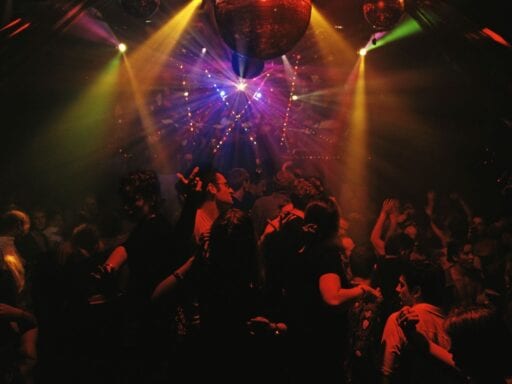

Farewell (for now) to dark rooms, flashing lights, sweaty bodies, and escapism.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15986155/Vox_The_Highlight_Logo_wide.jpg)

Part of the Escape Issue of The Highlight, our home for ambitious stories that explain our world.

Fairly early in the pandemic, when it was becoming clear that the coronavirus would change our lives in myriad ways for the long term, an LA creative studio called Production Club unveiled an invention for our times: a full-body protective suit for clubgoers.

Dubbed the Micrashell, it is a human prophylactic, enveloping wearers’ heads, fingers, and feet. The helmet is the crowning touch, surrounding the face with the sort of soft, clear plastic your grandmother might cover her furniture with. What it lacks in sexiness, it makes up for in utility, allowing wearers to vape and drink through a sealed canister system and even charge their phones.

In the brief optimism of spring, the protective Power Ranger suit seemed premature, silly, and, at worst, a little macabre. Social distancing had made clubgoing unfathomable in the short term, but hanging on to a concert ticket for a few months or imagining a night out — after it all blew over, of course — didn’t seem out of the realm of possibility.

The hazmat suit felt like a downer, a self-fulfilling prophecy that the party was over.

Club people are fickle, always chasing shiny, loud, boozy, and, frequently, regrettable fun to the next new place. I have been to so many music clubs I can’t count them, to raves in cavernous warehouses, to a lounge decorated to look like an apartment, to an illegal venue I was asked to approach from the shadows so the police wouldn’t find it, and to an underground lair outfitted to look remarkably like the inside of a plane, replete with bottle servers dressed as flight attendants. I have even bartended in a club, pouring rail vodka into plastic cups and snatching pleasant bits of conversation with regulars till it was time to hobble home, ears still ringing with EDM, at 5 am.

After all of it, I understand this: Sure, each light flash and drumbeat and bottle price is calculated to excite, to create a mood, but people — ideally lots of them — are what fill venues with energy; without them, clubs are just cold, dark rooms.

Some clubs are known for expensive cover fees, strict dress codes, and racist bouncers. But many others have served historically as gathering grounds for artists and safe havens for gay patrons. They have their own cultures: Some are joyous Black spaces; some, catering to electronic music fans in particular, are places where body positivity thrives.

You can hate them for their velvet ropes and callous door guys and sticky floors and Human Centipede-like throngs. At some point, I submitted to their pleasures, to the anonymity and the ecstatic good time.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21728495/GettyImages_1227844207.jpg) AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesDuring a months-long illness five years ago, I regularly escaped my apartment on Friday nights to visit Washington, DC’s famed Eighteenth Street Lounge, a Euro sort of den of sofas and chandeliers that attracted what I like to call going-out people — industry types, those who thrive on the social interaction, those secure enough to come alone, fist-bump the DJ, and enjoy wherever the night goes. In the dark, among the cash-strapped international aid workers and suits and old house-music heads, nobody seemed to be able to tell that my body had turned on me, or how tired and scared I was. Maybe they noticed and didn’t care. They just wanted to dance, and I am still grateful for it.

Eighteenth Street Lounge closed for the coronavirus shutdown, then announced this summer that it was shuttering for good after 25 years. As the pandemic continues to rack up losses, clubs increasingly seem like yet another casualty, with some wondering if they’ll ever return: In a survey this summer of independent music venue operators and bookers, 90 percent said they would close imminently if no additional aid arrives.

Calling it quits when crowds eventually grow tired of the mojitos and the bass drops is part of the nightclub circle of life. Even Studio 54 lasted just three good years before changing hands, which seems about right for a disco-and-coke-fueled scene of 1970s Manhattan.

But this moment isn’t that. The virus has shown itself to be persistent. It is airborne and able to aerosolize; it has a higher likelihood of transmission indoors and less likelihood with distancing — none of which bodes very well for nightclubs and music clubs, whose very business model depends on squeezing as many bodies as possible into a room.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21729710/GettyImages_1227893291.jpg) Geoffroy Van Der Hasselt/AFP via Getty Images

Geoffroy Van Der Hasselt/AFP via Getty ImagesIn May, South Korea had nearly quashed its outbreak when it identified a new cluster of cases that authorities could trace right back to a Seoul nightclub district, where thousands continued to party. In Spain, too, authorities last month attempted to crack down on a new uptick in cases by shuttering nightclubs again. But in France, nightlife workers and owners have held demonstrations to demand they be allowed to reopen.

These days, my friends who worked in nightlife before the pandemic look hollow-eyed and stoic, like mourners at a funeral; they know there is no foreseeable “phase” of reopening that is safe for them; they know travel restrictions will stifle touring acts; they know that some clientele won’t ever again want to return to a room that’s packed, body to dancing body. Trying to imagine what’s next is like staring into the abyss.

In the interim, some have tried to innovate. In Berlin, a capital of nightclubs, owners and DJs launched a livestream of performances, called United We Stream, that’s reached tens of millions of music fans. Some have tried virtual parties using Zoom. And in France and America, secret dance parties and concerts have sprung up, much to the chagrin of authorities.

And all these months later, the Micracell seems prescient, maybe even a symbol of another industry adapting to a scary new reality. Club culture is fighting; it isn’t yet ready to turn the lights off for good.

Lavanya Ramanathan is the editor of the Highlight. She’s a former features reporter for the Washington Post.

Will you become our 20,000th supporter? When the economy took a downturn in the spring and we started asking readers for financial contributions, we weren’t sure how it would go. Today, we’re humbled to say that nearly 20,000 people have chipped in. The reason is both lovely and surprising: Readers told us that they contribute both because they value explanation and because they value that other people can access it, too. We have always believed that explanatory journalism is vital for a functioning democracy. That’s never been more important than today, during a public health crisis, racial justice protests, a recession, and a presidential election. But our distinctive explanatory journalism is expensive, and advertising alone won’t let us keep creating it at the quality and volume this moment requires. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will help keep Vox free for all. Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Lavanya Ramanathan

Read More