A historian on the unavoidable discomfort around anti-racist education.

If you follow politics at all, you’ve likely encountered phrases and terms such as “critical race theory” or “anti-racism” recently.

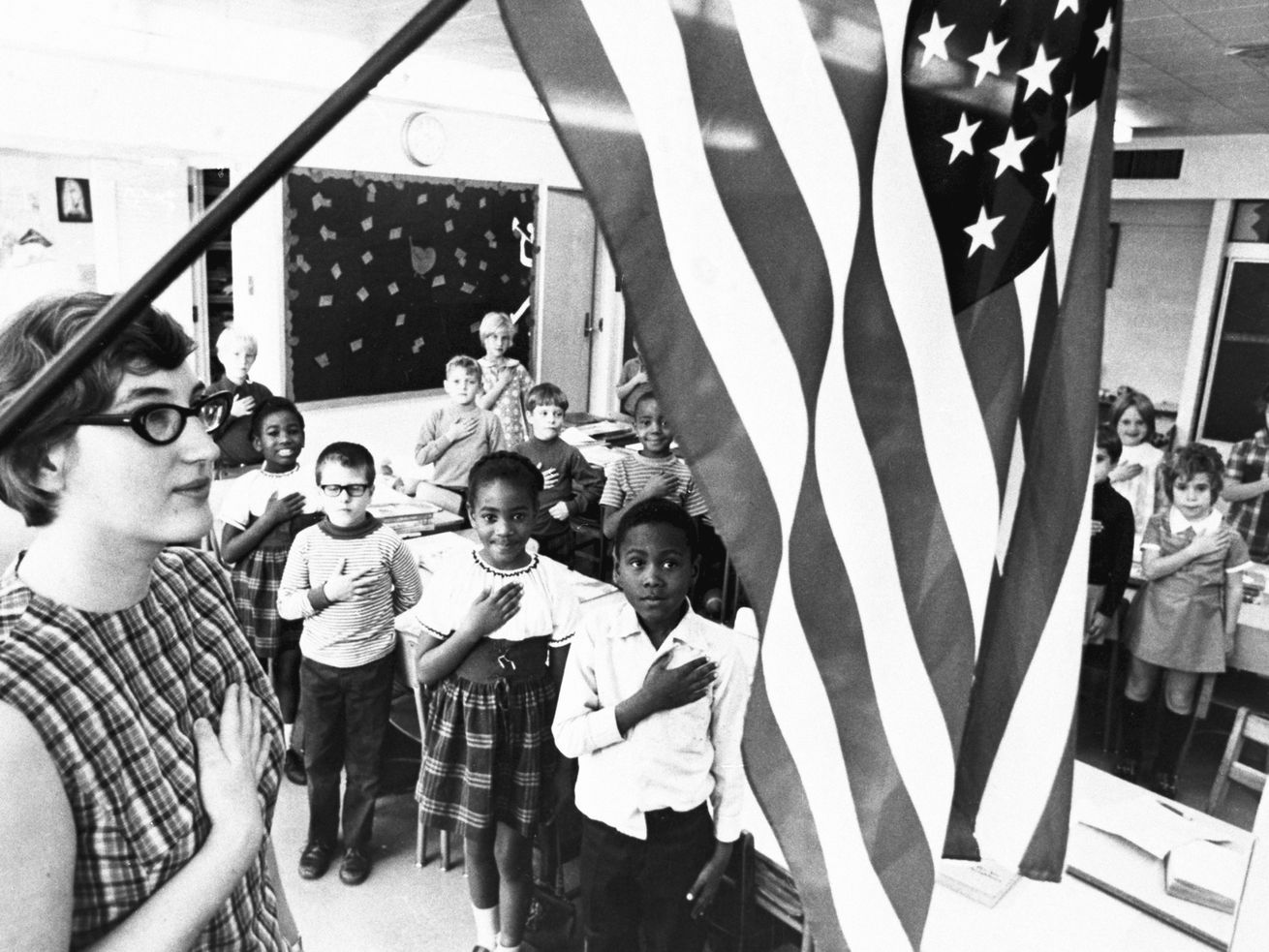

There’s a debate raging over the history and legacy of American racism and how to teach it in schools. The current iteration of this debate (and there have been many) stretches back to 2019, when the New York Times published the 1619 Project, but it evolved into a kind of moral panic in the post-Trump universe, in part because it’s great fodder for right-wing media.

