The president will announce his nominee Monday night (unless he tweets it out first). He’ll probably pick one of these four.

President Donald Trump plans to announce his pick for the Supreme Court nominee to replace retiring Justice Anthony Kennedy on Monday, July 9, at 8 pm Eastern time, according to Fox.

Unless he just tweets it out before then — something Axios reports he’s considering.

Arguably, the timing of Trump’s Supreme Court announcement is every bit as big a surprise at this point as who he’s going to pick. In the ongoing reality show that is America’s Next Top Supreme Court Justice, reports have made it clear that Trump has narrowed his initial public list of 25 names down to four: current appellate judges Brett Kavanaugh of the DC Circuit; Amy Coney Barrett of the Seventh Circuit; Raymond Kethledge of the Sixth Circuit; and Thomas Hardiman of the Third Circuit.

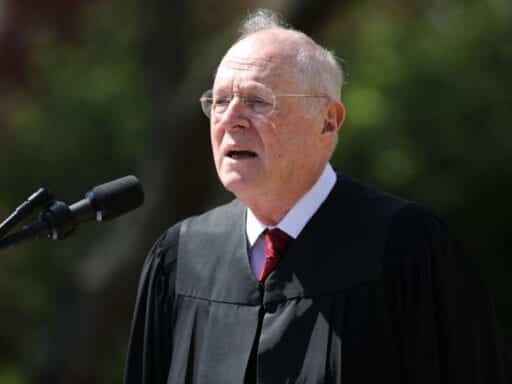

Brett Kavanaugh

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Chip Somodevilla/Getty ImagesCurrent position: Federal appellate judge (DC Circuit Court of Appeals)

Why Trump picked him: Brett Kavanaugh has about as long and high-profile a record in Republican legal circles as anyone on this list. A former clerk to Anthony Kennedy, as well as appellate judges Alex Kozinski and Walter Stapleton, he represented Cuban child Elian Gonzalez pro bono during the conservative battle to keep him from returning to Cuba, and was one of the George W. Bush campaign’s lawyers in the Florida recount.

Before that, though, Kavanaugh was a protegé of Kenneth Starr, whom he served both in the solicitor general’s office under George H.W. Bush and as independent counsel during the investigation into the Clinton family’s Whitewater real estate deal. He was a principal author of the Starr Report, which detailed Bill Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky and misrepresentations of that affair in sworn testimony.

“As a prosecutor, Kavanaugh set a bracing literary standard (‘On all nine of those occasions, the President fondled and kissed her bare breasts…’),” the New Yorker’s Jeffrey Toobin recalled in 2012, “but his work as a judge may be even more startling.” Toobin cites Kavanaugh’s opinion on the DC Circuit when considering a constitutional challenge to the Affordable Care Act:

[A]ccording to Kavanaugh, even if the Supreme Court upholds the law this spring, a President Santorum, say, could refuse to enforce ACA because he “deems” the law unconstitutional. That, to put the matter plainly, is not how it works. Courts, not Presidents, “deem” laws unconstitutional, or uphold them. “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is,” Chief Justice John Marshall wrote in Marbury v. Madison, in 1803, and that observation, and that case, have served as bedrocks of American constitutional law ever since. Kavanaugh, in his decision, wasn’t interpreting the Constitution; he was pandering to the base.

It’s hardly his only stridently conservative opinion on the DC Circuit. In a profile for Ozy, Daniel Malloy notes, “Kavanaugh this year declared that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is unconstitutional, given the agency’s independence and unitary structure, and he has voted repeatedly to slap back aggressive regulations from Barack Obama’s Environmental Protection Agency.”

But as Trump has considered Kavanaugh to replace Kennedy, some conservatives have started to voice concerns that the judge isn’t reliably conservative enough. Some conservatives, including Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY), have pointed to Kavanaugh’s record on health care; others are concerned that Kavanaugh told senators during his DC Circuit confirmation hearing that he’d respect precedent on abortion and declined to share his views on Roe v. Wade. This could very easily be the typical DC song and dance of pretending not to believe what he clearly believes on key questions of jurisprudence, but it appears to be a concern.

The biggest problem for Kavanaugh, though, might be his association with Bush. Multiple reporters have heard from aides that Trump is suspicious of anyone in the GOP who was too closely tied to the Bushes. “You hear the rumbling because if you’ve been part of the establishment for a long time, you’re suspect. Kavanaugh carries that baggage,” one conservative organizer told the Washington Post.

