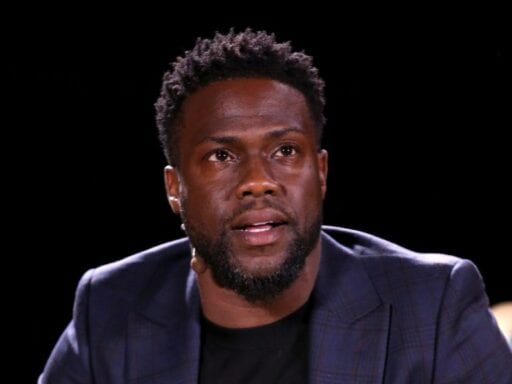

Kevin Hart’s Oscars downfall reminds us that not all internet backlashes are the same, no matter how much he and Ellen DeGeneres dismiss “haters” and “trolls.”

Despite his best efforts, the continuing controversy around Kevin Hart’s decision to withdraw from hosting the 2019 Oscars has done what he claimed he didn’t want it to do when he stepped down — create ongoing distraction and debate.

The latest debate cycle on social media has come thanks to Ellen DeGeneres’s controversial attempt to convince Hart to resume his hosting gig, which he walked away from in December after backlash arose over homophobic jokes he’d made in years past. The backlash followed Hart’s announcement that he would host the 91st Academy Awards in February, which prompted a wave of outrage as the queer community surfaced a history of comedy routines and tweets in which Hart had repeatedly joked about trying to prevent his son from becoming gay — among other instances of homophobic humor.

Initially defiant, Hart refused to apologize for the jokes and tweets in an Instagram post that referred to those who were angry as “trolls,” and claimed he’d already apologized. “I’ve addressed it,” he said, sounding frustrated. “I’ve said where the rights and wrongs were. … I’m not going to continue to tap into the past when I’ve moved on and I’m in a completely different space in my life.”

After the Instagram post, Hart ultimately issued an abrupt about-face, tweeting, “I sincerely apologize to the LGBTQ community for my insensitive words from my past” and noting that he was stepping down from the gig so that he wouldn’t “be a distraction on a night that should be celebrated by so many amazing talented artists.”

But DeGeneres, a personal friend of Hart’s and a former Oscar host herself, wanted him to reconsider. In the January 4 episode of her syndicated daytime talk show, DeGeneres revealed that she had called organizers within the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, who reportedly told her they still want Hart to host.

DeGeneres and Hart then had a conversation about the controversy, in which both asserted that the people who were angry about Hart’s history of homophobic comedy were “trolls.”

“There are so many haters out there,” DeGeneres told Hart at one point. “Whatever is going on on the internet, don’t pay attention to them. That’s a small group of people being very, very loud.”

DeGeneres also declared that Hart had grown since his homophobic humor from 2012, and agreed with Hart’s own assertion that anger over his past was “an attempt to end me,” and that “Somebody has to take a stand against the … trolls.”

“Don’t let these people win,” DeGeneres told Hart. “Host the Oscars.”

DeGeneres and Hart both portrayed the backlash as being the same type of social media “mob justice” that other prominent celebrities and media figures faced throughout 2018 — most notably James Gunn, Sarah Jeong, Dan Harmon, and Roseanne Barr.

But while it’s tempting to lump all of these incidents together as part of a trend that uses social media as a weapon to manufacture outrage on an increasingly polarized internet, there are several major, if subtle, differences at work between Hart and each of the other public figures who came under fire in 2018 for “comedy” gone wrong. There are also several similarities worth noting — including how the notions of “comedy,” “satire,” and “punching up” versus “punching down” all contributed to different outcomes for each of those figures.

While it’s easy to see Hart’s predicament as a result of internet mob justice, that’s a drastic oversimplification. A “troll” is a specific type of internet abuser who uses callous harassment to target victims, often illogically and with the intent to cause emotional distress. But plenty of internet anger comes from real people who are not trolls — and even though anger on social media often takes a collective shape, not every internet “mob” is the same.

More importantly, this reduction dismisses the real cruelty inherent in Hart’s old comedy rhetoric, while blaming the targets of that cruelty — queer people — for pointing it out. It also overlooks how Hart’s response to being called out made a bad situation worse, wasting what could have been a moment to create more empathy out of pain.

What’s so different about each of these incidents? For one thing, the direction of the “punch.”

Earlier in 2018, former Guardians of the Galaxy director James Gunn and tech journalist Sarah Jeong, respectively, were each accused of making deeply offensive statements on social media. Their reaction and response gives us a clue to the context at work during each of their respective public “shamings.”

