The new horror series takes a bevy of fun pop culture tropes on a ride through Jim Crow America.

In the second episode of Lovecraft Country, HBO’s engrossing new pulp horror series, one character, George (Courtney B. Vance), keeps thinking about a book.

The book in question is the 1903 horror fantasy The House on the Borderland, and its plot is eerily similar to George’s present situation: He’s a Black man trapped in a strange mansion along with his friends, presented with various temptations and hallucinogenic visions — including dancing with a woman he knows to be a figment of his imagination. “Do the lovers stay together at the end?” his ghostly date asks of the story. “Yes,” he responds — but only because the giant house they’re in collapses.

There’s an obvious metaphor in the scene about the work Lovecraft Country is trying to do. The show’s story closely follows Matt Ruff’s 2016 novel of the same name, about a Black community in Chicago that becomes entangled with an ominous occult society, all while fighting Jim Crow racism on a scale both everyday and cosmic. Ruff’s novel was an attempt to grapple with the legacy of H.P. Lovecraft’s writing, which is both towering in its influence and teeming with racism. As crafted by showrunner Misha Green, the story, therefore, is both a homage and a repudiation.

It’s a homage in that it gleefully plays with many of the horror tropes its namesake popularized: terrifying otherworldly monsters, esoteric cults, scary American mansions housing obscure spellbooks and dark secrets.

And it’s a repudiation in that it also attempts to wrestle with those tropes and perhaps free them from Lovecraft’s territorial grasp as a loud, vehement, unabashed white supremacist.

It’s helpful to think of Lovecraft Country, then, as akin to a game of Jenga: Its aim isn’t to collapse the house that genre built, but rather to slide a new layer of storytelling on top of century-old bones to find out if the entire structure can still hold. For the most part, it holds very well.

Lovecraft Country’s characters are mythological tricksters. They have to be.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21759877/lovecraft_country3.jpg) HBO

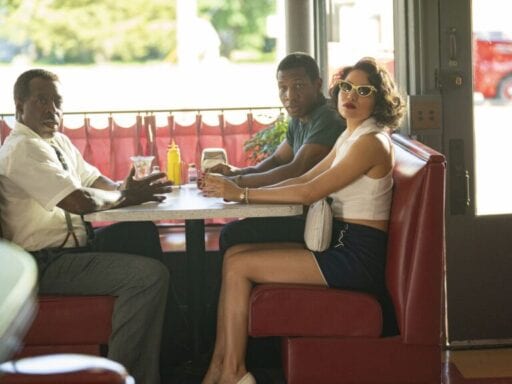

HBOOur story opens as a troubled Korean war veteran named Atticus, a.k.a. Tic (Jonathan Majors), searches for his father Montrose (Michael K. Williams). Though there’s no love lost between Tic and his dad, after Montrose goes missing in the New England wilds that his family calls “Lovecraft country,” Atticus, his uncle George (Vance) and his pal Letitia (Jurnee Smollett) set out on a road trip to search for him. But their plans quickly spiral, and soon they’re confronting monsters in America’s backwoods and small towns. Only some of those monsters are inhuman.

On another TV show, this basic plot might last for a full season, culminating in the group locating Montrose and a dramatic confrontation in a giant creepy mansion. But Lovecraft Country gives you the feeling it’s got no time to waste on such dramatics, so instead the story unfolds very rapidly, largely dealing with the aftermath of that road trip.

The group’s brush with a white supremacist cult has left them entangled in the vague plots of a young witch, Christina (Abbey Lee, whose vibe is very Rory Gilmore meets The Craft), and her creepy pal William (Jordan Patrick Smith, whose vibe is very Draco Malfoy meets Skarsgård). Soon, George’s wife Hippolyta (Aunjanue Ellis), her daughter Diana (Jada Harris), and Lettie’s sister Ruby (Wunmi Mosaku) are all also becoming ensnared in the labyrinthine plots of the cult and its enemies — all while having to deal with much bigger immediate threats like racist neighbors, job discrimination, and violent cops.

Lovecraft Country upfronts the realities of Jim Crow racism for its families. George actually edits a fictional version of a Green Book guide for Black travelers which Hippolyta hopes to join him in writing for one day, and they argue about how to tour the country safely while avoiding sundown towns and racist police. The series reminds us again and again that Black Americans have always had to rely on each other for information, help, and protection in a world that was built to ostracize them.

These are depictions usually reserved for the segregated South in ’50s- and ’60s-era storytelling; though Lovecraft Country is set within that period, most of it takes place in Chicago and Massachusetts, where racist division was very much alive and well but much harder to navigate because it was so often unseen. It’s rare to see the North’s racism get such a harsh excavation, but it’s an effective use of literal racism as horror. Without the South’s more overt legalized racism, the story’s Black characters have to constantly feel their way through every situation: Any town could be a sundown town, any cop could be a white supremacist, and situations that feel stable could become unstable at any moment. It all adds to Lovecraft Country’s permeating layer of dread.

Because Lovecraft Country is airing at a moment when its themes of police brutality and systemic injustice are unfortunately more relevant than they’ve been in years, the hype that has built up around it is the type usually reserved for prestige TV. But while its aims are similar to those of Watchmen, Lovecraft Country is deliberately pulpy. Through the five episodes that HBO has made available for review, the show gambols between various pulp genres like supernatural fantasy à la Lovecraft and Weird Tales, comic books with superpowered heroes and villains, and high tomb-raiding antics out of Edwardian adventure series (think Allan Quatermain or Prisoner of Zenda). Lovecraft Country isn’t just coming for Lovecraft; rather, it’s reclaiming a century of pop literature for Black geeks who never got to be the heroes of those narratives.

