It’s time for the former vice president to make the case for his presidency, not Obama’s.

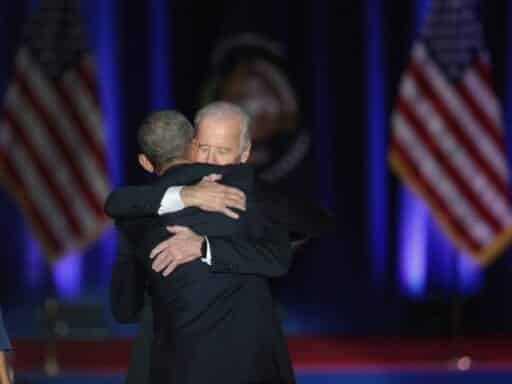

On Thursday, just hours before the third Democratic presidential debate, Joe Biden’s campaign released a new online ad. It was an unusual spot in that it wasn’t about Joe Biden at all. It was about Barack Obama.

Barack Obama was a great president. We don’t say that enough. pic.twitter.com/FLiYpg8jLR

— Joe Biden (@JoeBiden) September 12, 2019

“Barack Obama was a great president,” could be the slogan of Biden’s 2020 presidential campaign. In the first answer Biden gave at the debate, he turned to Sen. Elizabeth Warren and said, “the senator says she’s for Bernie. Well, I’m for Barack.”

To twist Biden’s 2007 line about Rudy Giuliani, it often seems that, for Biden, there are three parts to a sentence: a noun, a verb, and Barack Obama.

Biden served loyally and effectively as Obama’s vice president. When Obama wanted to make sure stimulus money didn’t disappear to fraud, he turned to Biden — “nobody messes with Joe,” he said — and Biden came through. When the White House wanted to avoid the fiscal cliff, it was Biden who closed the deal with Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell. When Obama flubbed the first debate against Mitt Romney, it was Biden who restored the ticket’s mojo by bullying his way past Rep. Paul Ryan. When the Democrats held their 2012 convention, it was Biden’s speech that pulled the highest ratings — beating both Bill Clinton and Obama.

But Joe Biden is not Barack Obama. Some vice presidents are picked for emphasis; Bill Clinton chose Al Gore to drive home his youth and moderation. Others are picked for balance; they’re chosen not for their similarity to the nominee but for their difference. Biden was a balance pick. “I want somebody with gray in his hair,” Obama said. Biden’s presence on the ticket showed that Obama knew what he didn’t know. But that’s why, by definition, Biden doesn’t mirror Obama’s political appeal or personal style and will not mirror Obama’s approach to governance.

Biden is not neatly to the right or left of Obama on foreign or domestic policy, and he diverges dramatically in how he makes decisions, how he understands the basic material of politics, and how he’d run an administration. So in campaigning so explicitly as the inheritor of Obama’s mantle, he obscures both his distinct strengths and his weaknesses, and confuses voters about the kind of president he would be.

It is time for Joe Biden to stop campaigning for Obama’s third term and focus on the case for his first.

Iraq: the definitional difference

Start with foreign policy, where the president has maximum authority and where Biden’s policy roots run deepest.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19197371/GettyImages_74897217.jpg) Scott J. Ferrell/Congressional Quarterly/Getty Images

Scott J. Ferrell/Congressional Quarterly/Getty ImagesBiden and Obama were on opposite sides of the central foreign policy question of the era: whether or not to invade Iraq. Biden voted to give President George W. Bush authorization for the war, and though he was critical of Bush’s preparation and execution, his primary argument wasn’t that Bush was wrong to invade but that he was insufficiently committed to the intervention’s success and hid the true cost from the public. In Promises to Keep, Biden’s 2007 memoir, he wrote:

I still maintain that the costliest mistake the president made was his unwillingness to level with the American people about what would be required to prevail in Iraq. He never seemed willing to ask any but a small percentage to make a real sacrifice to win the war. He didn’t tell them that well over one hundred thousand troops would be needed for many years. He didn’t tell them that the cost could surpass $300 billion. He didn’t tell them that even after paying such a heavy price, success was not assured because no one had ever succeeded before at forcibly remaking a nation, let alone an entire region.

Obama, of course, opposed the Iraq war outright — which was one reason he soundly beat Biden in the 2008 presidential campaign.

Still, it would be too simplistic to say that the sole difference between Obama and Biden on foreign policy was hawkishness.

In the Obama administration, Biden often took the dovish position — driven, perhaps, by a comfort Obama didn’t always show in standing up to the military’s recommendations. Biden argued against expanding American forces in Afghanistan while Obama ultimately committed 30,000 more troops. He recommended against the raid in Pakistan that killed Osama bin Laden. He recommended against the intervention in Libya, a warning that now looks prescient.

In his White House memoir The World as It Is, Ben Rhodes recalls that Biden “repeatedly declar[ed] that experience had taught him that ‘all foreign policy is the extension of personal relationships.’” That’s not how Obama saw foreign policy. But, just as importantly, it’s not how Obama saw domestic policy, either.

The personal is political

Biden’s 2020 campaign thoroughly lionizes Obama, but during his vice presidency, the quiet critique of Obama that thrummed through Biden’s world — and was echoed across Washington — is that Obama didn’t spend enough time schmoozing congressional Republicans, or even congressional Democrats. Perhaps if he spent more time building trust and friendship with congressional leaders, he’d be able to get more done.

