Muslim mystics believed suffering and solitude can make us better.

“I’m a Muslim boy of Iran and the American South who is politically most at home in the Black church and spiritually most at home in Rumi.”

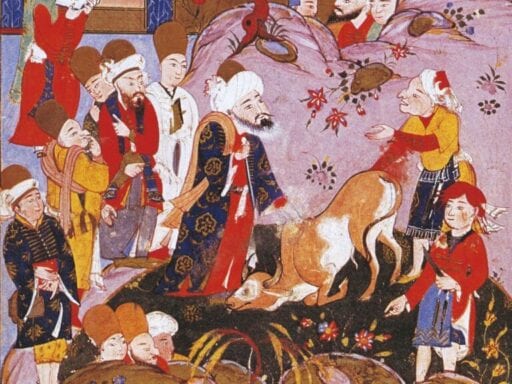

That’s how Omid Safi describes himself. A professor of Islamic studies at Duke University, he specializes in Muslim mystics, or Sufis, like the well-known poet Rumi.

Safi grew up in Iran, but he’s lived in the southern US for many years now, and he feels a deep affinity with leaders of the civil rights movement like Martin Luther King Jr. In fact, he sees certain parallels between their views and Sufi views on love and justice. He teaches courses on both sets of views.

I recently spoke with Safi for Future Perfect’s new limited-series podcast, The Way Through, which is all about mining the world’s rich philosophical and spiritual traditions for guidance that can help us through these challenging times.

Safi explained Sufism’s tradition of “radical love,” which involves both love for the divine and for our fellow humans, and what it would look like to be guided by that tradition today. What would Rumi do in a pandemic?

We also discussed how we might be able to lean into our suffering or solitude these days — how we can actually use it to our benefit, rather than trying in vain to escape it.

You can hear our entire conversation in the podcast here. A transcript of our conversation, edited for length and clarity, follows.

Subscribe to Future Perfect: The Way Through on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Sigal Samuel

Omid, I like to do thought experiments. Will you indulge me in one?

If Rumi were alive today in the US, living through the pandemic, what do you think he would be doing? Would he be engaging in petitionary prayer asking God to stop the coronavirus? Would he be out in the street delivering supplies to people? Would he be social distancing? Would he wear a mask?

Omid Safi

Well, I’m fairly certain that if he were to be in public, he would be wearing a mask. It’s just cruel and selfish to not wear a mask when you’re in public. It’s not just for your own sake, it’s also for the sake of everybody else. So let’s just get that one out of the way.

Look, we tend to have this dichotomy. Would he be praying, or would he be out on the street? Yes, both/and, all of the above! Where is it ever said that the life of the spirit and the life of bodies have to be divorced from one another? The God that is the subject of one’s petitions is the sustainer of our bodies, hearts, and souls. And what sets the path of radical love apart from so many other traditions is the notion that if you claim to love God, you have to love God’s creation. You cannot claim to be indifferent to the suffering of humanity and, indeed, other sentient beings if you claim to be on this path.

I think that’s what the message of Rumi and all these mystics would be today: to identify suffering, to stand with those who are hurting and vulnerable.

This is not a very popular thing to say: God does have a preferential treatment. But it is not for a religion. It is not for a nation. It is not for race or ethnicity or gender. It’s for the poor. God is on the side of the weak and vulnerable.

Sigal Samuel

I think in the context of the current pandemic, what we see is that Covid-19 is disproportionately taking the lives of Black people, people who are low-income, and people who are experiencing homelessness. So it would seem like these are the people that an ethic of love would demand that we really do our utmost to protect.

Omid Safi

Yet somehow among all the countries of the earth, we seem to be almost uniquely unable to rise to this challenge. Not because we lack the resources or the expertise. I wonder if we lack the care and the love.

Sigal Samuel

That reminds me of a stark contrast I see between a strand that you find in Sufi thought and a very prominent strand in American thought. In Sufism, we see a real emphasis on selflessness. And I don’t just mean being generous. I mean something much more radical: total ego annihilation, getting rid of your notion that you have a bounded self that is separate from others, separate from God. There’s this idea of al-fana, becoming completely absorbed in God.

To me, this seems like the polar opposite of American individualism. We’re in a country that has a very strong libertarian streak, where we’re almost obsessed with individual liberties. And I wonder if you think this emphasis on our personal freedom is actually getting in the way of expressing solidarity with one another during a pandemic.

Omid Safi

I do think that something about this rugged individualism is certainly both real and at times slightly exaggerated. I mean, after all, we are the very people whose founding document starts with “we, the people.” It doesn’t start with “I, the person.” There’s that notion of the peoplehood, that we-ness, which is so fundamental.

