How Trump’s coronavirus response is hurting him in the polls.

In early April, President Donald Trump’s job approval reached 46 percent in FiveThirtyEight’s poll aggregator — its highest level since January 25, 2017, and a 6-point increase since early November. It has since drifted back down to 43 percent. If Trump received any bump from his handling of the coronavirus outbreak, it was unusually small and short-lived.

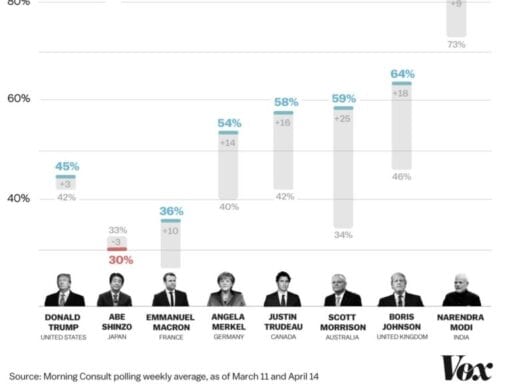

International comparison is useful here. Leaders in most peer countries saw 10- to 20-point increases in their Morning Consult polling numbers by mid-April compared to a month earlier, when the World Health Organization declared Covid-19 a pandemic. Canada’s Justin Trudeau has seen a 16-point bump; Scott Morrison of Australia a 25-point increase; even the largely unpopular French Prime Minister Emmanuel Macron has seen his job approval rise 10 points.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19935658/world_leader_ratings_1_high_low.jpg)

These across-the-board increases are examples of what political scientists call the “rally-round-the-flag effect,” a term used to describe the temporary boost in popularity that leaders get during a crisis. But it’s not only heads of state who have seen their citizens rally around them — Democratic and Republican state governors across the US have seen big increases in popularity as well, upward of 15 points in various polls, compared to a Morning Consult baseline at the end of 2019.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19935493/governor_approval_rating_high_low.jpg)

This raises an important question: Why has Trump’s approval bump been so small relative to most other leaders at home and abroad?

One theory is that the Trump administration’s late and botched response to the coronavirus has dragged down the president’s popularity. There’s some data behind this intuition: According to two recent polls, 65 percent of Americans say either that Trump did not take Covid-19 “seriously enough at the beginning” or that he was “too slow to take major steps” to address the situation.

But plenty of other leaders have had huge popularity boosts despite their own flailing responses. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s overall favorability is up 27 points despite criticism for his hesitance to push for more drastic measures early in the crisis. The UK’s Boris Johnson, who came under fire for his government’s infamous “herd immunity” strategy in mid-March, has seen an 18-point bump. Even Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, whose initial response has been viewed as a cautionary tale of what other countries should avoid, saw his administration’s approval rating shoot up from 27 to 71 percent.

As my colleague Matt Yglesias points out, “If anything, European data seems to suggest bigger bounces for leaders with less effective responses.” (One major unknown is Spain, for which there is currently no good polling data.)

However, it does seem to matter how long that ineffectiveness lasts. A common thread among Cuomo, Johnson, and Conte: Despite fumbling their initial responses to Covid-19, they quickly changed course and began implementing clear, focused public health measures informed by scientific consensus. Voters might forgive an initial display of incompetence in the face of a novel threat if their leaders quickly adapt and steer the ship in the right direction.

Trump, it seems, has not earned much forgiveness. After denying the severity of the outbreak well into March, Trump looked as though he was beginning to change course. But then he reversed once again. He began saying that the cure of social distancing was “worse than the problem itself,” claiming the country would reopen by Easter, and endorsing unproven (and possibly dangerous) therapeutics. Last week, he even suggested that injecting people with bleach might be a potential treatment (seemingly prompting hundreds of calls to poison centers seeking guidance).

“The disinfectant, where it knocks it out in a minute, and is there a way we can do something like that by injection inside, or almost a cleaning. It gets in the lungs” — Trump seems to suggests that injecting disinfectant inside people could be a treatment for the coronavirus pic.twitter.com/amis9Rphsm

— Aaron Rupar (@atrupar) April 23, 2020

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis offers a useful point of comparison here. As the Tampa Bay Times reports, DeSantis has pushed unproven coronavirus therapeutics, dismissed advice from health experts, spread misinformation, refused to schedule regular public briefings, and shut down his state unusually late. So far, voters have treated him the same way they’ve treated Trump: DeSantis has also been denied a pandemic bounce, with different surveys ranging from a 5-point drop to a 1-point bump in his job approval.

“I can’t tell you what will happen in November,” Vanderbilt political scientist John Sides says. “What I can tell you is that Trump’s failure to get a large approval bump means that Republicans have left a lot on the table. That’s probably going to hurt them.”

