As the Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic spreads around the globe, “our biggest enemy is panic,” Brooks says.

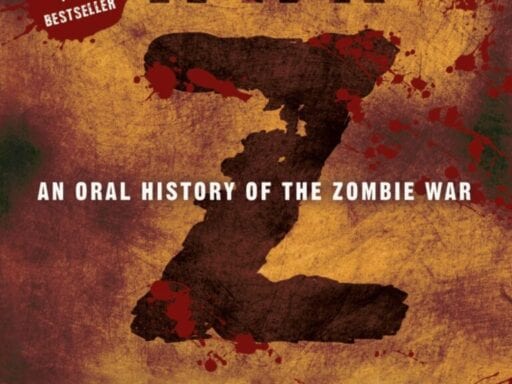

In 2006, author Max Brooks published World War Z, an “oral history” of the world following an apocalypse in which a highly infectious fictional virus called Solanum first pops up in China then spreads across the world, turning scores of people into zombies. (Three years earlier, Brooks had published The Zombie Survival Guide, a “humorous” guide to surviving the zombie apocalypse, and the fictional journalist performing the “interviews” that make up World War Z is also named Max Brooks.)

World War Z was adapted into a movie in 2013, starring Brad Pitt as a man who manages to essentially save the world from a zombie apocalypse. But the novel is much better, and beloved among zombie enthusiasts and foreign policy wonks alike for the way it shows how different cultural factors shape different countries’ responses to the virus and how those responses play out in the face of a global pandemic.

Now, faced with the Covid-19 pandemic (which is not quite as severe as the one caused by Solanum), I haven’t been able to stop thinking about World War Z. The parallels between Brooks’s novel and our reality are eerie, from China trying to cover up the spread of the virus early on to a US-based outbreak occurring just 45 minutes north of New York City to opportunists hawking a fake cure to the American response being slowed due to the virus emerging during an election year — and that’s just the beginning.

So I called up Brooks, who was at home in California, to talk about his book, American history, and what needs to be done right now. We spoke on March 13, one of the biggest days yet for a wave of pandemic-related closures and suspensions of businesses, institutions, sports, schools, and more in the US.

Alissa Wilkinson

You’ve been watching what’s going on. What have you been thinking?

Max Brooks

[Sigh.] Well, I mean, I think, at this point, today, our biggest enemy is panic because we’re reaching that mass psychological tipping point. We’ve been in denial too long, and panic is the fruit of denial. That’s not just society — that’s individuals. When you stick your head in the sand and you deny something, and you keep denying it long enough, then suddenly you get caught up in the problem and you’re not prepared for the problem, that’s when you panic. I’m starting to see that, and that is very scary. Panic is the one thing we do not need right now. If there was ever a time for clarity and facts, this is it.

Alissa Wilkinson

In World War Z, there’s the outbreak that causes people to become zombies, but then there’s something called the “Great Panic,” when people start to freak out and take drastic measures, like heading north because they’ve heard that the zombies can’t survive the cold. Different countries experience the Great Panic at different times. But according to the book, more people die from the panic than the actual infection.

Max Brooks

Unfortunately, that happens in many crises. People lose their minds and they do irrational things and they hurt each other. You don’t want that to happen. You’ve got to make sure you keep your head when things appear dark all around you. Because, No. 1, you can’t fix the problem if you’re too busy losing your mind. Then you have what’s called second- and third-order effects, where other people start to get hurt. I’m starting to see that with panic buying. So far there hasn’t been a lot of violence, which is great, and I hope it never happens. But the mass run on things like bottled water — in a pandemic, the water is going to keep running. It’s not an earthquake.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19811571/1212787189.jpg.jpg) Chesnot/Getty Images

Chesnot/Getty ImagesAlissa Wilkinson

I think we’re mostly used to only preparing for weather events, like hurricanes or blizzards, where you might lose basic services like water and electricity. It doesn’t feel like we as a culture have any idea how to deal with inconvenience as a main result of a mass occurrence such as this.

Max Brooks

No. And this is a huge problem. This started at the end of the Cold War, and it’s been accelerating. We have been gutting our resilience to fund our comfort.

