Amy Estes Kavanaugh’s appearance with her husband Monday night shows what #MeToo and 27 years have — and haven’t — changed.

“I know Brett,” Ashley Estes Kavanaugh kept saying.

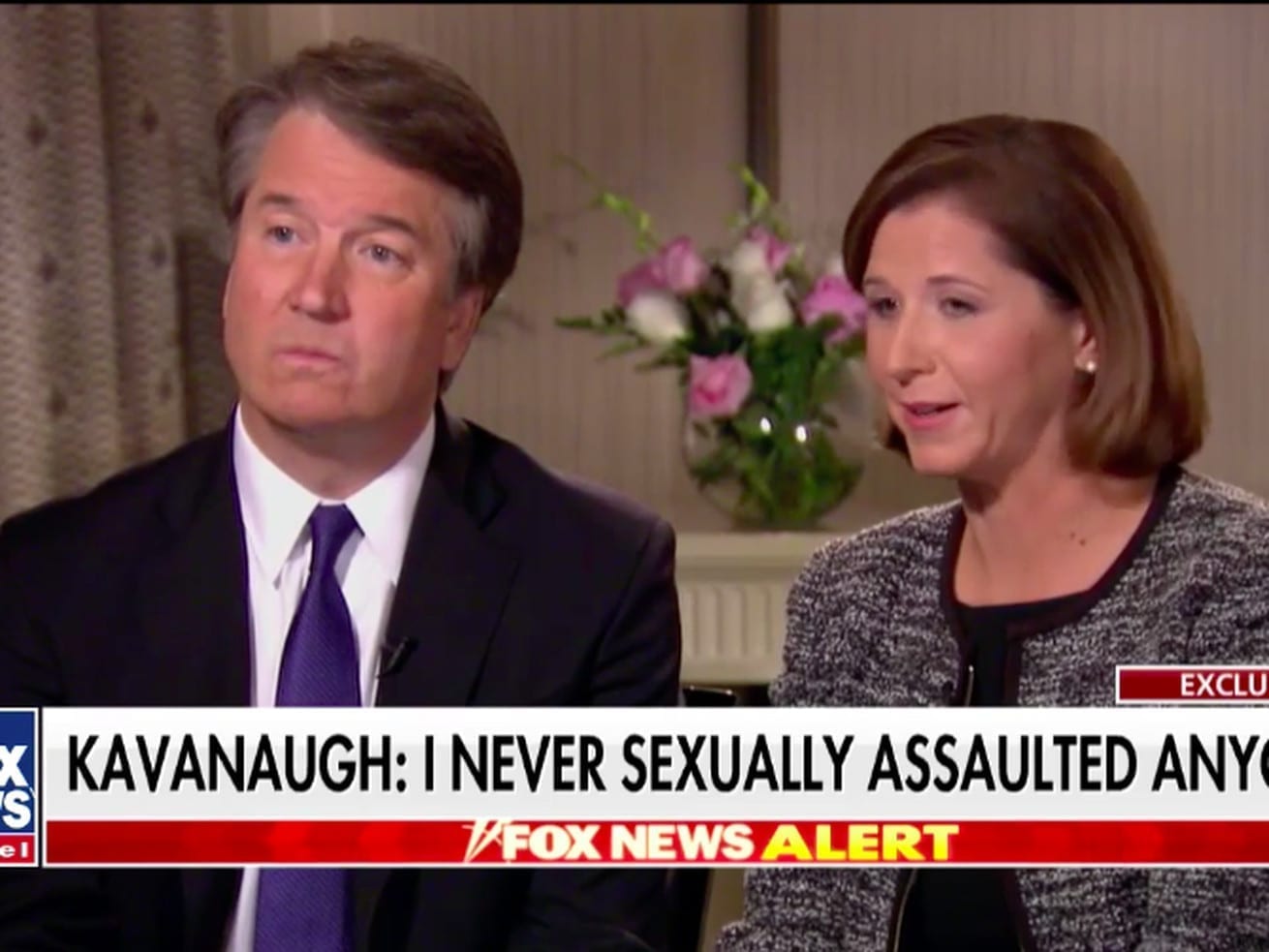

She appeared on Fox News on Monday night beside her husband Brett Kavanaugh, the Supreme Court nominee who has been accused of misconduct by two women: Christine Blasey Ford, who says he sexually assaulted her when the two were in high school, and Deborah Ramirez, who says he thrust his genitals in her face without her consent when they were undergraduates at Yale.

In helping to defend her husband (and his political aspirations) against allegations of sexual misconduct or impropriety, she joined a long line of women, which also includes First Lady Melania Trump and Hillary Clinton. But perhaps the closest comparison is with Virginia Thomas, the wife of Justice Clarence Thomas, who was accused during his confirmation process of sexually harassing Anita Hill. In a People Magazine cover story published just after her husband’s confirmation, Thomas strikes many — though not all — of the same notes as Estes Kavanaugh.

