A classic of children’s literature captures the warmth and comfort of Thanksgiving.

Thanksgiving is different this year. And it can be helpful, when holidays don’t feel quite right, to return to the holidays of children’s literature, where everything is codified and comfortably familiar.

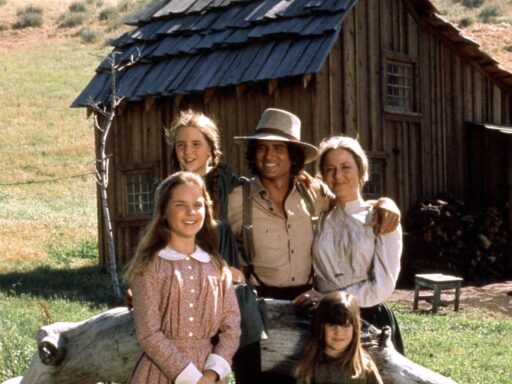

You might think that Laura Ingalls Wilder’s immortal Little House books would suit our purposes perfectly. But in the entire nine-volume saga, there are only two Thanksgiving scenes.

That seems wrong. The Little House books are obsessed with food and patriotism, and what is Thanksgiving but our national excuse to indulge in both in equal measure? These books are designed to codify the myth of the self-sufficient pioneers, pulling themselves up by their bootstraps and living off the fat of the land. They take an almost pornographic pleasure in describing butter-churning and hog-slaughtering and corn-harvesting. Thanksgiving should be entirely up their alley.

But the Little House books are also about deprivation and hunger, about how for the Ingalls family luxuries are always scarce, and even necessities aren’t exactly abundant. So while Wilder always makes room in her narrative for a Christmas scene or two, the celebration is usually pointedly minimal, the better to set off the Ingallses’ austere morality. Laura and Mary are delighted by tiny Christmas cakes made with pristine white sugar and white flour instead of the everyday brown; they dutifully ask Pa to purchase workhorses for Christmas instead of spending money on buying them presents.

There simply isn’t room, in these books about survivalism, for more than one pious feast day a year. So the two Thanksgiving scenes that we do get serve very specific purposes.

The first one, in On the Banks of Plum Creek, serves as the calm before the storm: The Ingallses feast on stewed goose with dumplings and give thanks for the bounty of their land, little knowing that a biblical plague of grasshoppers is about to descend upon them and destroy their farm. Christmas that year is a disaster. Thanksgiving is the only reprieve they have.

The second Thanksgiving comes in Little Town on the Prairie, toward the end of the series, when the Ingalls family has settled down in the slowly developing town of De Smet, South Dakota. For the first time, they have neighbors living close by; they have an infrastructure to supply them with such perks as surplus food and coal and medical care.

For Laura, the town is equal parts exciting and suffocating: she longs to travel further west, to be utterly isolated on the prairie, but she also loves the companionship and sociability of the town, and she knows that her delicate invalid sisters (blind Mary, undernourished Carrie, and baby Grace) need its riches to survive.

So when Thanksgiving arrives in this book, it’s not just a family affair. It’s a town event, a New England dinner hosted by the church’s Ladies’ Aid Society. It’s a big, bustling celebration, packed with people and food, at once lavish and exciting and overwhelming:

Laura stood stock-still for an instant. Even Pa and Ma almost halted, though they were too grown-up to show surprise. A grown-up person must never let feeling be shown by voice or manner. So Laura only looked, and gently hushed Grace, though she was as excited and overwhelmed as Carrie was.

In the very center of one table a pig was standing, roasted brown, and holding in its mouth a beautiful red apple.

In all their lives, Laura and Carrie had never seen so much food. Those tables were loaded. There were heaped dishes of mashed potatoes and of mashed turnips, and of mashed yellow squash, all dribbling melted butter down their sides from little hollows in their peaks. There were large bowls of dried corn, soaked soft again and cooked with cream. There were plates piled high with golden squares of corn bread and slices of white bread and of brown, nutty-tasting graham bread. There were cucumber pickles and beet pickles and green tomato pickles, and glass bowls on tall glass stems were full of red tomato preserves and wild-chokecherry jelly. On each table was a long, wide, deep pan of chicken pie, with steam rising through the slits in its flaky crust.

Most marvelous of all was the pig. It stood so life-like, propped up by short sticks, above a great pan filled with baked apples. It smelled so good. Better than any smell of any other food was that rich, oily, brown smell of roasted pork, that Laura had not smelled for so long.

Laura, overwhelmed by all the people and all the rich food around her, does not get to dive into that roasted pig herself. Instead, she stays busy washing dishes throughout the entire dinner, like a dutiful and responsible young lady. But try as she might, she can’t stop herself from thinking about that pig. She’s only able to eat at the end of the night, when “a pile of bones lay where the pig had been,” although Laura notes optimistically that “plenty of meat remained on them.”

That onslaught of sensory detail; the immense, lavish display of table after table of food after so many passages full of deprivation and misery; the longing for luxury that is so intense as to feel almost illicit; the ostentatious choice to turn away from physical pleasures to do one’s duty: Those are the conflicting strains that run through all of the Little House books, that grant them their visceral emotional force.

And here, they argue that community is necessary to Thanksgiving. In the Little House books, Christmas happens every year, but Thanksgiving only appears in all its table-groaning glory when the Ingalls family has become part of a town. Thanksgiving in Little Town on the Prairie means crowds that are both exciting and suffocating; it means piles of food and piles of dirty dishes that have to be cleaned. And most importantly, it means feasting after famine, luxuriating in food after years with almost nothing — even if you’re last in line to eat.

In 2020, Thanksgiving for so many of us will be a Thanksgiving without crowds and without community, because that is what we have to do in order to preserve our communities, so that they are here for us to celebrate with next year. But Little Town on the Prairie is a reminder of what’s waiting for us after we make it through this dark year.

This is the grasshopper year, the year when everything goes wrong. This is the year that time passes, and on the other side of it will be our best Thanksgiving yet.

Author: Constance Grady

Read More