the state’s running elections under this law that shouldn’t exist.

How do you prevent that from happening? How do you prevent lawmakers from enacting a law and running several elections under that law, and then maybe enacting something slightly different when the courts get around to striking it down?

Janai Nelson

Yeah, we have seen that happen time and again. Probably one of the most vexing problems for voting rights advocates is the idea that an election can take place under a law that is later found to be discriminatory.

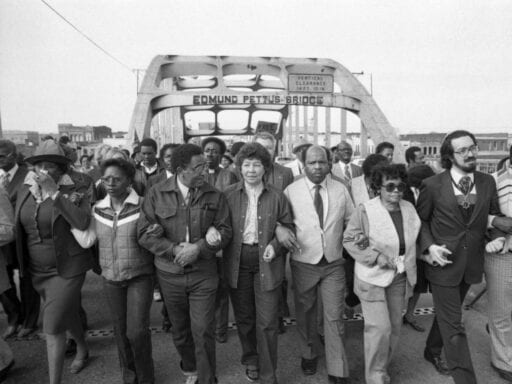

The great thing is that the VRAA, the Voting Rights Advancement Act, which has been named after the late and legendary civil rights hero John Lewis, contains a “preclearance” provision that restores the powerful tool that was in the Voting Rights Act before the Supreme Court disabled it in 2013.

So states like Georgia and Texas and Alabama and Louisiana and many others would have to seek federal approval before they make a voting change. And that’s critical to prevent elections from occurring under laws that should never have been in place in the first place, and that serve to disenfranchise communities and largely Black communities.

Ian Millhiser

The first election I was really old enough to pay attention to was the 2000 election and specifically the 2000 election in Florida. I mean, it was a nightmare. And one of the things that made it a nightmare is that there was this purge list of voters who were kicked off of the voter rolls.

We don’t know how many people were purged who shouldn’t have been purged. But Bush’s margin of victory was about 500 votes. So there’s a decent likelihood that Al Gore would have become president if not for this purge list.

Why is voter registration still a thing that can be used to disenfranchise people? Why is it the case that your right to vote still depends on your name appearing on this registration list? And what does the legislation Congress is considering do to deal with that problem?

Janai Nelson

The 2000 election was the election that really was pivotal for me as well. In fact, it was the very first voting rights case that I ever litigated — to protect Black and Haitian American voters in Florida who had been disenfranchised, some because of the very practice that you mentioned, the voter purge.

So let’s just start with voter purging and then go back to voter registration issues in the 2000 election. There’s something called list maintenance, right? And it’s something that we want to see happen in our states where election officials ensure that the people who are registered to vote are still alive, that they still live in the appropriate jurisdiction, and that they meet all the qualifications that we have for voting. And that’s something that’s perfectly legitimate and fair.

The problem is that many election officials use what should be an innocuous process of just cleaning up the voter rolls to purge people intentionally from the rolls, to actively remove people from the rolls and to target particular groups that they don’t want to vote. We saw that in the 2000 election where at the time [Florida’s] governor instituted a purge process that targeted people with felony convictions.

If you happen to be a member of a community that has a disproportionate number of people with felony convictions, in that case the African American community, also the Latinx community, then you stand a greater likelihood of being kicked off of the rolls as part of that sweep. Not only if you happen to have a felony conviction, but even if you don’t. You may share a name with someone who has a felony conviction. You may be misidentified as someone who has a felony conviction.

Now, if we look at the question of voter registration, why do we need to affirmatively have citizens of this country bear such a disproportionate burden and onus to register? In my mind, it’s such an antiquated process. We’re one of the few democracies that places such a burden on voters to participate in our democracy.

What a growing number of states is doing now is allowing automatic voter registration. So when you turn 18 and you’re a citizen of this country, you can automatically be added to the voter rolls, and different states do it in different ways.