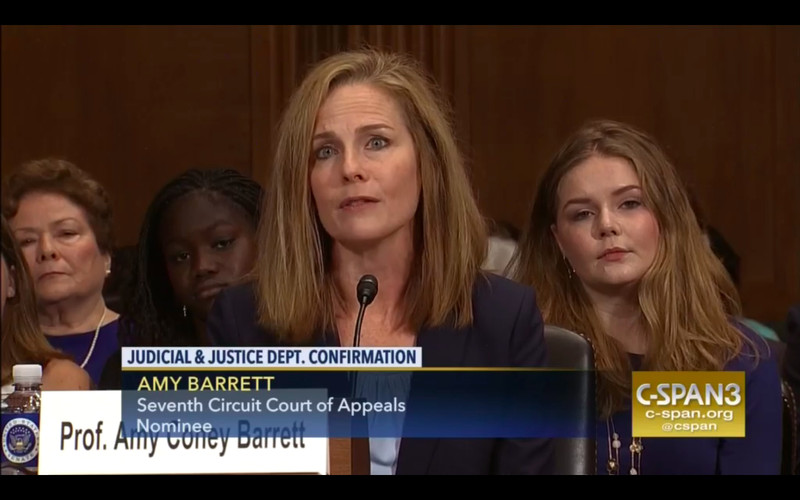

Amy Coney Barrett

C-SPAN

C-SPANCurrent position: Federal appellate judge (Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals)

Why Trump picked her: Amy Coney Barrett, only 46, is relatively new to the bench; her first appointment came from Trump in 2017. She only got her commission last November. (Before joining the federal bench, Barrett was a clerk to conservative appellate Judge Laurence Silberman as well as Antonin Scalia, and a longtime professor at Notre Dame.) But Clarence Thomas was barely on the circuit court for a year when he was elevated to the Supreme Court, and there’s no reason Barrett couldn’t follow in his footsteps.

Barrett might be fading in Trump’s esteem. Trump has said he wants a Supreme Court nominee with degrees from Harvard or Yale; Barrett’s law degree comes from Notre Dame Law School. And according to one report, she performed poorly in her one-on-one interview with Trump.

But the best thing Barrett has going for her in Trump’s eyes might be how worried liberals are about her. Most attention has been to her religious practices — she’s a member of a Catholic revivalist group called “People of Praise,” in which members swear an oath of loyalty and give each other input on personal life decisions.

The question is to what extent Barrett’s religion affects her jurisprudence. Liberal groups have identified writing on questions of Catholic faith and constitutional interpretation as concerning, noting a piece she co-authored that rejected Justice William Brennan’s argument that Catholic judges should always hold the Constitution as more important than their religious faith.

In her confirmation hearing for the Seventh Circuit, Barrett asserted that these were her co-author’s views, not her own. But the hearings earned headlines due to a controversial line of questioning from Democratic Sens. Dick Durbin (IL) and Dianne Feinstein (CA), who asked her repeatedly about her Catholic faith. Durbin asked, “Do you consider yourself an orthodox Catholic?” while Feinstein commented, “When you read your speeches, the conclusion one draws is that the dogma lives loudly within you.”

That sort of questioning — which conservatives characterized as Feinstein trying to impose an unconstitutional “religious test” for office on Barrett — could make for some feisty Supreme Court confirmation hearings. Some (like Margaret Hartmann of New York magazine) have speculated that Trump might relish the idea of partisan conflict during a hearing to fire up the base.

Barrett also argued that the birth control benefit in the Affordable Care Act impinges on religious liberty, argues that cases like Roe v. Wade might not need to stand as precedents if future courts judge them to be wrongly decided, and has explicitly asserted that the “original public meaning” of the Constitution must be upheld, even though that “adherence to originalism arguably requires, for example, the dismantling of the administrative state, the invalidation of paper money, and the reversal of Brown v. Board of Education.”

Barrett was ultimately confirmed with only three Democrats (Joe Manchin, Joe Donnelly, and Tim Kaine) voting in favor. But an elevation to the Supreme Court would force a much larger dispute about what, exactly, she believes the original meaning of the Constitution requires.

Some court-watchers are concerned that Barrett has been too explicit on abortion to be confirmable. But others speculate that overturning Roe v. Wade might be less galvanizing to progressives if a woman casts the decisive fifth vote.

