It might not be the “game changer” Covid-19 treatment the president promised.

President Donald Trump continues to tout hydroxychloroquine, a common anti-malaria drug, as a potential treatment for Covid-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus — even though there is no evidence as to whether it is effective or even safe to use in these cases.

In televised press conferences and on his Twitter account, he’s sought to promote the drug as a treatment when coupled with the antibiotic azithromycin, also known as “Z-Pak.”

“HYDROXYCHLOROQUINE & AZITHROMYCIN, taken together, have a real chance to be one of the biggest game changers in the history of medicine,” he tweeted Saturday.

Trump’s boosting has sent many Americans clamoring for the drug, creating shortages for patients who need it, including those with autoimmune disorders who are inherently vulnerable to Covid-19, and encouraging people to self-medicate without understanding the potential benefits or risks.

A man in Arizona died after he and his wife drank a poisonous fish tank cleaner that contained the same active ingredient; his wife said she recognized the chemical name when Trump talked about hydroxychloroquine on TV.

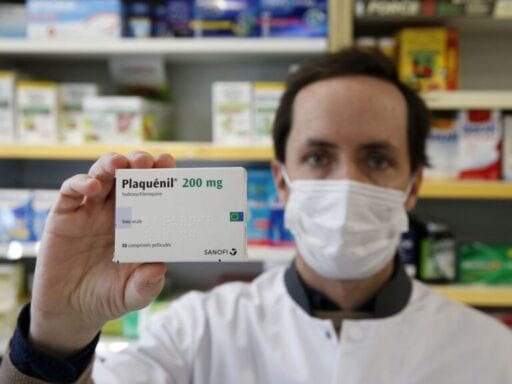

Clinical trials are underway, but there is so far little firm evidence that hydroxychloroquine, also known by its brand name Plaquenil, is effective in treating coronavirus: One study in France found that patients who took the drug along with an antibiotic cleared the virus from their bodies more quickly. A study that tested the drug in a randomized controlled trial in China did not find a difference in recovery rates, but like the French study, it involved only a small group of patients,

There are a lot of reasons why doctors are hoping hydroxychloroquine can treat coronavirus: It has already been approved by the Food and Drug Administration as a treatment for malaria and certain autoimmune diseases, including lupus, and there are relatively cheap, generic versions of the drug available. That would make it easier to produce and disseminate on a wide scale.

Even if the drug were definitely effective, though, scientists have known for decades that the drug carries adverse psychiatric side effects and can also cause deadly heart complications. Only clinical trials can clarify who would benefit and who would be at too big a risk.

Prescribing the drug now is “kind of a ‘last resort’ measure for those with severe disease,” Joshua Michaud, associate director for global health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, told Vox, later adding: “I would be more concerned about having large numbers people, including those without symptoms or only mild symptoms, taking this drug because of the risk of negative side effects and unclear benefits at this point.”

But Americans aren’t waiting to stock up on hydroxychloroquine — hurting people who rely on it to treat other conditions.

Trump has touted hydroxychloroquine as a “game changer” ready for immediate use

Hydroxychloroquine, a derivative of chloroquine, is one of the options being tested as doctors seek effective treatments for Covid-19.

At least 13 clinical trials around the world are in progress or have been announced, giving researchers the opportunity to try to evaluate its effects on patients with the virus.

The research is still in very early stages. Far more studies would need to be done before it could even be deemed effective, let alone widely prescribed to patients.

Still, Trump has repeatedly and confidently talked about hydroxychloroquine coupled with azithromycin as a potential treatment for the virus, retweeting news stories about a French doctor who claimed that he had a 100 percent cure rate by treating patients with the two drugs.

Fox News hosts Laura Ingraham and Sean Hannity have also been touting the drug on their shows, dismissing experts’ concerns and claiming that there isn’t enough time for robust clinical trials.

“At my direction, the federal government is working to help obtain large quantities of chloroquine,” Trump said during a press conference on Monday. “We think tomorrow, pretty early, the hydroxychloroquine and the Z-Pak I think is a combination is looking very, very good and it’s going to be distributed.”

But any broad distribution of hydroxychloroquine would need far more evidence that it is both safe and effective. Hydroxychloroquine is still in the first phase out of three of clinical trials, and the majority of drugs for infectious diseases that seem promising in the first phase don’t ultimately make it to market.

Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health, has said that he has no data to rely on that the drug is safe for people who’ve tested positive for coronavirus, nor any data that proves it is effective. He’s dismissed the idea that there is a “magic drug.”

In an appearance on Fox News, he said he would consider taking the drug himself as a potential coronavirus treatment, but only in a controlled, clinical trial setting.

“If I had a situation where I need a drug, I would look around to see if there was a clinical trial that would give me access within the contours of a clinical trial,” he said.

Some preliminary studies on hydroxychloroquine are hopeful — but they’re very, very preliminary

Experts have expressed skepticism of preliminary studies about the effectiveness of the drug.