Trump’s fumbling response has been compounded by divisive rhetoric

Behind the polling bumps that leaders get in times of crisis is the support of political elites who normally oppose them. During a war or after a terrorist attack, opposition party leaders will often join with the president or prime minister in a show of national unity — and that’s a signal to their voters to get in line, too.

We live in a polarized political era, but structural polarization is probably not the primary factor driving down Trump’s approval bump. After all, governors in deeply divided purple states — like Gretchen Whitmer in Michigan, Tony Evers in Wisconsin, Roy Cooper in North Carolina, and Mike DeWine in Ohio — have all seen large surges in popularity.

“Governors do tend to be seen through less partisan lenses than presidents, which could explain some of the difference,” said Patrick Murray, the director of the Monmouth Polling Institute. “However, the amount of movement [in approval ratings] we’re seeing for governors no matter what state they are in suggests the lack of movement for Trump is unique to him.”

What’s been striking about Trump’s political response to the coronavirus is how little he has done to try to foster any sort of unity. Since the coronavirus outbreak, Trump has called Nancy Pelosi a “sick puppy” and lashed out at Chuck Schumer. He’s initiated Twitter spats with state governors. He’s blamed former President Obama for the testing failures and shortage of medical supplies. He’s insulted reporters who dare to ask him basic questions at press briefings as “third rate,” “horrid,” and “a disgrace.” He’s called Whitmer “Half Whitmer” and said she’s “way in over her head.”

I love Michigan, one of the reasons we are doing such a GREAT job for them during this horrible Pandemic. Yet your Governor, Gretchen “Half” Whitmer is way in over her head, she doesn’t have a clue. Likes blaming everyone for her own ineptitude! #MAGA

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 28, 2020

LIBERATE VIRGINIA, and save your great 2nd Amendment. It is under siege!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 17, 2020

After the passage of the bipartisan CARES Act, Trump broke with both traditional and accepted political best practice and only invited Republican leaders to the signing ceremony. Given a chance to visually take credit for bringing both sides together to deliver much-needed help to unemployed Americans and struggling businesses, he chose to construct a visual that omitted any Democratic backing for the bill he was signing.

“The vast majority of what is causing the lack of movement in Trump’s approval rating comes down to who Donald Trump is,” Murray told me. “You can’t imagine any other person who could have gotten up day after day playing so strongly to his base or criticizing in schoolyard terms other officials around the country.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19922376/1208433580.jpg.jpg) Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images

Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty ImagesThere’s been a lot of focus on how the Trump administration was technically and strategically unprepared for this crisis — and that’s true. But there’s also a way in which Trump himself was not temperamentally or ideologically prepared for it either. Trump built his political career atop fracture, conflict, and polarization. But he’s just collided with a crisis that demands solidarity, unity, and mutuality.

“If there’s any president I would expect no rally effect for, it would be Trump,” said Adam Berinsky, a political scientist at MIT whose research focuses on public opinion during wartime. “I would bet a considerable amount of money that if we had Marco Rubio as president, things would look differently.”

Looking toward November

Economic collapse tends to be a disaster for incumbent presidents, especially if it occurs in an election year — and we are witnessing a pace of economic disintegration so staggering that only the Great Depression can compare.

There is some evidence that the link between the economy and presidential approval has become “increasingly untethered,” as a study by several political scientists put it last year. But that’s the case in ordinary times — and what we are living through is anything but ordinary.

“When we’re in normal economic times, it’s easy for partisans to engage in motivated reasoning about political and economic performance,” Ellen Key, a political scientist at Appalachian State University and one of the authors of the aforementioned study, said in an email. “However … when the economy is performing unambiguously well or unambiguously poorly, it’s a lot harder to engage in these biased evaluations.”

Experts forecast that GDP could fall 30, 40, even 50 percent this quarter, any of which would be unprecedented in the history of the measurement. In a conversation with my colleague Ezra Klein, Scott Gottlieb, the former Food and Drug Administration commissioner, made it clear that even if we do everything right — from scaling up mass testing to surging health care capacity and more — the best we can hope for is an “80 percent economy” until a vaccine emerges. That sounds like a hopeful number, but it still represents an economic downfall of Great Depression-like proportions — the political implications of which could be devastating.

The fact that Trump has received such a small bump at the outset of this crisis — when approval ratings tend to rise most rapidly — will make a later recovery, amid a worse economy, difficult.

“This doesn’t mean Trump will for sure lose” in November, Sides says. “But we will be able to say he had an opportunity to change a historically low approval rating — and he failed to do that.”

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Roge Karma

Read More