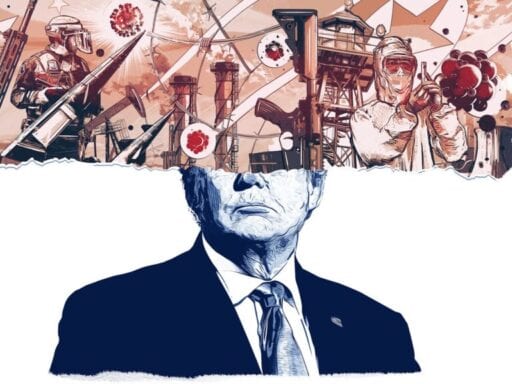

Trump was a gamble. It’s not paying off.

A few months ago, I had dinner with a friend who argued that it was time to rethink Donald Trump’s presidency. After all, the economy was fine, we hadn’t ended up in a nuclear war, and the tough posture toward China was paying some trade dividends. Maybe the madman routine was working. Maybe it really was just a routine, and Trump was managing the presidency well enough. Wasn’t it time for critics like me to rethink their most dire warnings? Wasn’t it time to admit we’d gotten him wrong?

There were, even then, obvious rebuttals, and I made some of them. The lethal mismanagement of the Hurricane Maria response, for instance. But there was a power to the argument. The worst hadn’t happened. Didn’t that require a reckoning?

And then the novel coronavirus came, and President Trump did nothing for week after week, month after month. We sit, still, in the void where a plan should be, forced to choose between endless lockdown and reckless reopening because the federal government has not charted a middle path. Instead, we wake to presidential tweets demanding the “liberation” of states, and laugh to keep from crying when the most powerful man in the world suggests we study the injection of disinfectants. Trump has let disaster metastasize into calamity. The feared collision of global crisis and presidential recklessness has come, and it is not close to over.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19980485/2.jpg)

There is a lesson here, one of particular consequence in an election year. In politics, we evaluate leaders on the clearest of metrics: what did or didn’t happen. Unemployment rose. The bill failed. The war began. We grasp for certainty, and understandably so. In a post-truth age, it is hard enough to discuss reality; it is maddening to try to debate hypotheticals.

But much of any presidency takes place in the murky realm of risk. Imagine that there are 10 horrible events that could befall the country in a president’s term, each with a 1 in 40 chance of happening. If a president acts in such a way that they all become much likelier — say, a 1 in 10 chance — he may never be blamed for it, because none of them may happen, or because the one that does falls during his successor’s term. But in taking calamity from reasonably unlikely to reasonably likely, he will have done the country terrible harm.

The logic works in reverse, too. A president who assiduously works to reduce risk may never be rewarded for their effort because the outcome will be a calamity that never occurred, a disaster we never felt. We punish only the most undeniable of failures and routinely miss the most profound successes.

“No one votes for anyone in government on whether they reduce pandemic risk from 0.9 percent to 0.1 percent in a decade,” says Holden Karnofsky, CEO of the Open Philanthropy Project. “That may be the most important thing an official does, but it’s not how they get elected.”

Of late, I’ve been thinking back to 2017, when Trump began a war of tweets with North Korea, the world’s most irrational nuclear regime. “Just heard Foreign Minister of North Korea speak at U.N.,” Trump wrote. “If he echoes thoughts of Little Rocket Man, they won’t be around much longer!”

Trump’s behavior stunned even Republican allies. Sen. Bob Corker (R-TN), then the chair of the Foreign Relations Committee, warned that the president was treating his office like “a reality show” and setting the country “on the path to World War III.”

But World War III didn’t happen. Trump and Kim Jong Un deescalated. They met in person and sent each other what Trump later called “beautiful letters.” The fears of the moment dissolved. Those who warned of catastrophe were dismissed as alarmist. But were we alarmist? Or did Trump take the possibility of nuclear war from, say, 1 in 100 to 1 in 50?

Moments like this dot Trump’s presidency. His withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal dissolved the only structure holding Iran back from the pursuit of nuclear weapons. What’s followed has been not just a rise in tensions but a rise in bloodshed, culminating with Trump’s decision to do what both President George W. Bush and President Barack Obama chose not to do and assassinate Iranian military leader Qassem Soleimani. The end of that story is as yet unwritten, but possibilities range from Trump’s gamble paying off to Iran triggering a nuclear arms race — and perhaps eventually nuclear war — in the Middle East.

Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris climate accord, alongside his routine dismissals of the NATO alliance, similarly force us to imagine the future probabilistically. In both cases, Trump says he is simply being a tough negotiator, forcing the better deals America deserves. In both cases, unimaginable calamity may — or may not — result. The verdict will not come by Election Day. We will have to judge the risks Trump has shunted onto future generations.

Of the many risks that Trump amplified through lack of preparation, reckless policymaking, or simple inattention, a pandemic is the one that came due while he was still president. But it is not the only one lurking, nor is somehow a charm against other disasters befalling us. Moreover, the coronavirus itself raises the risk of geopolitical crises, of financial crises, of disasters both expected and unexpected, manifesting.

Trump, in his daily rhetoric and erratic mismanagement, is placing big, dangerous bets, but he will not cover the losses if they go wrong: It’s America, and perhaps the world, that will pay, in both lives and money.

The president of the United States is the world’s chief risk officer

If you read the federal budget, the federal government’s primary job comes clear, risk management. More than 50 percent of it is devoted directly to social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, or Medicaid — programs that insure Americans against the risks of illness, old age, and financial disaster. Another 16 percent goes to defense spending, which, in theory, protects us from the risks posed by other countries and terrorist networks. Together, safety net programs and military spending account for almost three-quarters of the federal budget.

The US government is an insurance conglomerate protected by a large, standing army.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19980487/3.jpg)

But the work doesn’t end there. Dig into the remainder of the budget and you find the government devoting itself to the management of more complex and exotic risks, in departments and programs that few Americans ever hear about. As Michael Lewis writes in his excellent book The Fifth Risk, risk management suffuses the entire federal bureaucracy in ways that are dizzying to try to appreciate in full:

Some of the risks were easy to imagine: a financial crisis, a hurricane, a terrorist attack. Most weren’t: the risk, say, that some prescription drug proves to be both so addictive and so accessible that each year it kills more Americans than were killed in action by the peak of the Vietnam War. Many of the risks that fell into the government’s lap felt so remote as to be unreal: that a cyberattack left half the country without electricity, or that some airborne virus wiped out millions, or that economic inequality reached the point where it triggered a violent revolution. Maybe the least visible risks were of things not happening that, with better government, might have happened. A cure for cancer, for instance.

The only way to manage that much risk effectively is to manage the government effectively. But Trump has never pretended to do that, or to want to do that. This can sometimes be mistaken for conservative ideology, but it’s more properly understood as disinterest.

Trump likes being the protagonist in the international drama that is America. He doesn’t want to make sure the world’s most massive, complex, and sprawling bureaucracy is well-run. He has shown little interest in nurturing the parts of the federal government that spend their time worrying about risk. His proposed budgets are thick with cuts to those departments, his proposed appointees often manifestly incompetent, his comments marinated in disrespect for the institution he oversees.

Former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, who originally ran Trump’s transition team, relayed to Lewis a telling comment Trump made about the pre-administration planning, which he considered a waste of time. “Chris,” he said, “you and I are so smart that we can leave the victory party two hours early and do the transition ourselves.”

Each day, the president of the United States receives the President’s Daily Brief: a classified report prepared by US intelligence agencies warning of gathering threats around the globe. US intelligence agencies warned Trump of the dangers of the novel coronavirus in more than a dozen of these briefings in January and February. But Trump “routinely skips reading the PDB and has at times shown little patience for even the oral summary he takes two or three times per week,” reported the Post.

Two problems build amid this kind of executive impatience. First, the president is unaware of the nation’s constantly evolving risk structure. Second, the bureaucracy he, in theory, manages receives the constant message that the president doesn’t want to be bothered with bad news and does not value the parts of the government that produce it, nor the people who force him to face it.

It is, in fact, worse than that. “The way to keep your job is to out-loyal everyone else, which means you have to tolerate quackery,” Anthony Scaramucci, who served (very) briefly as White House head of communications, told the Financial Times. “You have to flatter him in public and flatter him in private. Above all, you must never make him feel ignorant.”

In March, speaking at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention headquarters, Trump unintentionally revealed how much time his underlings spend praising him, and how fully he absorbs their compliments. “Every one of these doctors said, ‘How do you know so much about this?’” Trump boasted. “Maybe I have a natural ability. Maybe I should have done that instead of running for president.”

To state the obvious, this is not a management style that will lead to complex problems being surfaced and solved.

In 2014, after the Ebola epidemic, the Obama administration realized the federal government was unprepared for pandemics, both natural and engineered. And so they built a new team into the National Security Council: the Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense. Beth Cameron was its first leader, and she explains that it was designed to ensure not just a constant focus on the threat, but a bureaucratic structure, and a set of interagency relationships, that were constantly being exercised so coordination could happen fast when speed was most needed.