I’ve seen some huge milestones along the way. I think one of the biggest ones was in the darkest days of the Iraq War, when the world was crying out for an alternative to petroleum. People were dying by the thousands in Iraq — Americans and Iraqis — and the global economy was teetering, all because of this one substance that we had addicted ourselves to. If there was ever a time for the great minds of science and industry to break our addiction, that was it. Instead, we got rock star Steve Jobs crowing about watching The Office on his new iPhone.

We see this massive divorce between science and current events. You saw it in the medical sector. I remember in the mid-90s, everyone was talking about genetic cures — you know, these targeted genetic wonder cures. They were right around the corner. They were five years away, 10 years away.

Well, my mother died waiting for one, and I’ve got two friends with Parkinson’s disease that are still waiting for them, and as far as I know, the greatest medical breakthrough of the turn of the century was a blue pill to make baby boomers’ dicks hard. That was it.

Alissa Wilkinson

What accounts for that divorce between science and current events?

Max Brooks

I think for 50 years, way before the end of the Cold War, we have been divorcing ourselves from the systems that keep us safe. We’ve been increasingly taking safety and security for granted, and that’s a long march. We’ve been doing that since the end of World War II.

We’re at a point now where today’s average grandparents grew up vaccinated. So they don’t have the same gut fear of disease of the generation before, who used to be killed or crippled by plagues. The average grandparent grew up with indoor plumbing and electricity and television, and the assumption that they were going to get a good job and get a car and live a good life. That assumption has become entitlement.

We have become victims of our own success because what we call disaster prepping now, they used to just call poverty in my grandparents’ days. The idea was that you’ve got to can stuff, you’ve got to pour a little water in the grape juice to make it last — not because you’re preparing for the end of the world but because you knew hard times would happen. You always kept that in the back of your mind.

We’ve totally forgotten that. And look what’s happening right now.

Alissa Wilkinson

I’ve been talking with friends who’ve had a really hard time convincing their parents that they should take measures to protect themselves and others from the spread of the virus. And obviously lots of people have been out at restaurants and bars despite the urgency, demonstrated by news out of Italy, of staying apart and trying to contain that spread. Is this behavior a symptom of this forgetting that you’re talking about?

Max Brooks

I think we’re all to blame. I think every generation is to blame … I’m entitled to something, and somebody else is taking it away, and my guy is going to beat them up and get it back from them. The color of the message changes, the generation that believes in the message changes, but it’s still basically the same message: I deserve more than what I’ve got, and someone else is taking it from me, and I’m not going to take that anymore. That, I think, transcends political boundaries and generations. I think our sense of entitlement is strong and powerful now.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19811575/1212768010.jpg.jpg) Alex Wong/Getty Images

Alex Wong/Getty ImagesAlissa Wilkinson

Of course, you can’t beat up your enemy if your enemy is a virus.

Max Brooks

You can’t. A virus doesn’t care about your political parties. It doesn’t care what God you pray to. It sure doesn’t care which bathroom you use — but it does care if the bathroom is hygienic.

Alissa Wilkinson

There’s a bit in World War Z where someone is saying that in war, your best weapon is fear. But you can’t wield fear against an enemy that doesn’t feel it, like a virus.

Max Brooks

So much of war is psychological. So much of war is trying to scare the hell out of the enemy. That’s literally one of the main reasons we fought Desert Storm. We wanted this big, massive World War II-style war on cable news basically to say to the world, “Don’t mess with us because we’ll destroy you.” That’s deterrence. Deterrence is part of warfare.

But you can’t deter an enemy that is immune to fear. You can’t scare a virus. You can’t negotiate with a virus. You can’t make a separate peace with a virus. A virus has a biological imperative, which is to infect and spread.

Alissa Wilkinson

In US media coverage, do you see attempts to frame this threat as a certain type of enemy that can be defeated?

Max Brooks

I think we haven’t had our priorities straight for a little while. We were worried about crashing the economy, and we were worried about scoring political points.

All of these terrible, terrible trends that we’ve been sowing for so long are coming back to haunt us right at this minute. People listen to different news sources, cultural divisions, people not trusting in institutions anymore. It started on the left in the ’60s and then was adopted by the right in the ’80s, and now neither side trusts the middle, the grown-ups, the institutions that keep us safe.

