American Compass founder Oren Cass on why conservatives need to challenge free-market economic orthodoxy.

Five years ago, Oren Cass sat at the center of the Republican Party. Cass is a former management consultant who served as the domestic policy director for the Mitt Romney campaign and then as a senior fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute. But then he launched an insurgency.

Today, Cass is the author of The Once and Future Worker and the founder and executive director of American Compass, a new think tank created to challenge the right-wing economic orthodoxy. Cass thinks conservatism has lost its way, becoming obsessed with low tax rates and a quasi-religious veneration of markets.

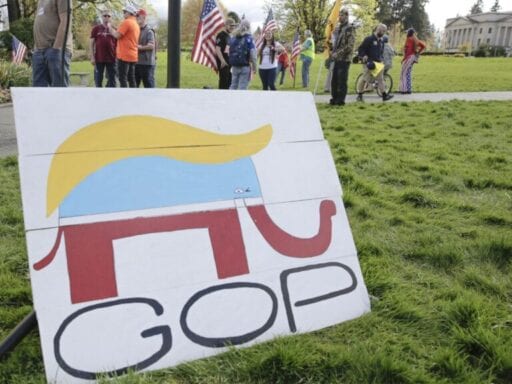

What conservatives need, he thinks, are clear social goals that can structure a radically new economic agenda: a vision that puts families first, eschews economic growth as the be-all-end-all of policymaking, and recognizes the inescapability of government intervention in the economy. Trump is likely — though not certain — to lose in 2020. And then, Cass thinks, Republicans will face a choice: to return to a “pre-Trump” consensus or to build a “post-Trump future” — one that, he hopes, will prevent more Trump-like politicians from rising.

In this conversation, Cass and I discuss how current economic indicators fail, the relationship between economics and culture, why Cass believes production — not consumption — should be the central focus of public policy, the problems with how our society assigns status to different professions, the role that power plays in determining market outcomes, and the conservative case against market fundamentalism.

We also talk about why Cass supports labor unions and industrial policy but not a job guarantee or publicly funded child care, what the future of the Republican Party after Donald Trump looks like, whether Cass’s policies are big enough to solve the problems he identifies, and more.

An edited excerpt from our conversation follows. The full conversation can be heard on The Ezra Klein Show.

Ezra Klein

A major theme of your book is the disconnect between economic statistics and genuine prosperity. What are the indicators of social well-being and success that we should be paying less attention to? Which ones should we be paying more attention to?

Oren Cass

I think the one we should be paying less attention to is aggregate GDP.

We do a lot of analysis at the aggregate level. And in a country as large and diverse as ours, to say that growth was X percent last year really tells you very little about how any given group of people in any given place is faring. Being able to focus in and ask, “How are people who are not doing so well doing?” is vitally important.

The second piece of that is GDP, which is technically a measure of output, but we tend to analyze it after we’ve redistributed and moved money around and understand it as a measure of consumption. I think consumption is great. I’m not an anti-growth, anti-materialism guy at all. But I think, at the margin, increases in consumption when it’s the size of your television probably aren’t all that correlated to individuals’ well-being or happiness, the health or strength of their families, their communities, and especially their ability to carry forward healthy families and communities through their children to the next generation.

I think we should pay more attention to those things: Are people forming stable families? Are they able to achieve self-sufficiency, provide for themselves, contribute to their communities? And then do we have a sustainable process where that is reproducing into the next generation so that the folks who are kids today or leaving high school today are in a position to do that as well.

Ezra Klein

Let’s get specific: What is your basket of indicators that you think is most important?

Oren Cass

I think one that’s really important is the savings rate. Not the aggregate savings rate. I would want to know the savings rate for the typical household and specifically the typical household with children living in the household. If you see a high savings rate, that tells you both that attitudinally people are saving and investing and planning toward a future, and economically that they are not reliant on transfer payments and trying to just pay that month’s bills. They actually have reached a place where they are able to be net productive contributors. So that’s an economic measure that I think is very important.

Related to that is a question like the median wage — I think that’s an important one to look at. I think family status is very important. Today, families are not forming in the first place. People who have kids are not getting married or people are not having kids at all. So both the marriage rate and the fertility rate are really important to look at. Then the combination of those would tell you the share of folks who are essentially in stable relationships and the share of kids who are being raised in those kinds of households.

The last thing I think is really important is looking at the health of local economies and communities. There’s a fascinating chart that comes from an analysis that the New York Times did, where they just looked county by county at the share of personal income that came from transfer payments. They compare the ’70s where essentially across all counties you were at 10 to 20 percent personal income from transfers to the late-2000s where you get up to 30, 40 percent in most places and up above 50 percent in some.

Aside from how you feel about government spending or redistribution, that transition tells you about an economy that is not working correctly. Many, if not most, parts of the country cannot actually produce things that the rest of the country or world wants. They are instead literally exporting need. They are trading enrollment of people in their communities on these programs for the resources they want from elsewhere. Getting out of that model, I think, is vital to having a viable nation for the long run.

Ezra Klein

This feeds in to your core argument in the book, which you call “The Working Hypothesis,” and almost acts like a working goal: “that a labor market in which workers can support strong families and communities is the central determinant of long-term prosperity and should be the central focus of public policy.”

And I want to talk about that and what that means, but I also want to distinguish it from what you are trying to supplant. So if that is the Oren Cass goal or hypothesis, what do you think the dominant goal or hypothesis in the Republican and Democratic Parties traditionally has been?

