“When you separate yourself from the day-to-day operations of a movement, you imagine the wrong questions that need to be answered.”

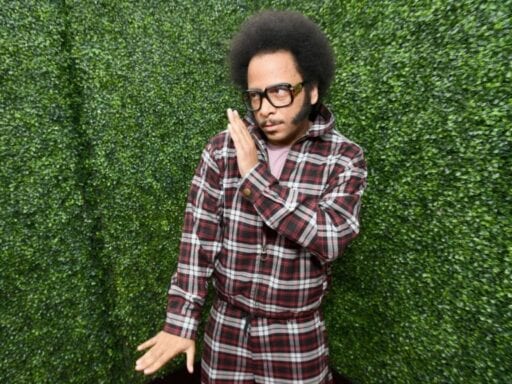

Boots Riley has combined activism and art for most of his career — as a rapper and frontman for The Coup, an organizer for the Occupy movement, and a lot more.

He’s also been working on Sorry to Bother You, his directorial debut, for a while. He finished the first version of the screenplay in 2012, near the end of President Barack Obama’s first term, and it was eventually published in 2014 in McSweeney’s. (You can buy that version.)

And after long years of trying to raise money to make the film, Riley finally pulled it off. Sorry to Bother You electrified crowds at its Sundance premiere in January. It’s one of the weirdest and most original movies of the year: part political satire, part comedy, part horror, and part something indefinable that’s all Boots. With a stellar cast led by Lakeith Stanfield, Tessa Thompson, Armie Hammer, Steven Yeun, and many more, it takes on race, code-switching, capitalism’s excesses, labor unions, and a lot more. It’s bound to confound some audiences and galvanize others. Which is, of course, what Riley wants.

I sat down with Riley a few weeks before the film’s theatrical opening to talk about his hopes for the film, its auspicious timing, and what he thinks about the relationship between activism and art.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Frazer Harrison/Getty Images for Sundance Institute

Frazer Harrison/Getty Images for Sundance InstituteAlissa Wilkinson

What I love about Sorry to Bother You is that it starts out feeling kind of realistic, and then it just becomes not realistic at all. I thought a lot about Michel Gondry (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, The Science of Sleep, Be Kind Rewind) while I was watching it, and then there was a joke in the film about Gondry.

Boots Riley

Yeah, and that joke is a declaration of war.

Alissa Wilkinson

Oh, yeah? In what way?

Boots Riley

Well, I wanted to give him a shout-out, so we originally had a stop-motion part that read “Michel Gondry.” Legally we didn’t have to get clearance to use his name. But I was like, “Hey, I don’t want to him hear about this and think I was dissing him.”

So I reached out to him so that I could play him the part and explain it. Also, I wanted to meet him!

So I go over to his office. My laptop isn’t working very well for some reason, because I have an old laptop, and it kept being jerky, but then I finally explained the story to him up to the point where I’m gonna play this clip of the stop-motion. But before I play it, he’s like [with French accent], “Wait, wait, okay. Please explain again. So, the richest man in the world, he can have anybody make a film that he wants, and he chooses me.” And I’m like, yeah. He’s like, “I like that.”

[Both laugh.]

Then, I play it, and he’s like, “Well … that’s not my style of animation.” I’m like, okay, nobody thinks it’s really you. But he’s like, “You know, someone might think that …” blah blah blah.

He pitched me, he said, “You should have me do it!” I was like, wow, that would be amazing. But one, Sundance is in two weeks, and two, we probably wouldn’t have enough money — you know, ’cause his joke was, “Pay me as much as [the film’s fictional CEO] Steve Lift would have paid me,” and I was like, “We probably wouldn’t have enough to pay you.”

“So,” I said, “how about we keep that there like it is and in the credits I’ll put ‘Michel Gondry had nothing to do with the making of this film.’”

And then he said, “Yes, but if people like it, then I look like an asshole. Like I missed the boat.”

I said, “How about if we said, ‘Michel Gondry had nothing to do with the making of this film, but he loves it.’”

He says, “Oh, yeah, yeah, that can be cool. Yes, let’s do that. Let’s do that.” To change that whole scene was going to cost another $10,000, and we had no more money left. So, he was all down, being really friendly.

Then as soon as I left, before I got back to the airport — I had flown here just for that — he had his people send a note saying, “Michel says no, and you have to change it.” I’m like, well we don’t legally have to, but his producers, and my producers, and it just got, you know …

I was like, “You could have just said that to me. Don’t wait until I leave.” So then we changed it, we just switched around the letters, and now it is a diss.

And I’m going to continue to diss him in each film until he answers me back.

Alissa Wilkinson

That’s kind of funny for this film, too, because it’s — well, would you call it an anti-capitalist film?

Boots Riley

Yeah, I’m down with it being called that. I don’t know what that actually means, but it has a critique of capitalism.

Alissa Wilkinson

And capitalism is a big part of the whole moviemaking enterprise.

Boots Riley

One of the main themes of the film is that you’re not going to change any of this by yourself. You’re not going to change it by making a cute art statement, you’re not going to change it by just figuring out how to be there, to do something that gives you more power on your own. You have to join with other people and make a movement.