Oregon was the first state to do it in 2015. But since then we have 18 states [and the District of Columbia] that have some form of automatic voter registration, which has increased the voting rolls in many of those states. And there are estimates that suggest that in the first year alone, if we had national automatic voter registration, we might be able to add something like 22-27 million new voters to our voter registration rolls, which could be transformative, especially because it brings a lot of new younger voters into the electorate. And many of them happen to be people of color where we have the largest growing demographic of young people in this country.

Ian Millhiser

Gotcha. And if HR 1 passes, would it require states to have some form of automatic registration?

Janai Nelson

Yes, HR 1 would include nationwide automatic voter registration.

It also includes what is all-important, early voting, two weeks of early voting in every state, which takes the burden off of our election system on a single day, which still exists in some states.

It also marks Election Day as a federal holiday, which again eases the burden on individuals to participate in our democracy by making it a holiday and giving them the time that they need in order to cast their ballots.

And finally, the For the People Act also places some limitations on voter purges, which, again, for the reasons we discussed, is quite important.

Ian Millhiser

So let me switch to a different problem: gerrymandering. Gerrymandering is, I think, a bipartisan problem. But because Republicans happened to have a very good year in 2010, which was the year before the new maps were drawn, they got to do an oversized amount of gerrymandering. And so we’ve seen that in the elections we’ve had for the last 10 years.

What can be done? And what specifically is Congress considering right now to deal with this problem of gerrymandering?

Janai Nelson

Well, it takes us right back to the For the People Act, HR 1, which also deals with partisan gerrymandering.

It institutes nonpartisan commissions to draw electoral districts. And there are roughly 20 states that are already using either bipartisan or nonpartisan commissions to play some role in the redistricting process, which helps to reduce the partisan overreach that occurs, as you noted, from both parties, but has been exacerbated and just exponential in the hands of the Republican Party in recent years.

Ian Millhiser

There’s something that Stacey Abrams, the former Georgia gubernatorial candidate, said that stuck with me, which is that a lot of these laws that are being enacted by state legislatures and upheld by the courts are written to make voter suppression look like “user error.”

It’s not that you were denied the right to vote — it’s that you didn’t bring the right ID. It’s not that you were denied the right to vote — it’s that you didn’t sign your ballot in the right place.

What we see going on now, I think, is different than what happened in Mississippi in the 1950s in that it’s not a wholesale, “Well, I look at the color of your skin so you can’t vote.” It’s an attempt to make it look like it is the voter’s fault.

I guess given that framework, does that mean that voters have more control? Can they take matters into their own hands and make sure that they don’t get trapped by those sorts of things?

Janai Nelson

Voters in this country bear such a significant burden in ensuring that they have an opportunity to participate in our democracy.

That said, the reality is, in this moment, voters must be prepared to vote. There [are measures] that voters can take to do everything within their power to make sure that they are checking their registrations, that their registration is up to date, that they notify election officials if they move, that they know when early voting starts, that they know how they can cast a mail-in ballot.

All of that is information that is readily available to voters if they seek it. It’s unfortunate that they have to seek it. There should be means for voters to receive every possible entry point into our electoral system from state officials. But to the extent that that’s not happening, we’re asking that all voters do whatever it takes to ensure that they can cast a ballot this November.

Ian Millhiser

In the 1980s, the RNC had a scheme where they recruited a bunch of off duty police officers and I believe gave them armbands identifying them as election security with the apparent intent of intimidating Black and brown voters against voting.

And for many years, the RNC was under a court order saying, “Don’t do that.”

The court order has now been dissolved. And this will be the first presidential election without that court order in place. So how worried are you about voter intimidation? And what steps can be taken right now to make sure that voters aren’t scared out of casting their vote?

Janai Nelson

Voter intimidation is as old as this democracy. And the intimidation of Black voters in particular is as old as the 15th Amendment, granting black men the right to vote in 1870.