As a result, we don’t have a single unified voice for reason and for instruction the way we did in the plague of my generation, AIDS. In the 1980s, you had one voice, you had [US Surgeon General] C. Everett Koop. You didn’t have Reagan. You didn’t have political commentaries. You had the surgeon general, and he was the authority, and you listened to him and you respected him and you followed his instructions, and as a result, we stopped AIDS. We stopped it with public education. We didn’t stop it with a cure. We still don’t have a cure. We still don’t have a vaccine. But we managed to hold back a disease that could have infected the world.

Alissa Wilkinson

Do you think Americans are capable of following orders in the way other countries have done to stem the tide, or have we already crossed the point of no return?

Max Brooks

Oh, no, I think it’s very possible. American culture has always had strengths and weaknesses, and one of our weaknesses has always been putting our head in the sand. Not reacting to coronavirus — that’s just the latest one — but 9/11, Sputnik, Pearl Harbor … Americans are always the worst at proactive response. That’s our weakness.

But the great thing about America is we are, I think, the most culturally flexible people in world history. We are really good at reinventing ourselves and doing what we have to do when we have a clear direction. Nobody does better than America when it comes to that. I do think we totally have within our means the power to turn this around.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19811582/1207376452.jpg.jpg) Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu Agency via Getty ImagesAlissa Wilkinson

At what other points in American history have we done that?

Max Brooks

You see it throughout American history. In World War I, the government really had a fear: How can we go to war against Germany when the two largest ethnic groups in this country are Irish and Germans? You’re going to ask millions of Irish Americans to take up arms and fight alongside the British Empire, especially when the British Empire has just executed IRA rebels? You’re really going to ask German Americans to pick up guns and point them at what could be their own family? That was a real fear. But it never came about.

In World War II, you see the exact same thing. Our enemies believed that, as a heterogeneous culture, we would shatter when attacked and everybody would turn on each other. And we didn’t.

Every culture in this country all came together, even ones who you wouldn’t have blamed for not coming together. Would you really blame Native Americans for not fighting for this country? And yet, they were magnificent — they were the Navajo Code Talkers, and they were spectacular warriors on the battlefield. If you look at the history of Native Americans who fought in World War II, it’s just medal after medal, valor after valor. You look at black troops: Why would they want to fight, given Jim Crow back home? And yet, as in World War I, many black Americans were magnificent warriors — Tuskegee Airmen, Red Ball Express, an all-black tank division that fought under Patton.

And of everyone, Japanese Americans, whose family members were literally being put in internment camps. And yet they believed so strongly in the ideal of America that they became the 442nd Infantry Regiment and fought all through Europe and defeated the Nazis.

We did it in the Space Race, where we were far behind the Soviets, and we came together and invested in science and technology, all the way down to the schools, and we jumped ahead of them and got to the moon.

You saw it after 9/11. It was a failure of the government to only tell us to pray, hug our kids, and participate in the economy. Americans were ready to do anything asked of them. I think if the government had said, “Listen, it’s time for a gasoline tax, there’s no two ways about it,” we would have done it. We would have sacrificed.

I see it over and over again. We’re talking about a country whose last president could have been a slave of our first president. I dare you to show me any other civilization in world history that has made that much social progress in that short of time. I really do think there is not a problem that exists that Americans cannot conquer.

Alissa Wilkinson

In this case, if you were in charge or advising the president how to proceed, what would be the best-case scenario? What should we be doing?

Max Brooks

It’s very simple. You appoint a single voice, and then what that voice communicates is dictated by facts — the facts on the ground, science, public health. That voice tells the American people what is happening and what they should be doing about it. You start with that.

That voice probably should not be the president. Ronald Reagan was smart to give it to C. Everett Koop. We need a C. Everett Koop. That’s the person who needs to be on TV making addresses and tweeting and going on social media telling us what to do, backed up by facts.

From that point on, you let the facts dictate where we divert our resources. Is it to shutting borders? Is it to test kits? Is it to funding hospitals and training emergency workers? Is it all of them?