I was very blessed in my life to have been loved and mentored by the close friend of Dr. King’s Vincent Harding. And he would always take me back to that document and remind me that what that document says is “we, the people, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice.” He would say, thank God it never said “in order to form a perfect union.” Because we were not perfect when we committed genocide against Indigenous people. We were not perfect during the years of transatlantic slavery and Jim Crow. We are not perfect now. But the goal is to become just a little bit more perfect today than we were yesterday.

And how do we do it? Establish justice. Of course, justice is never individual. There’s a reason we call it social justice. It’s justice out in society.

Sigal Samuel

I hear you talking about two notions: love and justice. I’m curious how Sufi thinkers would say these two notions interrelate.

Omid Safi

Well, you’re very astute at picking that up, except they’re not two notions. They’re one notion. I almost fell out of my chair the first time I heard Vincent Harding express this because here was this 80-year-old Black Christian elder of the civil rights movement and it was as if he was reading something out of a Sufi text. The Sufis say that love is not an emotion. It is the very being of God unleashed onto this realm. So it’s helpful to think of this love as an oceanic wave that pours through you, and when it pours out of your heart, out into the public square, we recognize it as justice.

Dr. King and Ella Baker and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee members all said this in the civil rights era. All that we mean by justice is love when it comes into the public square.

Sigal Samuel

This reminds me of a Rumi quote that I read in a Coleman Barks translation: “What sort of person says that he or she wants to be polished and pure and then complains about being handled roughly. Love is a lawsuit where harsh evidence must be brought in. To settle the case, the judge must see evidence.”

There’s an interesting relationship there between love and justice, right? Love for your fellow people isn’t just saying to them, “Whatever you’re doing is great, universalism means total relativism, so if you want to be unkind or racist, that’s totally fine.” There is this element of judgment. There is this element of criticizing when you see something that you think is wrong or is going to harm other people. Being willing to criticize when you see that is part of justice. But that’s not separate from love.

Omid Safi

That’s right.

Sigal Samuel

Let’s talk about the massive suffering that a lot of people are experiencing during this pandemic. A lot of spiritual leaders are responding by trying to offer comfort that aims to ease the suffering. But there’s also this rich tradition in a lot of spiritualities about suffering actually being ennobling if you harness it correctly.

I see a lot of this attitude in Sufism. Rumi in particular says, “Brother, to be a lover, you must have pain. Where is your pain?” Elsewhere, he just says, “Seek pain, pain, pain!” He’s always calling upon us to increase our pain or suffering in some sense. So how would you invite us to think about this in relation to the pandemic?

Omid Safi

I think each of us has to be true to our own traditions. And I’m a Muslim boy. I’m not a Christian. So when I listen to Martin, whom I love, and I hear him talk about redemptive suffering — the willingness to bear suffering and to pick up our own cross, and that if we can do so with dignity, then nothing shall be more redemptive and transformative — I don’t know about that! Because that tradition of redemptive suffering isn’t mine.

As somebody who was pre-med in a previous life, I spent so many years volunteering in pediatric cancer wards. When I hear those kinds of Rumi quotes or hear Martin talking about redemptive suffering, I put myself in the situation of one of those young mothers at the hospital holding her 6-month-old infant and imagining what I would say to them. Would I go to them and say, “I know you’re enduring pain, I know your baby’s enduring pain, but I want you to know that this pain is redemptive?” No, I wouldn’t. And I don’t think any kind human being would. When you witness pain, sometimes the way of bearing witness is to actually be silent.

Now, what do I do with those traditions of Rumi talking about pain? To begin with, I don’t think we have to go looking for pain. There’s already pain in this world. Rumi begins his whole collection of poetry talking about the suffering that comes from all the different types of separations. For some people, especially nowadays, you might be separated from your loved ones. You might be separated from a place that feels like home. You might be separated from your own dreams — you thought you were going to be somebody and life hasn’t quite worked out that way. And there’s pain in that.

But then Rumi goes on to say, “Every heart breaks. But not every heart breaks open.” And there’s a difference between a heart that merely breaks and a heart that breaks open.

Sigal Samuel

First of all, thank you for saying that when someone is in a cancer ward or suffering terribly due to a pandemic-induced death, we don’t go up and say to them, “Everything happens for a reason; this is terrific!” I would feel terrible if someone said that to me.

What I’m left wondering is, how do we work with pain and heartbreak so that we become the person who as a result breaks open and doesn’t just break? How can we hold the suffering of the pandemic in a way that could actually be ennobling?

Omid Safi

I think a lot of it comes down to the idolatry of the finite ego. So many of us think that we end at the edge of our fingertips. But you are a fluid being. Your soul is extending and already enmeshed with other people. That same finite ego has a tendency to think that it is the master of the universe, that you write your own destiny. And so much of the pain that we have is the realization that our ability is finite, that we were unable to prevent pain for ourselves or for people that we love.