Gunn lost his high-profile job in July 2018 after right-wing trolls and Gamergaters pelted Marvel and its parent company Disney with “outrage” over pedophilia jokes that Gunn had made on Twitter several years earlier, between 2009 and 2012. Then, less than two weeks later, Jeong — who had just been announced as joining the New York Times op-ed staff — was attacked for her long history of irreverent “I hate white people” humor on Twitter.

The ire that swirled around Jeong was deeply intense, and arguably far more widespread than the anger directed at Gunn. While Gunn’s tweets mostly generated outrage among a right-wing minority, Jeong’s tweets also provoked a wider discussion about whether it’s possible to be racist against white people, and the difference between comedy that “punches up” verses comedy that “punches down.”

Both Gunn and Jeong were attempting various forms of satire. Gunn was attempting shock humor in a juvenile South Park style; Jeong was attempting to satirize the bigoted, hyperbolically hateful language that, as a female tech journalist of Asian descent, she regularly experienced at the hands of hateful trolls. In both cases, the average onlooker, confronted with only the offensive joke and none of the context, might be well within their rights to walk away confused or even angry. But in both cases, the overall comportment and career directions of both Gunn and Jeong supported the sincerity of the apologies they eventually issued.

Like Gunn and Jeong, Hart says he was attempting to be satirical. In a 2015 Rolling Stone profile, he discussed a homophobic joke that he’d included in his 2010 stand-up special Seriously Funny. In the act, Hart stated, “One of my biggest fears is my son growing up and being gay … If I can prevent my son from being gay, I will.” He seemed to echo this sentiment on Twitter on several occasions between 2009 and 2012, at one point “joking” about hitting his son over the head with his daughter’s dollhouse if he ever caught his son playing with it.

As he told Rolling Stone in 2015, Hart intended these jokes to constitute a self-deprecating look at his own bigotry and fears: In essence, the humor was supposed to lie in the level of absurdity he was displaying as a straight man who was insecure about his masculinity. “The funny thing within that joke is it’s me getting mad at my son because of my own insecurities,” he stated. “I panicked. It has nothing to do with him, it’s about me.”

The problem is that not everyone in Hart’s audience read the joke as mocking Hart, rather than mocking queer identity itself. That’s because the kind of gay panic that Hart was joking about is very real, and it isn’t funny to the real queer people who have to bear the potentially dangerous and devastating impact of such fear in the real world.

Hart himself seemed to manifest that gay panic offstage. In 2009, he had turned down a role in Tropic Thunder because the character was gay, expressing reservations about playing such a “flagrant” expression of queerness. Even in his attempt to explain his Seriously Funny set to Rolling Stone years later, he expressed the very definition of homophobia: “It’s about my fear. I’m thinking about what I did as a dad, did I do something wrong, and if I did, what was it?”

Many of us have jokes/tweets we regret. I’m ok with tasteless jokes, depending on context. What bothers me about these is you can tell its not just a joke-there’s real truth, anger & fear behind these. I hope Kevin’s thinking has evolved since 2011. https://t.co/U1YgnCyByt

— billy eichner (@billyeichner) December 6, 2018

So when Hart made those comments, he wasn’t effectively calling out the absurdity of straight male insecurity, but rather reinforcing a homophobic view of queer identity as something shameful and fear-inducing.

This is the basic concept behind the idea of “punching down” in comedy versus “punching up.” When comedians punch up, they’re hitting back against people with more power, privilege, and social standing than they have — in essence, they’re going after people who are insulated from harmful real-world effects that might result from their humor. This is essentially why Jeong’s tweets had no real-world effect: There’s no systemic way in which racism manifests against white people, and no real-world tradition in which marginalized groups have acted out racially motivated violence against white people. Her satire was punching up.

By the same token, we might say that Gunn’s ill-considered jokes about child rape didn’t really punch in any direction except, perhaps, sideways. The dozen or so old tweets uncovered and circulated by right-wing pundits were largely directionless — too ill-formed to be anything but juvenile shock humor. This is probably why Gunn was the first to admit under pressure that the jokes were, first and foremost, really bad.

Whenever a comedian punches down, however — for example, when they base an entire joke around the idea that being gay is harmful, shameful, and deserving of physical violence in response — they contribute to and further reinforce actual real-world beliefs and stereotypes. And usually, the resulting harm falls upon the most marginalized and vulnerable members of society, people who bear the physical brunt of ideas that may seem like humor, but which, in actuality, help spread fear-mongering, bigotry, and cruelty — as other comedians like Hannah Gadsby have made all too clear.

