And the rest of the week’s best writing on books and related subjects.

Welcome to Vox’s weekly book link roundup, a curated selection of the internet’s best writing on books and related subjects.

Well, here we are. We made it through another week. Time has ceased to have meaning, but technically speaking, it is a Saturday. Time has passed, time moves forward, books remain here with us.

And the brand new Vox Book Club kicked off our first discussion this week! We’re reading the new N.K. Jemisin novel The City We Became, truly a Now More Than Ever book. Come and read and hang out with us in the comments section all week long.

Now, in the meantime, let’s see what there is to read online about books this week. Here is the web’s best writing on books and related subjects for the week of April 5, 2020.

- The Guardian looks into erotica trends in the coronavirus era:

Well, there is Covid-69: An Erotic Coronavirus Quarantine Story by J Andrews. And Sex During the Coronavirus Pandemic (tagline: “They could lock down her country, but never her heart”). And FFM Lockdown. And The Physical Manifestation of Washing My Hands Gets Me Off, in which a woman begins a lesbian affair with the physical manifestation of the concept of hand-washing.

- Also at the Guardian, Katy Young judges the bookshelves of celebrities.

- ProPublica investigates the white supremacists operating through Amazon’s self-publishing arm:

About 200 of the 1,500 books recommended by the Colchester Collection, an online reading room run by and for white nationalists, were self-published through Amazon. And new KDP acolytes are born every day: Members of fringe groups on 4chan, Discord and Telegram regularly tout the platform’s convenience, according to our analysis of thousands of conversations on those message boards. There are “literally zero hoops,” one user in 4chan’s /pol/ forum told another in 2015. “Just sign up for Kindle Direct Publishing and publish away. It’s shocking how simple it is, actually.” Even Breivik, at the start of the 1,500-page manifesto that accompanied his terrorist attacks, suggested that his followers use KDP’s paperback service, among others, to publicize his message.

- At Believer Mag, Lorraine Boissoneault delves into the ways speakers of endangered languages are fighting to preserve them:

The challenge of rebuilding a language that’s been suppressed for decades is not simple. It is something of a Hydra, but its ravenous heads must be nourished rather than massacred. First, you have to assess the state of things—how many people speak the language, and at what level. If any speakers remain, you rush to record their words. Next comes the work of exhaling those words back into the world—training new teachers to educate young students, producing lesson plans, crafting multimedia resources, like books or smartphone apps. Then you have to enlist linguists to provide grammatical analyses and produce dictionaries. And if no one speaks the language anymore, you must excavate archival materials to provide the foundation for the language’s renewal. All of this work must be done by individuals who often have little training or financial support.

- At the New Yorker, David Remnick talks to Lawrence Wright about his forthcoming pandemic novel:

Does it feel a little weird to have a novel coming out about a pandemic in the midst of one?

You have no idea.

Tell me.

In some ways, I have to admit, I’m kind of proud that I imagined things that, in real life, seem to be coming into existence. On the other hand, I feel embarrassed to have written this and have it come out. I don’t know what the world’s going to be like when it’s finally published, because this disease gallops along so much.

- The New Yorker has been compiling responses to the pandemic from novelists. Here’s Bryan Washington on grocery shopping:

In Houston, preparation is tied to the city’s topography. Harris County’s share of upper- and lowercase storms in the past few decades has produced a reliable equation: if there’s even a whiff of an emergency on the horizon, our grocery stores begin to fill. The shoppers tend to move in waves: there’s your First Wave, folks who just triple up on everything, because they’re older or they’re preppers or they’re refugees, or maybe they’ve just seen some shit in their lifetimes. Then there’s the Second Wave, folks who surface after the plausibility of an emergency coalesces (more folks of color). There’s the Third Wave, once the emergency becomes imminent (the stores get crowded), and then the Fourth Wave, after city officials legitimatize the Bad Thing. That’s when you end up texting in line, hunched over your cart for hours.

- At the New York Times, two theater critics suggest novels to read while you can’t go to the theater:

In this period of suspension, novels set in the theater are portals into a realm that in real life has temporarily gone dark. Immersive by nature, staged inside our minds, they can sit us down in a buzzing audience or slip us into a darkened wing, sneak us inside a tense rehearsal room or pop us onto a bar stool at an after-party.

- I reread Emma last week and found it to be exactly what I needed. At Electric Lit, Janice Hadlow looks at why Jane Austen is so compelling in hard times:

I don’t think we continue to turn to Austen because, unlike us, she was protected from the capricious miseries of life. On the contrary, I’d argue that her power to connect with us in hard times arises not because her retired life shielded her from grief, pain, and fear—but because she knew very well what it was like to feel vulnerable, exposed, and anxious about the well-being of those she cared about.

I think it’s this experience that gives Austen’s writing its muscularity and strength. We wouldn’t return to her again and again if all she had to offer us was an agreeable candy-colored fantasy. There’s a toughness in Austen that tempers everything she writes, even her lightest and brightest moments. It isn’t always pretty, but it’s an inescapable part of who she is. It offers an altogether more bracing prescription of how to respond to terrible events—and is, I think, a product of her constant exposure to a steady stream of human tragedies.

- At LitHub, Emily Temple has put together a very good list of very long novels.

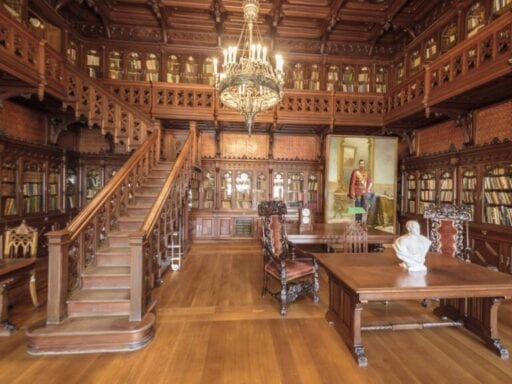

- Also at LitHub, Sara Martin explains how she fell in love with libraries:

Learning the history of this institution has made me realize that libraries actually want to change all the time. People who work for libraries are not interested in insisting on a system that isn’t reaching anyone; they think of libraries as living documents. Libraries change as the public demonstrates what is not working for them and expresses desires for access to new literacies. This is the ultimate goal of the library: to keep evaluating and redirecting in pursuit of knowledge.

- At the Paris Review Daily, Drew Bratcher reads Montaigne’s plague essays:

“Of Experience” is about how to live when life itself comes under attack. Because life as we’ve known it is on hold at the moment, because sickness and confusion are everywhere, and because one of the things books are good for is reminding us that we aren’t alone in history or consciousness, reading “Of Experience” right now feels like an analogue to experience; not a cold study of a distant artist’s late style so much as wisdom lit for wary souls unresigned, as of yet, to world-weariness.

And here’s the week in books at Vox:

- Vox Book Club, The City We Became, Week 1: New York City is born. What happens next?

- Ask a Book Critic: What should I read when I can’t get any work done?

- Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

As always, you can keep up with all our books coverage by visiting vox.com/books. Happy reading!

Author: Constance Grady

Read More