The stability that comes with a particular food or device can be disrupted if it’s lost, broken, or discontinued. That’s where the internet comes in.

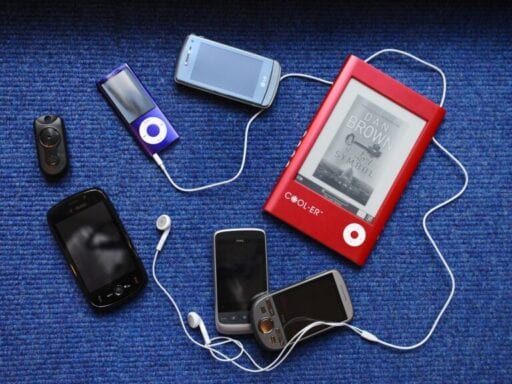

After 12 years of loyal and increasingly glitchy service, my beloved sixth-generation black 80GB iPod Classic finally died this summer, taking a small chunk of my ability to function in the outside world with it. I’m autistic, and the media player had become a mix of a sensory regulation aid and security blanket for me. Smoothing my thumb around the click wheel was one of my favorite stims (a repetitive movement that many autistic people can use to help self-regulate). Making and listening to playlists — generally one to three carefully selected songs on repeat — helped me drown out other potentially overwhelming noises when I was out in public. And it gave me something to focus on when I was struggling with anxiety or dissociation.

I’ve been a bit lost since the iPod’s demise, but the only thing that upsets me more than not having it is the idea of replacing it with anything other than the same iPod. Just thinking about having to adjust to a media player that operates and fits in my hand in a slightly different manner — or even having to look at it in a different color — viscerally upsets me in a way I can’t quite articulate. So I’ve been spending a lot of time on eBay, looking at the refurbished sixth-generation black 80GB iPod Classics that are available and trying to determine which refurbisher I should order from. And how many I should get.

Autistic people can have an aversion to change and disruption. “Reality to an autistic person is a confusing, interacting mass of events, people, places, sounds and sights,” autistic writer and researcher Therese Jolliffe explained in “Autism: A personal account.” “There seem to be no clear boundaries, order or meaning to anything. A large part of my life is spent trying to work out the pattern behind everything. Set routines, times, particular routes and rituals all help to get order into an unbearably chaotic life. Trying to keep everything the same reduces some of the terrible fear.”

This effort to establish some stability is often reflected in the way we use consumer goods. We might only wear particular pieces of clothing or only eat a limited number of foods — sometimes only when they come in a specific package. We tend to use the same items over and over again until they fall apart, or we lose them.

If there’s a disruption in these patterns, the fallout can range from discomfort to potentially life-threatening dietary changes. The market is its own confusing, interacting mass of events, fast fashion, trends, rebranding, and planned obsolescence, though. Which means that trying to procure the goods we want and/or need becomes yet another thing that autistic people do atypically.

In their most pressing form, these quests can go global, sometimes with heartening results. This past July, Twitter mobilized to help replace a Next brand dress for an autistic girl who wouldn’t wear anything else. Other girls who owned the tunic and the British clothing retailer itself sent backups in multiple sizes after a family friend’s plea went viral. In 2016, Tommee Tippee made 500 blue sippy cups for a 14-year-old autistic boy who only drank from its recently discontinued model when his father ran out of replacements and turned to the internet for help.

STOP THE CLOCK! Yesterday I put a tweet out asking people if they had this Next dress from 3 years ago because my friend @mousmakes has a daughter with autism who can only wear that dress. I asked people not to judge because in the scheme of things it doesn’t matter does it. 1/10 pic.twitter.com/AbqmR4zd6z

— Deborah Price (@deborahprice1) July 7, 2019

But the practice is far more widespread and varied than the occasional human interest story. Most autistic people, and our supportive family members and friends, have at least something that makes our lives more manageable. And we also have some sort of stash, hack, or search network to sustain our access to it.

Carole Ann Littlehales has been ordering the same few clothing and food items in bulk for her autistic son Edward, who is now in college, since he was a child. He’s relaxed his wardrobe restrictions somewhat since turning 18, but his diet remains rigid. She reports that he eats an increasingly limited diet of specific brands, including Nesquik chocolate powder, Jaffa Cakes, two flavors of Capri Sun, and Laughing Cow cheese spread. “His only concession to something different is that he will eat some chips from our local Chinese takeaway, but he only ever eats these on Saturdays,” Littlehales says.

In response, her grocery shopping habits have become vigilant — and creative. “I stockpile everything as if I can’t source them in the shops, and he will not have alternatives. I can’t substitute ASDA cream crackers with other brands as the ‘pattern is different.’ Our local shops were not selling Laughing Cow anymore at one point. I wrote to Laughing Cow in France and they sent, via courier, a refrigerated package with 48 boxes of cheese in it.”