So it didn’t really matter that Hart’s tweets were old; his humor, many agreed, overwhelmingly punched down. And the fact that he eventually stopped making those sorts of gay jokes — overt homophobia never resurfaced in his standup sets following 2010, and the offensive Twitter references seemed to disappear after 2012 — indicates that on some level, he had at least come to know better.

What Hart didn’t do, however, was just say as much when people called him on it — thereby making the whole situation worse.

Another major factor in who survives a shaming? The attitude of the shamed — and the level of commitment to the “joke.”

How each of 2018’s “shamed” figures reacted to their shaming also had a lot to do with the overall outcome of their situation.

In response to the right-wing outrage against him, Gunn apologized honestly, admitting that his jokes were bad and stating that he now tries “to root my work in love and connection and less in anger.” It wasn’t enough to stop his ousting from the Guardians franchise, but he subsequently landed a new, equally cushy role as director of the next Suicide Squad.

Jeong also apologized. When she did so, she made it clear that the particular brand of humor she had engaged in was a measure of countertrolling in response to perpetual online harassment hurled at her by racist and misogynistic trolls, members of the alt-right, and others who hailed from toxic corners of the internet. “I can understand how hurtful these posts are out of context,” she wrote, “and would not do it again.” The New York Times said it understood, and stood by its hiring of her.

Hart, however, refused to apologize — and has done so consistently over the years. In December, as many people demanded that Hart discuss what he’d said in the past and outlined the harmful message the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was sending by inviting him to host, he remained defiant, revealing via Instagram that the Academy had called to ask for his apology — and that he was refusing to issue one.

“I’ve addressed it,” he said, sounding frustrated. “I’ve said where the rights and wrongs were. … I’m not going to continue to tap into the past when I’ve moved on and I’m in a completely different space in my life.”

Hart repeated this stance on The Ellen Show on January 4, speaking at length about how he had apologized in the past, and has been frustrated by what he feels is widespread lack of acknowledgement of his apologies:

I know who I am. I know that I don’t have a homophobic bone in my body. I know that I’ve addressed it, I know that I’ve apologized. I know that within my apologies, I’ve taken 10 years to put my apology to work. I’ve yet to go back to that version of the immature comedian I once was. … Nobody is saying, “Guys, this is 10 years.” No headlines are saying, “10 years ago, he apologized.” Nobody’s finding the apologies. Nobody’s finding the footage from where I had to address it. I had to address it when I did Get Hard promo with Will Ferrell, because of my joke that I had about my son. I had to address those tweets in 2012, at a very, very heavy junket, where I was asked questions about homophobia based on those tweets, and I had to address it and apologize, and say I understand what those words do and how they hurt. I understand why people would be upset, which is why I made the choice to not use them anymore. I don’t joke like that anymore, because that was wrong. That was a guy that was just looking for laughs, and that was stupid. I don’t do that anymore. So to be put in a position where I was given an ultimatum, “Kevin, apologize or we’re going to have to find another host.” When I was given that ultimatum, this is now becoming like a cloud. What was once the brightest star, and brightest light ever, just got a little dark.

But while Hart has indeed addressed the jokes in the past, he hasn’t exactly apologized for them, at least not publicly. “I wouldn’t tell that joke today,” he said in the 2015 Rolling Stone profile, “because when I said it, the times weren’t as sensitive as they are now. I think we love to make big deals out of things that aren’t necessarily big deals, because we can. These things become public spectacles. So why set yourself up for failure?”

That same year, HitFix’s Louis Virtel challenged Hart and Ferrell on homophobic humor in the film Get Hard. In a scene from the film, the two enact a stereotyped version of homosexuality as a form of prison yard humor. Hart explicitly didn’t apologize for the scene, instead describing the joke as “funny is funny.” Hart implied that the reason the scene was included in the film was that the homophobia fit his character. “When doing it, I felt that the scene called for the actions and reactions that we gave … I just look for the laugh.”

In the two days that elapsed between his announcement as 2019 Oscars host and his apparent resignation from the job, Hart stuck by this code of silence. And as many of his old tweets were resurfaced and heavily criticized during that time, Hart initially tried to delete them rather than discuss them.

I wonder when Kevin Hart is gonna start deleting all his old tweets pic.twitter.com/ZbYG6SI3Xm

— Benjamin Lee (@benfraserlee) December 5, 2018

Again, Hart’s reluctance to engage the debate around his tweets stems back years. When the December controversy unfolded, the author of the 2015 Rolling Stone profile, Jonah Weiner, circulated portions of the full interview transcript, including on-the-record remarks which hadn’t been published in the piece. In it, as Weiner revealed on Twitter, Hart explicitly stated that he did not want to apologize for his old tweets.