“Having that in place is really important,” Cameron says, “because it’s in anticipation of a truly catastrophic or existential threat. It is the ability to detect it early. And then it’s the ability to respond efficiently and to practice that at all levels of government.”

That way, when the crisis does come, the government knows how to react, knows who needs to be in the meetings, knows where the power and authority and expertise lie. It can focus on responding to the threat rather than building the structure needed to respond to the threat.

The Trump administration dissolved that office in 2018 as part of John Bolton’s reorganization of the National Security Council. The leader of the team, Rear Adm. Timothy Ziemer, was pushed out. The decision attracted criticism at the time, but the White House defended the call. “In a world of limited resources, you have to pick and choose,” one administration official told the Washington Post. The administration has never explained how or why it chose to deemphasize pandemic risk, nor which threats it decided to prioritize instead.

So neither Trump nor his administration was focused on Covid-19 in the early days, when it would have mattered most. “I think that it’s possible if we’d taken this threat more seriously in mid- to late January, that we could be in a situation where we are containing coronavirus as opposed to having to suppress it,” Cameron says.

I don’t want to overstate the consequence of that one decision: It is possible to imagine an administration that eliminated the office but remained focused, through other agencies or processes, on pandemic risk. But in this case, the dissolution of the office reflected the interests of the executive, and the evidence is everywhere. The administration responded exactly as you’d expect an administration that had shuttered its pandemic response operation to act — which is to say, it mostly did not act.

“When the president stands on top of a table and says, ‘This is super important, super urgent, everyone must do this,’ the government works moderately effectively,” Ron Klain, who managed the Obama administration’s Ebola response, told me. “That’s the best case. When the president is standing up and saying, ‘I don’t want to hear about it, I don’t want to know about it, this doesn’t really exist,’ well, then you’re definitely not going to get effective work from the government.”

The opposite of risk management

In his book The Precipice, Oxford philosopher Toby Ord considers the manifold ways humanity could die or destroy itself — the “existential” risks. He considers asteroids and supervolcanoes, stellar explosions and nuclear wars, pandemic disease and artificial intelligence. Surveying the data and building in his own estimates, Ord concludes that there’s a 1 in 6 chance humankind, or at least human civilization, will be annihilated in the next century.

Among the threats, one factor dominates: other human beings. Ord believes there’s only a 1 in 1,000 chance that a natural disaster — say, an asteroid or a supervolcano — will wipe humanity from the timeline. The likelier outcome is that humanity will annihilate itself, either accidentally or deliberately. It is the chances of a virus bioengineered for lethality, of artificial intelligence that erases us malevolently or casually, of nuclear war or runaway climate change rendering Earth uninhabitable, that drive the risk, in Ord’s view, to 1 in 6.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19980490/5.jpg)

Ord’s estimates are arguable. Perhaps the true probability is 1 in 12, or 1 in 3, or 1 in 50. But it is not zero. And Ord is, purposely, ignoring horrifying outcomes that don’t result in humanity’s extinction. A nuclear war that kills 50 million people does not fit his definition of existential risk. Nor does a bioweapon that kills 200 million, or a violent climate disaster that displaces billions. But the chance of any, or all, of these is inarguably higher.

Trump raises the risk of virtually every threat on Ord’s list. In some cases, he does so directly: in withdrawing America from the Paris climate accord and turning the Environmental Protection Agency over to oil industry executives, he has directly increased the risk of runaway climate change. In refusing to renew the New START treaty with Russia and dissolving the Iran nuclear deal, he has directly increased the likelihood of nuclear proliferation. In dismantling the government infrastructure meant to protect us from biological and natural pandemics, he has increased America’s vulnerability to pandemics — as we are seeing.

But the most important argument Ord makes is this: Risks, even across vastly different spheres, are correlated. There are forces, events, and people that simultaneously raise — or lower — the risk of runaway climate change, nuclear war, pandemics, and reckless AI research. The simplest way to raise all of them at once, Ord suggests, would be a “great-power war.”

Take a war between the US and China. It would raise the chances of nuclear launches, engineered bioweapons, and massive cyberattacks. And even if it never got to that point, the increase in hostilities would impede the cooperation needed to slow or stop climate change, or to regulate the development of artificial intelligence. And yet, increasing hostilities with China has been the hallmark of Trump’s foreign policy. Even prior to the coronavirus, the US-China relationship was “at the worst point since the forging of the relationship in 1972,” says Evan Osnos, who covers China for the New Yorker. Now the situation is much worse.