If instead we didn’t see ourself as one bounded self moving through and perhaps bumping up against other finite selves, but really saw one life, one soul, one yearning, one living, one love — then the suffering that we witness in somebody else and our own suffering would resonate with one another. I think that’s at least a key to a heart that breaks open.

Sigal Samuel

My first gut reaction when you were saying this was, no, this sounds horrible! Because if I feel that I’m actually this thing that merges with all other beings, then I share in everyone else’s suffering, and that multiplies my suffering a million-fold.

But my second response was, maybe that would help me feel a sense of connection with all these other beings. A big part of what is so painful when we’re suffering these days is that we feel alone in it. There’s something maybe psychologically calming about feeling like we are united with everyone else, even if the mode that we’re united with them in is a mode of suffering.

Omid Safi

Exactly. Rumi has this wonderful line: “You’re clutching with both hands to this myth of you and I. Our whole brokenness is because of this.”

We crave connection. That is an indication of the fact that we were never meant to be an island. We’re meant to be in communion with other beings. Rumi says, “You and I should live as if you and I never heard of a you and an I.”

Sigal Samuel

During the pandemic, though, a lot of us are in physical isolation. And I think a lot of us are so scared of being alone. There was a scientific study done a few years ago where they gave people the choice between being alone with their own thoughts for 15 minutes or getting electric shocks. And a lot of people chose the electric shocks!

But the Sufi tradition has a lot to say about the benefits of isolation, of khalwa. There is this idea that it can allow you to focus on meditation, on spiritual development. And this goes all the way back to the Quran and the Bible. You see Mohammed and Moses going for 40 days to the mountain to commune with God and then they get their big revelations. Is there some way in which we can use this pandemic to not run away from our isolation, but instead to lean into that solitude and somehow use it to our advantage?

Omid Safi

When you think about Moses and Jesus and Mohammed and the Buddha and Rumi and Ibn Arabi, all of whom did this practice of khalwa, of going to a cave or to a mountaintop — this wasn’t a permanent calling. It wasn’t that you would move to a cave. You would go inside to be alone with the One, and then you would come back and bring the fruits of that into society. I think that’s what I would love to see us as a world community do.

My hope is that this unplanned period of retreat can give us an opportunity to examine our own life, to think about what it is we’ve been prioritizing, what has been feeding our hearts. You know, so many of us are attached to our phone devices. We start to get really panicky when the battery light on them comes on because it means we only have 20 percent left. And then we nervously start looking around: Where’s my cord? Where’s my charger? Where’s the outlet?

Well, what if your heart had a red battery light? Would we even know where to go to recharge? That’s going to look different for every person. It might look like reading Rumi poetry. Listening to a great podcast. Gardening. Going for a hike in the mountains. Prayer. Yoga. I don’t particularly care what that practice is that rejuvenates your soul. But I think it is important to be asking ourselves: Do we know what it is? And do we know how to locate it? And do we know how to return to it again and again and again until it becomes a practice?

Sigal Samuel

Yes, I think that in the Before Times, many of us were so busy with a lot of things that distract us from our internal world. And, like you said, I hope that this pandemic can give some of us — I think it will be the privileged among us, really, who can afford it — a moment to look inward and reevaluate. So there is that period of khalwa, of retreat. But I like that you pointed out that there is this really dialectical relationship in Sufi thought between khalwa and jalwa: retreating into yourself and going out back into society.

Ibn Arabi, my favorite Sufi, says, “For him whom God has given understanding, retreat and society, khalwa and jalwa, are the same. In fact, it may be that society is more complete for a person and greater in benefit since through it at every instant one increases in knowledge of God.”

You want to have this period of isolation where you’re looking inward, but that’s not the end goal in itself. Ultimately, you want to use the wisdom you’ve gained in isolation and then go back out to other people and be able to see the Divine in them and interact with them in a better way.

Omid Safi

That’s exactly right. I think this notion of a khalwa, a retreat, is terrifying to so many people. Because who knows what you’re going find if you start looking into those unexamined corners of your own soul? What if you don’t like what you see?

But we all carry wounds. And just because you’re not looking at it doesn’t mean that it’s healing. So sometimes I think it can be very helpful to retreat.

And it’s not just wounds that you have in that unexamined portion of your soul. There’s also wonder and beauty and the presence of the One, whatever name you want to give to her or to him.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter and we’ll send you a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling the world’s biggest challenges — and how to get better at doing good.

Future Perfect is funded in part by individual contributions, grants, and sponsorships. Learn more here.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Sigal Samuel

Read More