The hysteria over critical race theory, or CRT, has now spilled beyond the confines of Twitter and Fox News. As I explored back in March, conservative state legislatures across the country are seeking to ban CRT from being taught in public schools.

There are lots of angles into this story, and frankly, much of the discourse around it is counterproductive. The main issue is that it’s not clear what these concepts mean, as tends to happen when ideas (à la postmodernism) escape the confines of academia and enter the political and cultural discourse.

Conservatives have appropriated critical race theory as a convenient catchall to describe basically any serious attempt to teach the history of race and racism. It’s now a prop in the never-ending culture war, where caricature and bad faith can muddy the waters. But the intensity of the debate speaks to a very real and difficult question: What’s the best and most productive way to teach the history of racism?

A few weeks ago, I read an essay in the Atlantic by Jarvis R. Givens, a professor of education at Harvard University and the author of Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching. Givens studies the history of Black education in America, focusing on the 19th and 20th centuries.

His essay is mostly about the blind spots in the public discourse around race and education. But in it, he raises a point that seems overlooked: The uproar over CRT isn’t about anti-racist education itself — Black educators in Black schools have practiced that for more than a century. Rather, it’s about the form anti-racism takes in classrooms with white students. Teaching this history to Black students comes with its own complications, but we’re having this discussion because white parents are protesting and entire news outlets are obsessed with it.

So, I reached out to Givens to talk about why this conversation is so hard, how he responds to some of the criticisms of CRT, why he thinks it’s crucial to not get stuck with a single narrative of Black suffering, and why an honest attempt to teach the history of race in America is going to create a lot of unavoidable discomfort.

A transcript of our conversation, lightly edited for length and clarity, follows.

Sean Illing

The term “anti-racism” has become so muddled that a lot of people probably have no idea what it means. How are you using it?

Jarvis R. Givens

It’s about teaching the history of racial inequality and the history of racism, to understand that it’s about more than individual acts of racism.

The idea is that students — and educators — should have a deep awareness of how racist ideas and practices have been fundamental in shaping our modern world. Students need to be able to have these discussions honestly so that new generations of students aren’t just aware of this history, but can also acknowledge and comprehend how our actions can disrupt those historical patterns or reinforce them.

But one thing I tried to do in my piece was remind people that anti-racist teaching isn’t new. We’ve been talking about it in public as though it’s this novel thing, and perhaps it’s because so much of this discussion is about how to teach white students, but for well over a century, Black teachers have been modeling an anti-racist disposition in their pedagogical practices. They recognized how the dreams of their students were at odds with the structural context in which they found themselves. And they had to offer their students ways of thinking about themselves that were life-affirming, despite a society that was physically organized in a way that explicitly told them they were subhuman.

Sean Illing

I don’t want to pass over what you just said about teaching white students, because that does seem to be what this is really about, and you can see it in the debate over “critical race theory.”

You gestured at the criticism I hear the most: that CRT (and, I guess by extension, “anti-racism” education) is built on an assumption that the study of racism has to be anchored to a commitment to undoing the power structure, which is seen as a product of white supremacy. To the extent that’s true, the complaint is that it’s not really an academic discipline or an approach to education — it’s a political ideology.

Jarvis R. Givens

I hear what you’re saying, and I’m not going to argue that there are no clear political commitments on the part of those scholars who gave us CRT. One thing I’d be interested to hear, however, is an alternative approach to teaching the history of America, or the history of anything, quite frankly, that doesn’t have an embedded set of political commitments.