In his 2013 White House Correspondents Dinner routine, Obama delivered a funny-because-he-wasn’t-joking riff on these criticisms. “Some folks still don’t think I spend enough time with Congress,” he said. “‘Why don’t you get a drink with Mitch McConnell?’ they ask. Really? Why don’t you get a drink with Mitch McConnell!?”

This is part of the balance Biden brought as vice president. Obama “needed somebody who would deal with Mitch so he wouldn’t have to,” David Axelrod, Obama’s chief strategist, said. Biden’s approach to politics — whether it’s foreign leaders, congressional negotiations, or the Iowa State Fair — is relational. Biden was often deployed to do the in-person work Obama dismissed.

Unlike Obama, Biden is a true creature of the Senate. I’ve profiled Biden’s Senate career at greater length elsewhere so I won’t retell those stories here. Suffice to say that Biden’s political career has been defined by his enthusiasm for Senate relationships, and you can look at that as both an argument for or against his candidacy:

Biden may be the candidate with the best chance of getting legislation through the system as it exists today. If McConnell is the majority leader, if 51 Democrats are still subject to the whims of the filibuster, he might be able to squeeze a bit more out of his former colleagues than his competitors can.

[…] But if you believe that the problems of American politics have passed from the personal to the structural, this is cold comfort. A president with less recollection of how legislating worked in past eras may be freer to imagine the reforms necessary to make it work in the future. Biden is probably the candidate least likely to prioritize ambitious reform of the system. In seeing the humanity of his colleagues so clearly, he has lost sight of the structure that surrounds them; 45 years of personal kindnesses, and a career built in the age of mixed parties, can do a lot to obscure the overarching power of polarization.

This gestures toward the most important political difference between Obama and Biden, one that Biden is strategically obscuring but one that lurks as a vulnerability in his campaign.

Obama railed against the system. Biden represents it.

In 2008, Obama ran as a reformer disgusted by the corruption and polarization paralyzing American politics. Even as president, he radiated a politically useful contempt for the trivialities and politicking of Washington.

Biden represents the system Obama sought to reform. That’s the role Biden initially played on the ticket: Obama was a young guy who turned his inexperience into an asset by distancing himself from a political establishment that had failed Americans, Biden was an older guy who could act as ambassador and guide to that system as necessary.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19197377/461091634.jpg.jpg) Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call

Bill Clark/CQ Roll CallThis is a real vulnerability for Biden. On his own, he will be held responsible for the four decades of policymaking that he participated in. Iraq, the bankruptcy bill, the crime bill, NAFTA, the offshoring of jobs to China — all of it. And the flip side of Biden’s effort to take credit for the Obama administration’s achievements is that he also owns its failures. “You invoke President Obama more than anybody in this campaign,” Cory Booker shot at Biden during the second Democratic debate. “You can’t do it when it’s convenient and then dodge it when it’s not.”

In this respect, Biden is less an inheritor of Obama’s critique of American politics than its target, and Trump, who is skilled at running against the Washington establishment, will take full advantage.

The promise of Biden’s campaign is that, after four years of Trump, the American people will be ready for someone who knows how Washington works and wants to use that knowledge for their benefit. It is, in many ways, the reverse of Obama’s initial promise — which perhaps makes Biden right for this moment but makes him fundamentally different from Obama in both his appeal and his vulnerabilities. And it’s a big bet for Democrats to make: In recent presidential elections, Americans have repeatedly chosen the outsider, not the insider, candidate.

For that reason, Biden needs to make the argument for his style of politics clearly and explicitly. And, at times, he has. “Some of these people are saying. ‘Biden just doesn’t get it,’” Biden said in his announcement speech. “You can’t work with Republicans anymore. That’s not the way it works anymore. Well, folks, I’m going to say something outrageous. I know how to make government work — not because I’ve talked or tweeted about it, but because I’ve done it. I’ve worked across the aisle to reach consensus. To help make government work in the past. I can do that again with your help.”

The problem Biden faces in rooting himself so thoroughly in the Obama administration is that government often didn’t work in that era. After retaking the House in 2010, Republicans blocked Obama’s agenda and Washington ground into gridlock and recrimination. When Hillary Clinton ran in 2016 as the continuation of the Obama era, she lost to Donald Trump. It’s possible that four years of Trump have caused voters to rethink that preference, but it’s a thin argument.

Biden needs to make the case that he can move beyond the frustrations of Obama’s second term, that his approach will build on what came before rather than simply return to it. This is an argument that my reporting suggests Biden believes, but he spends so much of his energy in the debates extolling Obama’s approach to politics that he’s left himself little space to define his own.

This is why Biden needs to run as his own man rather than as Obama’s. He is not Obama, and he will not be able to pursue an Obama-like campaign or run an Obama-like administration. He will have his own ideas, his own staff, his own ways of deciding difficult issues and navigating the byways of American politics. What needs to be established is the case for Joe Biden, not the case for Barack Obama.

Obama may have been a great president, but he’s not running. Biden is.

Author: Ezra Klein

Read More