Trump tweeted the study from France, which was widely publicized but controversial: It found the presence of the virus in patients’ blood dropped after they received the drug, some in combination with azithromycin.

But that study, done on only 26 patients, has been criticized: “The issues with these studies go beyond their small size or the fact that early promises, in research, often don’t pan out,” Stat News’s Matthew Harper wrote. “It goes to one of the big truths about how doctors, eager to see a new drug succeed, can subconsciously lie to themselves with clinical studies: To be trustworthy, these studies often need to be randomized,” and the French study was not.

A more recent study from China, which was randomized but still very small, found that those who received the drug were no better off in fighting the virus than those who didn’t.

On Tuesday, additional clinical trials began in New York, a hotspot of infection. The governor’s office announced that it had obtained 70,000 doses of hydroxychloroquine, along with 750,000 doses of chloroquine, another closely related malaria drug, and 10,000 doses of azithromycin.

The potential adverse side effects of hydroxychloroquine are well-documented. The drug, which is a less toxic version of chloroquine, can carry adverse psychiatric side effects that can occur even after just a single dose, though it’s more common after high doses. Those manifest differently among patients, ranging from anxiety, insomnia, and nightmares to paranoia, hallucinations, personality changes, and suicidal ideation.

In combatting malaria, doctors have accepted these potential side effects in cases where patients would otherwise die.

“The risk of psychosis is of little relevance if one is dead, the thinking goes,” Remington Nevin, an epidemiologist who specializes in drug safety, tweeted.

Hydroxychloroquine can also disrupt normal heart functions, increasing what’s called the “QT interval” — the time it takes for the heart to contract and relax when pumping out blood. If that interval becomes too long, it can cause an irregular heartbeat or arrhythmia that can lead to fainting and, in serious cases, sudden death, putting patients at higher risk of strokes and heart failure.

The antibiotic azithromycin, which has been used alongside hydroxychloroquine in studies to treat coronavirus, also carries these potential cardiac side effects. For elderly patients and those with preexisting conditions that make them susceptible to complications from Covid-19, these risks are particularly acute.

It’s not a complete shot in the dark, however: Hydroxychloroquine does have certain anti-viral properties (though it’s not clear whether those properties make it effective against the coronavirus), and some lab cell culture studies have shown that the drug can work against SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for Covid-19. But scientists haven’t tested it adequately in humans — and we already know what can go wrong.

“We want to make sure the negative side effects don’t outweigh any positive effects,” Michaud said. “There really is no substitute or short cut around doing trials to answer the safety and effectiveness questions.”

Soaring demand for hydroxychloroquine is putting patients who already take it at risk

None of this has stopped Americans from seeking out hydroxychloroquine — sometimes in dangerous or potentially illegal ways.

BuzzFeed reports that a man died after self-medicating with a fish tank cleaning solution that shared some of the same ingredients. Other reports suggest there’s a run on the drug itself, with some even crossing the border to buy it from Mexican pharmacies.

ProPublica reported that pharmacists are running out of the drug because, in some cases, doctors appear to be prescribing it for themselves or their family members, calling in high numbers of prescriptions simultaneously or asking for more tablets than usual. One pharmacist described it as “fraud.”

Even some hospitals have started stockpiling the drug and prescribing it to patients on an off-label basis.

All of this has made it harder for people who need the drug to get it.

BuzzFeed reported that Kaiser Permanente, a major health care network, informed patients that it would stop filling their hydroxychloroquine prescriptions in order to maintain a supply for the “critically ill with COVID-19,” thanking them for their “sacrifice.”

Patients who are already prescribed have started stocking up too, worried about shortages.

“After I heard my medication mentioned on the news, I rushed to obtain a 90-day supply,” Stacy Torres, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of California at San Francisco who takes the drug for a condition known as Sjogren’s syndrome, wrote for the Washington Post. “A sympathetic pharmacist told me, ‘You’re exactly the person I want to get this medication to’ — before breaking the news that pills are on back order.”

Some states are working to prevent this. Nevada Gov. Steve Sisolak blocked the use of anti-malaria drugs for coronavirus patients to protect against stockpiling. Now, Nevadans can only obtain prescriptions for a 30-day supply to ensure it’s available for “legitimate medical purposes,” such as treating lupus and arthritis.

The run on hydroxychloroquine stems from fear: Americans are facing a frightening pandemic and looking for hope. Trump is talking up an as-yet-unproven drug to try to give it to them.

But the consequences of his rhetoric and the accompanying hype for hydroxychloroquine are being felt by people with autoimmune conditions like lupus, who will be even more vulnerable to complications from Covid-19 if they can’t get the medication.

“For those with grave autoimmune diseases,” Francisco wrote, “not having access to this medication might be fatal.”

Author: Nicole Narea

Read More