Beyond his basic needs, Littlehales also does her best to facilitate Edward’s lifelong interest in photography, for which he requires a particular model of camera that’s been off the market for a number of years. Edward and his family first settled on Videotec cameras out of practicality. As a child, he didn’t know how to cope with batteries running out, so he threw the cameras when it happened. “We went through many of them until we found a sturdy one,” she recalls.

The Littlehales now purchase every Videotec camera they can find on eBay and source spare parts as needed. ”I did have to contact Videotec at one stage as the battery compartment had broken, and they actually sent me spares that they had in their office.” Edward now changes the batteries himself.

When the current wave of straw bans (which, it bears repeating, are harmful to disabled people) diminished the accessibility of Starbucks’ iconic straws, Shannon Des Roches Rosa began collecting them for her son.

“The world is typically an unwelcoming place to non-speaking yet exuberantly autistic people like my son Leo — and he notices. This means he is stressed out a lot, so I think he deserves unfettered access to things that make him feel safe, comforted, and happy, like green plastic Starbucks straws,” she says. “My reaction has been to stockpile: A couple of straws here, a couple of straws there. I don’t know what we’ll do if the straws become completely unavailable, because he is visibly contemptuous of every single plastic straw substitute he has tried so far.”

Social media campaigns and e-commerce sites have been a godsend for autistic people. Not only do they help us source much-needed or much-wanted goods, but they also allow us to do so without having to risk the potential sensory overload of visiting physical stores. But some items are too rare for even the most dedicated and widespread hunt.

Angelica Hill, an autistic single mother, found the ideal job interview shirt at a thrift store for $4.95. Like many autistic people, Hill finds the interview process especially challenging, and she describes herself as “extremely sensory-sensitive.” Having clothing that didn’t cause her discomfort or distraction helped her navigate it a little easier. “[It was] very plain, no extra details. Think a men’s fitted dress shirt, but designed to accommodate breasts. 98 percent cotton, 2 percent spandex, so it had just a little bit of stretch. The arms were the right length, the darts were in the right places, the collar wasn’t too tight, and no gaping between buttons. An absolutely perfect fit.”

When the shirt yellowed with time, Hill tried to replace it through more traditional methods. “The search took me weeks. I’m not great in crowds or malls, so I couldn’t do it all in one day. I think I spent about 20 hours in malls trying to find a shirt that worked. A lot of them were rejected before I tried them on, as I had a budget of $50 before tax and they were well above that. The ones I did try on, though? Awful.”

Hill knew how to sew, though. So she started researching pattern-making, took the original shirt apart, and taught herself how to replicate it. “Now, I don’t have replacement problems with clothes anymore. I’ve solved that in a very permanent way. Plus, I get to avoid malls, and touch all the fabrics in the fabric stores, which are much less busy than malls. Sensory fun-day!”

Sometimes replacing a necessary item isn’t an issue of supply but finances. The unemployment rate among college-educated autistic adults is 85 percent. Meaningful support for autistic individuals is often costly and underfunded.

When access and money aren’t an issue, though, there’s still another hurdle that autistic people can face in trying to replace something important to us: self-consciousness. When you know that you’re different — and how harshly you’ve always been judged for it — it can feel hard to justify these kinds of searches and purchases. Especially when the products might not seem necessary to others.

“As you get into adulthood, you’re kind of told that you’re not supposed to have comfort items,” says Zoey, a 32-year-old autistic social worker. “You’re supposed to have things that are useful. Things that you need, not things that put your mind at rest. It’s not an exclusively autistic thing, but it gets drilled into us that we have to outgrow certain childish tendencies, like having comfort stuffed animals or comfort items that you take with you all the time. If autism is seen as a developmental disorder, then autistic people are seen as people who have to outgrow childhood.”

Zoey herself had to contend with this judgment when she lost her favorite plushie en route to Stockholm in 2018. Dipstick, a stuffed dalmatian she got at the Disney Store when she was 11, had sentimental and practical value. He was the first thing she purchased with her own money and a coping mechanism as she got older. “He’s always had a very, very special place in my heart. He’s kind of a travel companion for all of my years. To the point where it’s like I would consider it really unlucky if I didn’t have Dipstick with me [when I] travel.”

Despondent without him, she decided to look for a new Dipstick. Returning to the Disney Store for a new model wasn’t going to cut it. After one fruitless Amazon search and about 15 different keyword combinations on eBay, Zoey found a similar make for $20. Shortly after the new Dipstick — who does not travel — arrived, she shared the experience during a workshop at her job.

“I could tell it touched a lot of people. My co-worker, the clients, and the people running the group expressed a lot of sympathy for the troubles I had with this goddamned stuffed animal,” she laughs self-deprecatingly before catching herself. “I don’t even know why I feel the need to qualify this. I should be proud! No shame. This means so much more than just buying another thing.”

Sign up for The Goods’ newsletter. Twice a week, we’ll send you the best Goods stories exploring what we buy, why we buy it, and why it matters.

Author: Sarah Kurchak

Read More