Reading the 1991 story today against Estes Kavanaugh’s Fox appearance shows that though a few things have changed since the advent of #MeToo, one thing has not: when a powerful man is accused of sexual harassment or assault, his wife is still expected to boost his public image as a loving family man. This expectation reveals a misconception #MeToo has yet to change: the idea that a loving family man can’t possibly be guilty of sexual misconduct.

“I know his heart”

Brett Kavanaugh repeated the same statements again and again in the interview, and his wife did the same, using her relatively brief speaking time to repeat several variants on the phrase, “I know Brett.”

“He’s decent, he’s kind, he’s good,” she said at one point. “I know his heart.”

The message: Estes Kavanaugh knows her husband of 14 years better than anyone else, and therefore her version of him is the most trustworthy. That version — decent, kind, good — is someone who could never do the things Ford and Ramirez say Kavanaugh did.

In addition to putting forth this version of her husband, Estes Kavanaugh appealed to the sympathies of anyone who might doubt him by describing their loving family, pained by false allegations.

“It’s very difficult to have these conversations with your children,” she said later, describing the impact of the allegations on their family. But, she added, “they know Brett and they know the truth.”

“Just remember,” she said she told them, “you know your dad.”

Estes Kavanaugh also showed compassion for Ford, refusing to criticize her directly.

“I don’t know what happened to her,” she said. “I feel badly for her family.”

Throughout the interview, Estes Kavanaugh presented herself as a loving spouse who knew her husband’s good character, and who was herself empathetic and good — not someone who could be married to a man guilty of sexual assault. Estes Kavanaugh may indeed believe her husband is innocent, but nonetheless, her appearance followed a pattern.

Virginia Thomas sounded many of the same notes in her People magazine cover story, published in November 1991. Allegations that Thomas had sexually harassed Hill when she worked for him at the Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission had become public during the confirmation process, and Virginia Thomas described to People, as the cover proclaimed, “how we survived.”

Like Estes Kavanaugh, Thomas described her husband as she saw him: a kind and decent man. Thomas said her husband had even encouraged her to report her own experience with sexual harassment.

“He gave me the courage to go forward,” she wrote. “‘It’s not about you,’ he said. ‘It’s about the next woman who comes into a workplace.’”

The Thomases didn’t have children as the Kavanaughs do, but she described getting through the confirmation process with the help of a group of friends who prayed together. “They brought over prayer tapes, and we would read parts of the Bible,” she wrote. “We held hands and prayed. What got us through the next six days was God.”

Thomas described the toll the process had taken on her husband. “Virginia,” she recalled him asking one sleepless night, “why are they trying to destroy me?”

“The Clarence Thomas I had married was nowhere to be found,” she wrote. “He was just debilitated beyond anything I had seen in my life.”

Some things have changed since 1991 — but a lot has stayed the same

Perhaps the biggest difference between Thomas’ account and Estes Kavanaugh’s appearance lies in their treatment of their husbands’ accusers. Thomas did say she thought Hill believed her own testimony about Clarence Thomas: “I believed it was a lie, but she really believed it was true,” she said. However, she was harshly critical of Hill in a way Estes Kavanaugh has not been of Ford or Ramirez.

“What she did was so obviously political,” Thomas wrote. “And what’s scary about her allegations is that they remind me of the movie Fatal Attraction or, in her case, what I call the fatal assistant. In my heart, I always believed she was probably someone in love with my husband and never got what she wanted.”

The Kavanaughs and their team must have known that in the era of #MeToo, it would play poorly to attack Ford or Ramirez, and both avoided doing so.

Other than that, not much has changed in 27 years when it comes to expectations of politicians’ wives. When their husbands are accused of harming other women, they are expected to add credibility to their husbands’ rehabilitation campaigns, talking about home and family and reassuring everyone that a man married to such a nice woman couldn’t possibly have harassed or assaulted someone.

If the allegations against Kavanaugh are true, then Estes Kavanaugh is complicit, to a certain degree, in helping her husband project a wholesome image to the American people. Even so, she is not accused of anything. And like so many wives of high-profile men accused of sexual misconduct, she is faced with an unenviable choice: either break with her partner and the father of her children, or show up as his character witness in the court of public opinion.

Of course, the fact that a person has a nice spouse and a loving marriage has no bearing on whether or not that person has committed sexual misconduct. One of the core revelations of the #MeToo movement has been the sheer prevalence of sexual misconduct — in a survey conducted earlier this year, 81 percent of women and 43 percent of men said they’d been harassed or assaulted at some point in their lives. Given these numbers, it stands to reason that many people have been harassed or assaulted by family men or future family men; people who love their wives and children and pray together with their friends.

It’s a myth that all perpetrators of misconduct are monsters in every aspect of their lives, incapable of love or caring. But, as Estes Kavanaugh’s appearance on Fox showed, it’s a myth that, even in the #MeToo era, is very much alive.

Author: Anna North