Lovecraft, however, remains the central topic of deconstruction. If Lovecraft is obsessed with the omnipresent specters of other races, foreign tongues, and madness, then Lovecraft Country shifts those fears into the point of view of mid-century Black America. Lovecraft’s constant dread of The Other becomes the pervasive threat of whiteness. His terrifying, impenetrable languages become the changing rules and constant hurdles of systemic racism. The strain of avoiding madness becomes the stress of trusting one’s own judgment and experience when reality bends to fit the preferred narrative of white society.

Perhaps most crucially, the characters themselves shift, too. Lovecraft’s heroes were always men, usually erudite and educated, who nevertheless stood in terror of confronting the vast cosmic indifference of the universe and realizing they weren’t at the center of it. The plots of his stories always revolved around their unfolding of the mysteries they found themselves in, and often being driven mad because of it.

None of these concerns apply to our heroes. As Black men and women, they’re under no illusion that the universe was built for them. They’re much more concerned with basic survival. But their self-awareness also gives them an edge that few of Lovecraft’s characters traditionally possess: They know what kind of story they’re in.

Lovecraft Country’s protagonists instantly adapt to the bizarre nature of the supernatural elements around them. Atticus and George are huge fans of weird fiction and horror; they know exactly who and what Lovecraft is and what his stories are about. George’s daughter Diana likewise is a budding superhero artist and writer of comic book sci-fi. They and their families, however reluctantly, know that to survive tropes, you have to subvert them. That allows them to one-up and outwit the dangers that lie in wait for them, whether those dangers come in the form of racist cults, Indiana Jones-style booby traps, or lying cops. They’re tricksters in the truest mythological sense: Their ability to turn the villains’ traps against those villains reveals the traps’ shaky construction.

Lovecraft Country isn’t perfect, but it’s perfectly enjoyable

The show finds its strongest moments when it layers realism atop metaphorical racism to induce a mounting, increasingly surreal two-fold horror. It’s weaker in terms of connecting those moments back to its overarching plot. But that weakness also feels intentional and refreshing — as if the show is also repudiating the pompous dramatics of its silly cult full of white people trying to something something pure bloodlines, something something sorcery, something something existential cosmic terror.

Instead, Lovecraft Country allows itself to be more interested in small stuff, like filming an entire scene mostly underwater because it’s really cool, or devoting an entire episode to routing the racists next door because that’s vital to the main characters’ everyday realities. It’s not quite a pastiche or an anthology show, but it has a similar irreverence for the sanctity of an epic drama. And that irreverence is especially valuable in the way it helps the show present in-your-face, omnipresent racism as part of the real landscape of America.

Lovecraft Country boasts clever, engaging storytelling, but it has less to do with the genres it’s playing with than one might hope. There are literal references galore to the weird fiction writers Lovecraft drew inspiration from and influenced in turn — but although I recognize there’s still plenty of room for supernatural expansion in future episodes, I found myself wishing the vision of the story was a bit broader. One of the biggest absurdities of Lovecraft is that for all he stood in dread of cosmic terror, the most frightening thing he could imagine emanating from that cosmos was basically a really big squid. By the same token, it’s more than a little disappointing that Lovecraft Country — at least so far — hasn’t done more to expand its imagination about what lurks in the beyond.

In its early going, the story remains very faithful to Ruff’s novel, and the encroaching horrors scale up nicely from episode to episode. But the show seems wary of getting too lost in its fantasies, at the risk of downplaying the fact that everyday life for its characters is rarely a daydream.

Particularly odd is Lovecraft Country’s squick about sex and sexuality, which is almost always shown as brutal and unpleasant, if not outright rape, a form of rough power play and violence. On a show where families and community are generally shown as the only safe and intimate harbor, however troubled, it’s a discordant note.

For the most part, however, Lovecraft Country stays honest and engrossing, the kind of show you trust to iron out its own kinks. And it’s more important, ultimately, that the show never lets its indulgence in fantasy overbalance its keen look at racism in America. The show shrewdly leans into a blunt emphasis on the latter that might have felt over-the-top and hamfisted a decade ago.

No matter what, Lovecraft Country’s opening episodes provide an overdue, much-needed perspective shift — a constant reminder that America was always Lovecraft’s country, and many of its citizens are just trying to survive it.

Lovecraft Country debuts Sunday, August 16, at 9 pm on HBO.

Will you become our 20,000th supporter? When the economy took a downturn in the spring and we started asking readers for financial contributions, we weren’t sure how it would go. Today, we’re humbled to say that nearly 20,000 people have chipped in. The reason is both lovely and surprising: Readers told us that they contribute both because they value explanation and because they value that other people can access it, too. We have always believed that explanatory journalism is vital for a functioning democracy. That’s never been more important than today, during a public health crisis, racial justice protests, a recession, and a presidential election. But our distinctive explanatory journalism is expensive, and advertising alone won’t let us keep creating it at the quality and volume this moment requires. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will help keep Vox free for all. Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Aja Romano

Read More