Photo by Rich Polk/Getty Images for IMDb

Photo by Rich Polk/Getty Images for IMDbAlissa Wilkinson

In your role then as an artist, now in multiple media, how do you think about your place in activist movements?

Boots Riley

Well, in the immediate future, I hope this film can be used by organizers as an organizing tool, to get people to join organizations and be part of campaigns. If that happens, then, one, for me to stay relevant, I’ll need to connect with those movements. But I think then I’ll be okay with [having participated in the system] at that point. The whole movie is about the conflict going on in my head. They’re all different pieces of my brain.

Alissa Wilkinson

You started working on it a long time ago, right? In 2011?

Boots Riley

Yeah. Finished it in 2012 the first time.

Alissa Wilkinson

Which is the end of Obama’s first term. There will probably be people who see the movie and say, “It’s a product of the Trump age” — but it’s not.

Boots Riley

And what’s crazy — which people can see in the 2014 version that we published on McSweeney’s — so Omari Hardwick’s character, Mr. _______ (which is just “Mr.” and seven underscores), his line now is, “Worry Free is resurrecting America.” But it used to be, “Worry Free is making America great again.”

Alissa Wilkinson

Really? Wow.

Boots Riley

The real world made my script too on the nose.

Frazer Harrison/Getty Images

Frazer Harrison/Getty ImagesAlissa Wilkinson

That’s wild. Was there anything else like that?

Boots Riley

Yeah, like when I first wrote it … what we see in the film is there’s homeless camps all over the place in the middle of [Oakland]. When I wrote the movie, that wasn’t the case. There were homeless people, but they usually were able to find places out of sight. But with all the development, they have been kicked out, and so all that we showed was the actual homeless camps. Those didn’t exist when I wrote it, and now they do.

The other thing is the “Cola and Smile, Bitch” commercial. The McSweeney’s thing went out to 10 or 20,000 people, many of them quote-unquote creatives. I bet somebody that was working for the Pepsi commercial actually read that and put it in there.

I hope that nobody working for Trump read it and thought, “That’s actually good.”

Alissa Wilkinson

Well, I mean, that makes perfect sense. The movie is about systems in America that are just getting worse rather than better for the people caught inside of them — the cyclical nature that those systems have. I’ve always thought that “Make America Great Again” was genius marketing because it can mean whatever the person in power wants it to mean.

So the movie had a really long path to the big screen. Do you think there’s a reason that it finally came out when it did — that people were willing to invest in it now?

Boots Riley

You know, there’s a way to make an easy, poetic illustration of it, but in reality it’s not that. It’s little by little, getting certain things to happen.

When I finished writing it the first time, Lakeith Stanfield had not auditioned for his first film, and Ryan Coogler’s Fruitvale Station hadn’t been out yet. So during that time, it took getting different people on board to make other people okay to read it, and then getting Sundance on board, and getting various folks circling it with the money.

Some of the people who put in most of the money also did Fruitvale Station and Dope, and they made money off those things. That was Nina Yang Bongiovi and Forest Whitaker’s thing — their thing is to get directors of color, filmmakers of color to do stuff. Along the way, Jordan Peele was circling the project, but we were funded before Get Out came out. He had let me read that script, and I understood that it was gonna be something — I didn’t know it was going to be big as it was, but I knew it was going to be popular. I knew he was more popular than people knew. A lot of people in Hollywood didn’t understand how much people loved him. They were like, “Oh, it’s YouTube.”

Alissa Wilkinson

Yeah, he was huge even before Get Out!

Boots Riley

Yeah, so all of these things just kind of happened at the same time. Obviously our movie was already made before Black Panther came out — it had already premiered at Sundance — but all of these things were a confluence of things that happened in the milieu of these movements happening on the streets. There was Occupy. There is Black Lives Matter. All of these things are happening in the world: forces pushing people to make other choices, and art in the industry around it tries to respond to that.

Doug Emmett/Sundance Institute

Doug Emmett/Sundance InstituteAlissa Wilkinson

Art can influence movements, too, right? Does art influence movements or do movements influence art, or is it a cycle? You’ve been at this so long, how do you think about that?

Boots Riley

Yeah, it is cyclical. I think that sometimes art ignores a movement, or art thinks it’s responding to a movement. There’s a book called 9.5 Theses on Art and Class, by an art critic [Ben Davis]. He has a bunch of illustrations that show how artists really want to respond to what’s going on, and respond to a movement.

But because when you live the quote-unquote artist life and separate yourself from the day-to-day operations of a movement — like getting people out to do things — you imagine the wrong questions that need to be answered.

People involved in a movement can tell you something different. One example that he had was about this art show that happened here [in New York City], an installation art show during the Iraq War that he walked through. There’s all these people, blood, and guts, and all this kind of stuff, because the artist’s idea was, “Hey, if people just knew how bad war was …” That people just don’t understand how bad it is.

But people that were organizing the anti-war movement understood: It’s not that people didn’t think that it was bad, they just thought there wasn’t anything they could do about it. So his question should have been different. The question he was answering should have been different.

So sometimes the relationship between art and movements can be cyclical in the wrong way, a way that actually takes things off track. I think that’s kind of what film has done for many years. It’s answered the wrong questions, not the ones that people organizing movements want to see happen.

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png