The Trump administration’s initial response to the coronavirus, and the one of which it remains most proud, was closing travel to and from China. It is possible that policy bought us time, but it was time we wasted. The coronavirus made its way to the US from Europe, and the Trump administration turned to blaming China. The president began calling it the “Chinese virus.” His administration stalled a United Nations Security Council resolution on the coronavirus because it didn’t pin sufficient blame on China for the virus’s origins. China has responded in kind, suggesting the US military carried the coronavirus into the country and expelling US journalists.

During a recent interview on Fox Business, Trump said of President Xi Jinping, “I just, right now, I don’t want to speak to him,” and threatened to “cut off the whole relationship.”

It is important not to pretend the US-China relationship is easy, nor that China has been, itself, a good actor amid the coronavirus (or even more broadly). But we are thinking here in terms of catastrophic risk, and it is clear that the deterioration of the US-China relationship worsened global pandemic risk.

“Ask yourself: What would’ve happened if we’d had more constructive conversations with China over the past few years?” says Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT). “Would they have been more willing to share information on coronavirus early? I don’t know the answer to that question. But we created a relationship that was purely antagonistic.”

Reasonable people can, and do, disagree on ideal China strategy. But in this case, there has been no strategy at all. An administration that wanted to confront China successfully would strengthen America’s other alliances, build US influence in Asia, reinforce our commitments in Europe, invest in retaining the world’s respect and trust. Trump has done none of that. Instead, has surrounded himself with professional China antagonists, like Peter Navarro, ratcheted up tensions continually, and made a hobby out of alienating and unnerving traditional allies. Now, in a moment that demands global cooperation, the relationship is in collapse, and America’s international capital is at a low ebb.

“We increasingly feel caught between a reckless China and a feckless America that no longer seems to care about its allies,” Michael Fullilove, head of Australia’s largest think-tank, told the Financial Times.

The rising tensions between the US and China worsen almost every existential or catastrophic threat facing the US. Coronavirus could have been a warning, a signal of how quickly catastrophe can overwhelm us in the absence of cooperation. Instead, it’s been used to pump more hostility, more enmity, more volatility into the most important bilateral relationship in the world. That is a political choice Trump has made, a risk he is running on behalf of future generations.

“I know we talk about trust all the time as the missing ingredient, but it matters when it comes to international politics,” Osnos says. “The big blinking risk is that there is not an assumption on the Chinese and the US sides that the other one basically has the same interest, which is global stability. There is a real feeling that the other one is seeking to hurt.”

The risk is Trump

In normal times, the worst risks we face slip easily from our minds. We think of the threats we know, the ones we faced the year before and the year before that and the year before that. This is called “availability bias,” and it is natural: We think more about the dangers we’ve seen before than the ones we haven’t. Yet the worst risks are, by their nature, rare — if they came due constantly, humanity would be ash.

As a result, we conflate the unlikely and the impossible. This pandemic, if nothing else, should shatter that conflation. It is hard to pretend the worst can’t happen when you haven’t been able to enter a store or see your parents for six weeks. And let’s be clear: coronavirus is not the worst that can happen. The H5N1 virus, for instance, has a mortality rate of 60 percent, and scientists have proven that it can mutate to become “as easily transmissible as the seasonal flu.”

Even scarier is the possibility of human-engineered pandemics. As bad as the coronavirus is, Bill Gates told me, “it’s not anywhere near bioterrorism — smallpox or another pathogen that was intentionally picked for a high fatality rate as well as delayed symptoms and a high infectious rate.”

We play for the highest of stakes. We must do what we can to improve our odds.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19980495/6.jpg)

No one bears a heavier burden in that respect than the US president. But Trump is reckless with his charge. That reflects, perhaps, his own life experience. He has taken tremendous risks, and if they have led him to the edge of ignominy and bankruptcy, they have also led him to the presidency.

But he has always played with other people’s money and other people’s lives. “The president was probably in a position to make riskier decisions in life because he was fabulously rich from birth,” says Murphy. “But it’s also true he has had a reputation for risk not backed up by reality. His name is on properties he doesn’t own. We think of him as taking risk in professional life, but a lot of what he does is lend his name to buildings with risks taken by others. He’s built an image as a risk taker, but it’s not clear how much risk he’s taken.”

In electing him president, however, we have taken a tremendous risk, and it isn’t paying off. Right now, the Trump administration is flailing in its health and economic response to a pandemic ravaging our society. The country’s chief risk officer failed, largely because the country hired someone who didn’t want to do that job. Maybe, next time, we should hire someone who does.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Ezra Klein

Read More