As you pointed out, there has been something of a control on voter intimidation since the 1980s where you mentioned the off-duty police officers who not only were wearing blue armbands, but they were also armed with service revolvers and they swarmed precincts, many of which were in Black and brown communities in New Jersey and other neighborhoods like that to intimidate them and to deter them from casting their constitutional right to vote.

It took a lawsuit to disband this so-called National Ballot Security Task Force. And what’s interesting is that — I think not so coincidentally now that that consent decree has expired — Trump stated very recently that we are going to have sheriffs, law enforcement, US attorneys, and attorneys general at the polls.

That in and of itself is voter intimidation. To suggest that you have to navigate law enforcement and people who could prosecute you in order to cast a ballot is intimidation on its face.

And just recently, Michigan voters received robocalls misinforming them that voting by mail might expose their personal information to creditors and to law enforcement and even to the CDC for purposes of a forced vaccination.

It’s that type of misinformation that groups like the Legal Defense Fund are combating by telling voters to be discerning, that if they have a question about a voting rule or law or barrier that they hear about, that they check it with a trusted source. Which is why we are part of an election protection network and force that will have people on the ground on Election Day, that will have people available by phone at 866-OUR-VOTE in order to field calls and complaints and to hopefully get relief, and to go to the court, if necessary, to prevent any further intimidation from happening from the polls.

Ian Millhiser

So that number that you just said. 866-OUR-VOTE. If I receive a call telling me if I vote, then there’ll be some terrible consequence, that’s the number that I can call to get credible advice on whether I actually need to worry.

Janai Nelson

That’s right. You can get credible advice on whether that is a legitimate instruction. And it’s also very helpful for us to be able to track what intimidation tactics are being used. And there are many places to go for information if you want to know your polling site, if you know your registration status, there are all sorts of government, as well as civil rights funded sites that can give you that information

Ian Millhiser

Can you name a few of those sites?

Janai Nelson

All voters can go to usa.gov/confirm-voter-registration to check and see if they’re registered to vote. And you can just type in basic information about where you’re located and your name and find out immediately if you are registered to vote.

And the Legal Defense Fund recently launched a microsite that is devoted to voting and voting rights information. It’s a one-stop shop for everything you might want to know about voting rights, including census and redistricting, which is all tied in to this intricate election system that we have. And that voting site is voting.naacpldf.org.

Ian Millhiser

And that’s a good reminder that anyone listening who hasn’t filled out their census form, go do that.

Janai Nelson

Yes, that is critical. Be counted.

Ian Millhiser

So: What is your plan to make sure that your vote is counted?

Janai Nelson

Well, I’m proud to say that I’ve already requested my absentee ballot here in my home state of New York. Early voting here begins October 24 and it ends November 1. And I intend to physically turn in my ballot at a precinct during that early voting period to ensure that it is received and counted.

And frankly, that’s the recommended plan that we have for anyone who plans to vote by mail, that you request your ballot early, if your state requires that you request and not receive it without any demand, and that you physically turn it in to a designated local election drop off or precinct that will take your ballot.

Of course, if you are planning to vote in person, you know, gear up that day and be prepared to face whatever obstacles may come up, including long lines and other issues, ID, if that’s required in your state. And everyone should be reaching out to their networks to make sure that everyone they know is also equally prepared to vote.

And finally, one of the things that the Legal Defense Fund is working on with the More Than A Vote organization that was started by LeBron James is a poll worker recruitment drive. If you have the ability to serve as a poll worker in this upcoming election, please do so. We are facing a shortage of poll workers.

You can go to powerthepolls.org and sign up to find out more about how to become a poll worker in your jurisdiction to help ensure that everyone can cast an equal ballot and receives the assistance that they need in this election.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

The United States is in the middle of one of the most consequential presidential elections of our lifetimes. It’s essential that all Americans are able to access clear, concise information on what the outcome of the election could mean for their lives, and the lives of their families and communities. That is our mission at Vox. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone understand this presidential election: Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Ian Millhiser

Read More