But the first thing you’ve got to do is listen to the qualified experts and then have a unified, single voice and face communicating those experts’ findings to the public. That’s how you do it. That’s how you beat this thing.

Alissa Wilkinson

One interesting parallel between World War Z and what’s happening now is that in your story, the US government is also slow to take action because it’s an election year, and they don’t want their response to affect the election. How is the fact that we’re in an election year playing out here?

Max Brooks

I think it makes everything worse. I think it clouds people’s judgments. I think they’re always looking for a political boogeyman behind everything. I think it erodes public trust when we’re in an election year, because you smell politics behind everything.

Trust is the one thing we need now more than anything. And I don’t mean trusting in our leaders; I mean trusting in the facts, trusting in the qualified experts.

America was very divided in the 1980s between the right and the left, but we eventually came together on AIDS. The right had to give up their social and cultural prejudices, not seeing this as just a gay disease or God’s punishment or all that horrible bullshit. The right had to move past it. The left had to move past free love — and that is a tremendous cultural swing, to go from free love to safe sex. I was an early adolescent, and we had AIDS week at our school, educating us about how you could get it, how you could stop it. As a country, we had to completely change our culture in order to fight this thing.

Alissa Wilkinson

It does feel like one of the challenges is tapping into people’s empathy and compassion for people who aren’t them — the idea that I am not likely to die, but there are other people who I need to be thinking about, people who are vulnerable.

Max Brooks

That’s a huge one. It needs to be addressed publicly and clearly. It’s not just about you getting infected, it’s about who you can infect. You need to worry about the people around you who you might infect, and you have to worry about second- and third-degree effects. You may not know anyone who’s immunocompromised, but what if you know someone who knows someone?

The greatest example I can ever think of, ironically, was on a comedy show in the 1980s. On Robert Townsend and His Partners in Crime on HBO, Robert is about to get in bed with a woman, and he goes, “Huh, but I don’t have a condom. What should I do?” And then poof, C. Everett Koop — the real guy! — poofs into the room. He says, “C. Everett Koop, what should I do?” and C. Everett Koop says, “Listen, Robert, you need to understand, when you’re having sex with her, you’re having sex with all of her sexual partners.” He does a little I Dream of Jeannie finger and then poof, 12 guys appear in the room. It brings the whole thing home.

We need something like that in a million different versions — a funny version, a comic book version, any way we can get the message across that there’s a chain of transmission, and anyone you infect might eventually infect someone who could die.

(Four days after our conversation, Max posted the following video to his Twitter account:)

A message from me and my dad, @Melbrooks. #coronavirus #DontBeASpreader pic.twitter.com/Hqhc4fFXbe

— Max Brooks (@maxbrooksauthor) March 16, 2020

Alissa Wilkinson

I wrote a book on the apocalypse and pop culture, which was published shortly before the 2016 election. One thing we talk about in it is that historically speaking, apocalypses are understood to be “revelatory” moments. The apocalypse is not so much the end of the world as a moment when reality reveals itself to us. In an apocalypse, we understand in a new way what human nature is like, what lies beneath the thin veneer of civilization, what we value, what we think is important.

Your book focuses on this by showing how different countries respond to the threat of a zombie apocalypse — which is basically a pandemic. Now we’re seeing it happen in front of us. What have you seen?

Max Brooks

I think different cultures respond in different ways. Different cultures have different political systems, which definitely affects how they respond.

I think the sharpest contrast is between the US and China. Everything that goes wrong in China with this virus is directly laid at the feet of Xi Jinping. He has all the power, so he has all the responsibility. Every death is on his hands.

But, by the same token, we are responsible for our own deaths in this country. If we don’t like our leaders — well then, look in the mirror; we put them there. We voted for them. If we don’t like the way the CDC is handling this virus, well, who voted to defund the CDC? Who didn’t listen to the cries of health professionals saying, “Wait a minute, they’re defunding the CDC!”? We didn’t listen. We were like, “Oh my God. Friends is on Netflix. I have bingeing to do! I have things! There’s an app where I can put bunny ears on myself and send it out!”

In a dictatorship like China, you can blame the top. In a democracy, in a republic, we have to blame [who we see in] the mirror.

The above conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Author: Alissa Wilkinson

Read More