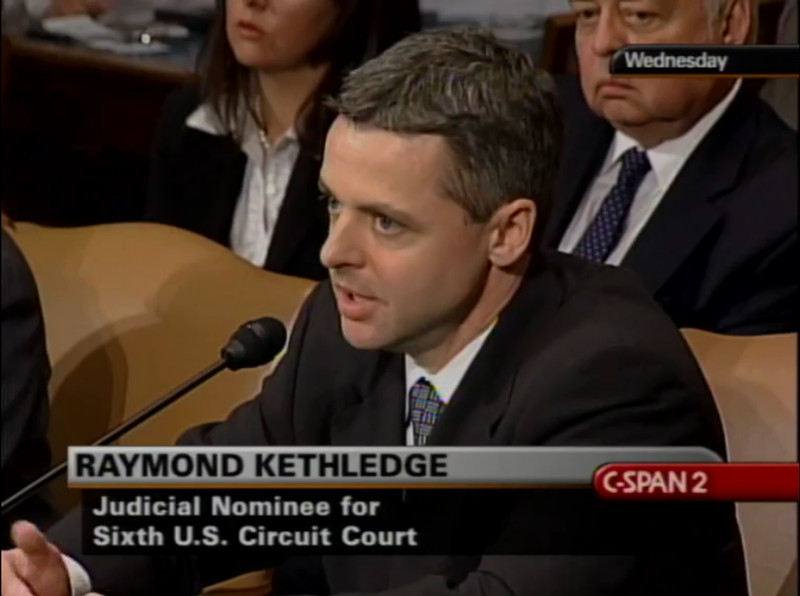

Raymond Kethledge

C-SPAN

C-SPANCurrent position: Federal appellate judge (Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals)

Why Trump picked him: Raymond Kethledge appears to be the kind of judge who very much enjoys telling people why they’re wrong.

In 2014, he wrote an opinion upholding the use of credit checks to screen potential employees at Kaplan, a for-profit education firm, defending the company from an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) lawsuit. The opinion noted, pointedly, that use of credit checks was permitted by the EEOC’s own hiring guidelines — an act of gotcha jiujitsu that was praised by the Wall Street Journal.

More recently, in a case involving the IRS’s alleged persecution of conservative political groups, Kethledge forcefully ordered the agency to turn over information — and rejected the tactic it had tried to use in its defense as an “extraordinary remedy” not appropriate for a suit like this.

But if you’re picturing Kethledge as a mini-Scalia, all flashy rhetoric and black-and-white conservative principle, you’re off the mark. He was a Senate Judiciary Committee staffer under Michigan Republican Spencer Abraham in the 1990s, but Abraham, while a founder of the Federalist Society, was also a pro-immigration Arab American who lost (to Debbie Stabenow) after being attacked as a terrorist sympathizer. And during his confirmation hearings before the committee in 2003, he emphasized his pro bono work with criminal defendants and low-income residents trying to keep their homes.

A 2013 Kethledge opinion, which is already being cited outside his home circuit, says “there are good reasons not to call an opponent’s argument ‘ridiculous’” — not the least of which, he elaborates, is that you might be wrong. It’s hard to imagine hearing that sentiment from Scalia — or from the president now offering to appoint Kethledge to the highest court in the land.

Thomas Hardiman

Roy Engelbrecht

Roy EngelbrechtCurrent position: Federal appellate judge (Third Circuit Court of Appeals)

Why Trump picked him: Donald Trump’s been known to say that “the police in our country do not get respect.” That is assuredly not Thomas Hardiman’s fault.

On the Third Circuit, Hardiman has consistently sided with law enforcement against defendants and inmates. He ruled that a policy of strip-searching jail inmates didn’t violate the Fourth Amendment’s protections against unreasonable search (an opinion the Supreme Court upheld). He’s also written, in dissent, that the First Amendment does not give citizens the right to tape police — something with which every state in the union currently disagrees.

Hardiman’s pre-judicial career is full of the kinds of things liberals and Democrats don’t like: He donated to Republican candidates before being appointed to the bench (something that is neither illegal nor, to most legal experts, a big deal), and he represented plenty of political clients and political cases while he was in private practice. Most of this is insignificant: Just like it’s a defense lawyer’s job to defend murderers, it’s a civil lawyer’s job to defend companies accused of discrimination.

But it’s ironic that one of Hardiman’s most high-profile cases was a housing discrimination suit against a company accused of conspiring to keep out low-income clients — given that the president who might appoint him to the Supreme Court, early in his own career, settled a housing discrimination suit of his own against the federal government.

Perhaps most relevant to Hardiman’s chances, though, is that he was reportedly Trump’s second choice after Neil Gorsuch to replace Antonin Scalia. Despite his conservative record, grassroots right-wing activists freaked out when his name was floated, arguing he could be a stealth liberal. (The evidence for this was shockingly weak.) Perhaps, then, second time’s the charm?

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png