Any approach to framing history is going to have some political commitments baked into the narrative. The choices we make about what to highlight or omit, all of that reflects certain values and biases. It’s just that we often take these for granted when it’s the “preferred” or “dominant” history.

In the end, I don’t see how you can completely remove politics from the work of education or the production of history. I don’t think it’s ever fully possible, and that’s something that isn’t usually acknowledged in these conversations.

Sean Illing

From your perspective, what’s missing from the current discourse around anti-racism education?

Jarvis R. Givens

The best educational models can teach us to recognize injustices, and they can cultivate a commitment to resisting those things, but equally important — and this is something Black educators have done for a long time in their own communities — is modeling other ways of being in the world, other ways of being in relationship to the world.

If you’re striving to create more justice in the world, you can’t do that if you’re only focusing on the things you’re trying to negate. You can’t just be “anti” whatever. You have to have some life-affirming vision that you can hold on to, a vision that’s more meaningful and points us in the direction of a better world. You have to teach people not just to resist injustice but to transcend it. This is what the Black educational models I’ve studied have always done, and it’s lost in so much of the debate about anti-racism and CRT today.

Sean Illing

Why is it so important to move beyond the “anti”?

Jarvis R. Givens

I think it’s important because I don’t want to be stuck with this narrative of Black people as frail and suffering and nothing else. If that’s the image that’s necessary to advance some agenda, we need to rethink some things. I’m not interested in painting this picture of Black folks as only living lives in suffering. If our strategy for seeking justice relies on this image of black folks as damaged and down and out, well, it just falls into a lot of old tropes that we have to be wary of.

Absolutely, there’s injustice. This is a part of the story, part of our story, but Black life is much more expansive than that. It always has been. And so many of our efforts to demand justice have relied on painting an image of Black people as damaged and deficient, and I’m always interested in trying to resist that, and to expand the aperture for how we have these conversations.

Our strategy can’t be just about proving injury. At the same time, the public has to stop denying that harm and violence has been and continues to be done. Both of these things are challenges before us.

Sean Illing

Take an enormous concept like “structural racism,” which is a catchall to describe how contemporary inequalities have their roots in history and institutions. On the one hand, that’s just obviously true. But at the same time — and I think you share this instinct — we don’t want to reduce people to historical props with no agency, and we don’t want to define any oppressed group by the actions of their oppressors.

So, how do you walk that line as an educator?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22645691/Givens_jkt_front.jpg) Harvard University Press

Harvard University PressJarvis R. Givens

Yeah, it’s about taking both structure and agency seriously.

This is one of the things I tried to get at in my book. I was interested in writing against the dominant narrative that we tend to have about Black life and education prior to Brown v. Board. And this is not to diminish the significance of Brown v. Board of Education, but I was interested in thinking outside of the single narrative we’ve inherited: that Brown was necessary because Black people only had schools that were falling apart, with outdated secondhand textbooks, [because] the self-image of Black children was damaged and Black folks had no power.

All of this was baked into the Jim Crow school structure, this racially divided school structure. Proving this, and demonstrating the inherent inequality of Jim Crow, was necessary to achieve the Brown decision.

But to take that as the total narrative of Black educational life is a mistake. Having studied the history, it’s hard for me to paint the story in such a broad stroke. This concern, for me, began with the story of Black teachers that were writing textbooks that challenged the distorted representation of Black life in the dominant curriculum. You have all of these organizations that were created to advocate on behalf of Black educators and students. You have people like Martin Luther King Jr. and John Lewis and Angela Davis, who are the products of these schools and the teaching within them. There was still more to that story than just the narrative of aggressive neglect, of Black schools being starved of resources.

This is all to say, we can hold both things in our minds. We can talk about the violent resistance against Black educational strivings and the intentional underdevelopment of African American schools, but we also have to rigorously account for the things Black folks were doing on a daily basis to make meaningful education possible despite the neglect. And I think that’s necessary if we are to appreciate the suffering and the beauty of Black people’s experience in education, if we are to account for their human striving across generations.