“I’d never apologize for what was never intended to be disrespectful,” Hart told Weiner. “I’d never allow the public to win for something I know wasn’t malicious.”

But reading Hart’s tweets, it’s hard to agree with his point of view that they aren’t disrespectful, regardless of his intent. The tweets don’t exactly suggest that Hart had suffered a one-off lapse in judgment in his 2010 comedy special; they included a litany of homophobic slurs and a reference to another comedian as “a gay billboard for AIDS.” While Hart professed to Rolling Stone that he had been peddling a more sophisticated level of irony in his standup, these tweeted slurs and stereotypes were straightforwardly homophobic, far from being defensible as satire.

This is where Hart’s humor bears some affinity to the alleged “humor” of Roseanne Barr, whose racist comment on social media about former White House staffer Valerie Jarrett led to ABC’s cancelation, earlier in 2018, of her hit Roseanne revival.

Barr’s comment referencing an ethnic slur against Jarrett wasn’t an ancient contextless tweet, but rather a new one, and an extension of racist views she’d aired throughout her career and as part of her online presence for years. Hart’s humor, likewise, was an extension of gay panic he’d evinced, and slurs he’d deployed, both in his standup and on social media, for a long time. No matter what you think of Hart’s comedy as a whole, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that he actually does wrestle with homophobic views and a belief in harmful and hurtful stereotypes.

Like Barr, his defensiveness and reluctance to apologize made the entire situation look worse for him than it otherwise would have.

It’s easy to rail against “internet mobs,” but not every backlash is the same

“With social media, we’ve created a stage for constant artificial high drama,” Jon Ronson wrote in his 2015 book So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed.

Ronson’s book itself was publicly shamed for heaping too much shame upon shamers. But there’s a modicum of truth in this idea: In the age of social media, many groups, especially alt-right subcultures, have learned how to weaponize social media, memes, bots, and other online tools to amplify their message and even the appearance of backlash itself. Sometimes, the amount of public shame that appears to be occurring is fundamentally deceptive, bolstered by trolls and bots to amplify fake outrage.

In the current online environment, where things are often artificially ramped up to 11, it’s incredibly easy to write off every wave of social media backlash as an overreaction.

But there’s a problem with Ronson’s argument that social media is essentially turning us all into sociopaths who care “more about ideology than they do about people.” It ignores all the ways in which online words can do real-world damage.

Oh, sure, social media backlash can have immediate, devastating, and even career-ending effects for anyone who who faces it. And en route to his ultimate apology, Hart was quick to categorize the backlash against him as being driven by “angry people,” as though it was just his noble misfortune to be caught up in an internet outrage cycle. As one journalist noted, Hart made the outcry over his homophobic jokes all about himself:

Kevin Hart has a massive platform and he could have turned this entire mess into a teaching moment about casual homophobia. Instead, he made it all about him, and now angry people are even angrier about “PC culture” and “SJWs.” Just a shame all around.

— Dana Schwartz (@DanaSchwartzzz) December 7, 2018

It’s not that Hart doesn’t have a point: Yes, outrage cycles are painful. But the worry over the individual who’s set off an outrage cycle, inadvertently or otherwise, often upstages the real issue. Anger doesn’t arise out of spite or personality flaws; people typically don’t get angry for their own entertainment (unless they’re trolls). Real, genuine anger arises from hurt and the need to create change.

When commentators like Ronson or Hart attempt to reduce online outrage cycles to empty or trumped-up dramas, they diminish the validity of anger as a tool for creating change. They diminish the crucial, vital ways in which social media has given a voice to people who haven’t previously had a way to express their anger this easily or loudly. They dehumanize everyone who’s ever needed to rely on their anger to find the courage to say, simply, “What you’re doing hurts me and puts me in danger of encountering more hate and cruelty.”

In this case, Hart didn’t get accidentally caught up in a maelstrom driven by angry people. He practiced a consistent form of comedy rhetoric that hurt queer people.

He punched down, joking that giving his son a head injury was a preferable alternative to letting the child potentially grow up gay. His jokes made the world more dangerous for queer people. Hart’s eagerness to blame “angry people” and subsequent reluctance to just say, “Wow, those were shitty jokes that hurt people and I never should have made them to begin with” made the world a more dangerous place for, well, everybody.

Author: Aja Romano

Read More