Oren Cass

The way I describe it is growth plus redistribution, the idea that we’re going to get aggregate GDP up and that creates a bigger pie. And once we have the bigger pie, we might fight about how exactly to cut it out, but at the end of the day, everybody can have more pie. And so I like, tongue in cheek, call this “economic piety.”

I think it’s the model that predominated roughly from certainly sort of the ’80s through to the last few years and arguably still predominates for most folks in Washington.

The two parties had different views of how you get the most growth, and then they had different views of how much redistribution you do. But I think at the end of the day, there was widespread agreement that as long as your combination of factors led to the growing pie for everybody, you could be confident that you were succeeding.

Ezra Klein

And how is your view different?

Oren Cass

I think pie is nice, but to overstretch the metaphor, I think it matters who’s baking the pie. A lot of what contributes to the well-being and life satisfaction and family formation, strength, and community strength comes down to the production side of the equation.

Do I do something that is valued by others? Do I create something of value that contributes to the well-being of others? I think that is vital to all of these things that we care about much more at the end of the day than the consumption side.

In an ideal world, you get both: You grow the economy in a way that includes and involves everybody as a producer and that ensures they are all becoming more productive over time. And then everybody gets more pie and can feel like they helped bake it. But I think that the way that we pursued the growth from both parties either just disregarded the production side of the equation or actively undermined it.

Standard economic analysis says consumer welfare is what matters. Economic analysis says the goal is to get as much as you can while doing as little work as possible. And so the way we evaluate policy has been to say, “How much stuff can we produce to consume?” And we either don’t care or even devalue the work done to produce it. And I think that led us pretty far astray.

Ezra Klein

Something that you’ve been pushing and has been the locus of some of your fighting with others in the conservative movement is around industrial policy. Can you tell me a bit about your thinking there? What kind of industrial policy would you like to see America have?

Oren Cass

At the conceptual level, the important thing to recognize is that there are some things markets are very good at and some things markets don’t do. If we are concerned about particular industries — particular types of economic activity that we think are going to be valuable to the development of the national economy over time — that’s not something private investors are going to think about when they allocate their capital.

If we care about it, we are going to have to use public policy to advance it. And I think we should care about it. I think the industrial economy — by which I mean broadly manufacturing, resource extraction, transportation, infrastructure, things in the physical world — are incredibly important to the health of the overall economy and its trajectory in the long run. They also happen to be incredibly important as a form of employment because they tend to be the place where especially less-educated, especially male, workers, are most productive. So those kinds of jobs actually, I think, have particular social value.

If that’s the case, we need to design public policies that are going to encourage investment in those areas. Then the layer that gets put on top of that is that we are now in a global economy where other countries are doing this. The quintessential example is China, which has a very aggressive policy to try to attract this kind of economic activity to its economy. And if we don’t want it to all go there, then we are going to have to respond. It’s a funny situation where you would think free markets and free trade are synonymous, but in fact, to the extent you’re going to have free trade, you’re going to have to get involved in the market when you’re trading partners for getting involved in their markets.

There are lots of ways to go about this. American Compass just put out this big symposium called “Moving the Chains” focused on supply chains, where we brought together experts from all different fields all across the political spectrum to just talk about how many different ways there are to think about this.

Funding for research and development. Our tax code could be a lot friendlier to this kind of activity. I think in some cases we need domestic sourcing requirements. We can just say we’re not going to interfere in the market, but we’re going to tell you, you got to buy somewhere in this domestic market. Different ways we think about education, different ways we think about regulation, different ways we think about antitrust.

It all comes together, I think, where instead of just economic piety, if this is something we care about, we should do policy differently.

Ezra Klein

One thing I’ve seen you write about is how the central fight on the right currently is about whether after Trump the Republican Party reverts to a pre-Trump or post-Trump state. I’d like to hear you describe that fight the way you see it. What does it mean for the Republican Party, too? If Trump loses in November or if he just wins a second term and leaves after that to go to a pre-Trump straight versus a post-Trump state?

Oren Cass

I think there’s a fascinating dynamic on the right-of-center right now where if you look within institutions — if you look at individuals working the various think tanks in media and in agencies and congressional offices — there’s just a ton of fascinating people doing fascinating work: rethinking first principles, challenging orthodoxies. It’s really exciting. Some of that is just a result of Trump sort of wiping the table clean and there being a sense that anything goes.

Yet if you zoom out and look at the institutions, you see virtually none of that. You see a fairly monolithic approach that basically says: If we keep our heads down, this, too, shall pass — there’s no reason the 2024 primary can’t be a replay of 2016 if there had been no Trump. That dynamic, I think, is a real problem.

I think that fight is playing out where you see a lot of institutions and important folks within those institutions who genuinely believe that what the Republican Party represented and what conservatism represented from 2000 to 2015 was the right place to be — and we just need to get back to that.

Then you have a lot of people who are saying, “No, that’s not right.” As a conceptual matter, a lot of these ideas were either just wrong or outdated and not applicable to current circumstances. On top of that, there’s a political problem that the kind of coalition that those ideas were built for does not seem to have any potential as a majority coalition. So we need to do better than that, and this is the time to be doing it.

Once you accept that broad frame — that we should be thinking about post-Trumpism, not just a return to pre-Trumpism — then there are still any number of fights to have about the specifics. But the premise of forming American Compass was to say, at the institutional level, we need to start building some things that can be homes for post-Trumpism. My hope is that many of the great right-of-center institutions continue to thrive, and with our work from the outside, we can kind of nudge them and alter the stream that everybody’s swimming in.

In my view, that change has to happen mostly for the substantive reasons: The pre-Trump “conservative” platform and way of thinking was not the right one. And it needs to change.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Ezra Klein

Read More