It’s liberating, as a student of history, to realize that so much of it is manufactured. This is essential not just for those of us who write history, but also those of us who are consumers of it. We have to know that the histories presented to us consist of narratives based on decisions people made to represent some aspect of the past. It’s all distortion in some way. It’s important to know that our narratives and origin stories about the past … well, we create them.

One of the best things my high school US history teacher did for me was help me understand that no history is an exhaustive representation of anything. She made me aware of silences. When you allow students to have the agency of knowing that history is not always as authoritative as we tend to imagine, it actually invites them to establish a deeper intellectual relationship with the past. It allows us to think about why certain scholars might have chosen to represent certain aspects of the past in the ways that they did.

Sean Illing

So much of your work focuses on anti-racist education during the Jim Crow era, but we live in a different world today — a flawed world but undoubtedly a better world. How should anti-racist teaching evolve to meet the realities of this moment?

Jarvis R. Givens

This is actually getting at another element that I think is important: A lot of the conversations around anti-racist teaching are directed at white teachers and white students, without actually being named as such. This is obviously very different than talking about how Black educators engaged Black students in the Jim Crow South, or even my own experience growing up in Compton, California, where I attended majority-Black schools with mostly Black teachers.

I’m not going to offer any prescriptive elements about what it means to try and do this work. But I’ll go out on a limb and say this: A fundamental part of being a critical educator, an educator committed to justice and equality, means being committed to reckoning with the history of racial injustice and trying to teach students in a way that supports the development of a critical awareness of that past, which includes acknowledging how that past continues to structure the ways in which we’re in relationship with one another in the present. It means recognizing that many of the institutions we have inherited have very long roots in this history.

There’s a moral imperative for all teachers who choose to face those realities of history and own it in the present. Being an anti-racist teacher in this moment means to honor the depth of human suffering reflected in that history by telling the truth about it. But then again, that’s what anti-racist teaching has always demanded of those educators who chose to teach in a manner that was disruptive to the racial inequality in our society. You can’t look away from it because it’s in every direction you turn.

I do recognize that learning the truth about our histories as different racial groups, and as a country, can be difficult. There’s going to be some level of discomfort, and we have to be real about that. Confronting the history of slavery and Jim Crow has always been difficult for Black people, those who lived through it and their progeny. We don’t experience our ancestors’ suffering in full, but the marks are still there.

Sean Illing

“Discomfort” is probably key here. And in that spirit of keeping it real, let’s just say it: There are a lot of white people in this country, especially white parents, who see all the scary headlines about CRT and the 1619 Project, and they don’t like it. They see “anti-racism” as “anti-white” and it’s … uncomfortable. I don’t know how to teach the truth about America’s past in such a politically fraught environment, but it’s something we’re going to have to figure it out in real time, and it’s going to be messy.

Jarvis R. Givens

To be honest, I don’t really have an answer, because unfortunately, we haven’t had the courage to teach our history honestly. We just haven’t tried it. What we’ve always had instead is a lot of resistance to talking about our past beyond a surface level.

But one thing I do know is that there are some people in this country who never had the luxury of not facing this stuff. And they’ve always encountered a lot of discomfort. It’s not comfortable for Black folks or Native American communities to think about the history of land dispossession or slavery or Jim Crow or lynchings, and how the legacy of these things persist today.

I guess what I’m saying is that certain folks never had the luxury of being comfortable. So now we’re at a place where we’re trying to figure out how to be more intentional in acknowledging our history and its consequences, and that means that discomfort is going to have to be shared in a way it hasn’t been up to this point.

And if we’re going to talk about how to unify the country, the onus can’t just be on the people who are the descendants of enslaved Black people and displaced Native communities, whose forced labor and stolen land were the primary factors of production in building this country. This is something we all have to encounter, and it’s going to be discomforting for everyone.

Author: Sean Illing

Read More